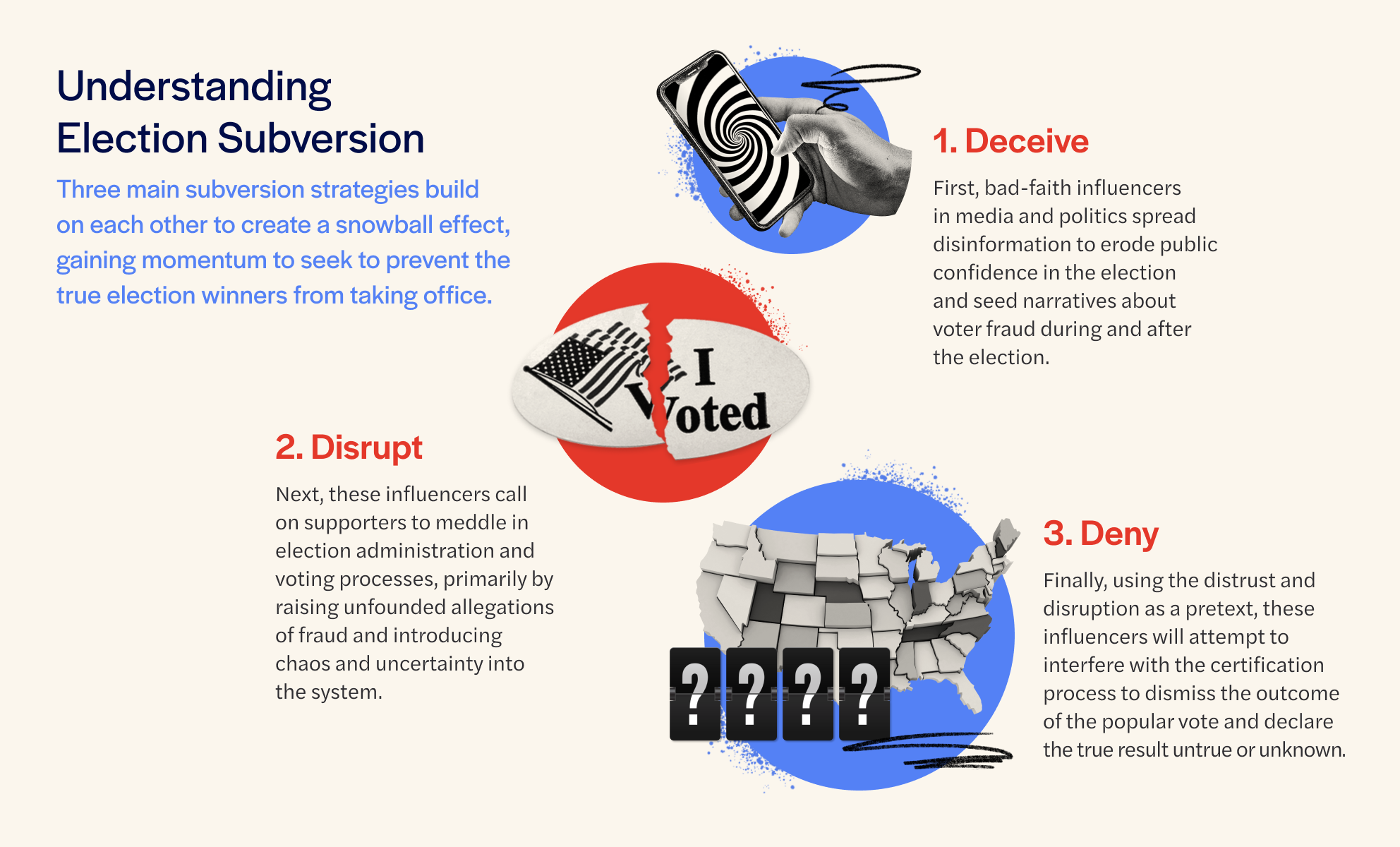

Deceive: First, bad-faith influencers, mainly in media and politics, spread disinformation to erode voter confidence in the election and seed narratives about voter fraud during and after the election.

In 2020, conspiracy theories about the “stolen election” prompted wide-ranging efforts to overturn or refuse to certify legitimate election results. This subversion campaign culminated in a mob attacking the United States Capitol, assaulting dozens of law enforcement officers, and testing the limits of our democracy. In 2024, we can anticipate that these tactics will escalate.

Our election experts have found that, for the past four years, bad-faith actors have continued efforts to push disinformation and “police” the election process. Their tactics are designed to deceive the electorate, disrupt the election, and ultimately deny any election results they do not like.

Read this analysis as a PDF Read this analysis as a PDF

The following outlines the most pressing election subversion strategies at the state and national levels and explains how to decode and defuse them.

The 2024 Election Subversion Strategy

The election denial movement is organized around the false idea that elections in the United States are rigged by shadowy, unseen forces. While the movement has ties to past conspiracy theories, the term “election denialism” rose to prominence after the 2020 presidential election, when Donald Trump refused to accept his defeat and instead made unsubstantiated claims that widespread fraud had led to a stolen election.

The politicians and organizations who reinforce election denialism today do so for political and financial gain. These bad-faith actors exploit the trust of their followers, convincing everyday Americans to spread their lies, interfere in election activities, and reject the truth. Whether true believers or political opportunists, their tactics pose a threat to our democracy.

The three main election subversion strategies build on each other to create a snowball effect, gaining momentum to prevent rightful election winners from taking office.

Disrupt: Second, these actors call on their supporters to meddle in the election administration and voting process to establish a pretext for disregarding the election outcome, primarily by raising unfounded false allegations of fraud and introducing chaos and uncertainty into the system.

Deny: Finally, referencing the distrust and disruption they have created, these actors will attempt to interfere or halt the certification process to disregard the outcome of the popular vote and declare the true result untrue, unknown, or unknowable.

These three steps represent a continuation of the election subversion strategies that have persisted since the 2020 election. As the general 2024 election season progresses, the strategy will likely be embraced with greater enthusiasm. Below is a breakdown of how this could continue to play out between now and January 2025.

Want more Democracy Insights?Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Step 1

Deceive

The election denialist movement is using several tactics to drive the narrative that elections are “rigged.” In the recent past, the notion that wins are being “stolen” has proven to be a powerful motivator, and in the 2024 election, we can see those narratives again taking various forms: namely, through mass challenges to the status of individual voters, disinformation about noncitizen voters, distortion of clerical or easily resolvable errors in election processes, and demands for the time-consuming hand-counting of ballots.

Filing mass challenges to the status of individual votersFiling mass challenges to the status of individual voters

To make it appear as though voter rolls are riddled with ineligible voters, organizations like True the Vote and the Election Integrity Network — creators and amplifiers of election denialist claims in 2020 — have orchestrated campaigns to have private citizens challenge thousands of voter registrations. These campaigns are enabled by flawed technology (EagleAI and IV3, to name a few), which use old voter files, unscrupulous methodologies, and other unspecified, untraceable sources to create lists of supposedly ineligible voters and present them as reliable data. These challenges are frivolous, redundant to ongoing work by election officials, and are an attempt to circumvent federal law.

Read more: Unraveling the Rise of Mass Voter Challenges →

Spreading disinformation about noncitizen votersSpreading disinformation about noncitizen voters

To position themselves to claim that the 2024 results will be skewed by ineligible votes, election conspiracy groups are promoting the false narrative that noncitizen immigrants are illegally casting ballots in presidential elections. Earlier this year, GOP Speaker of the House Mike Johnson elevated this narrative as a national issue with his press conference introducing the SAVE Act, which purported to make the act of non-citizen voting illegal. (In fact, it is already barred by the National Voter Registration Act.) The bill also would have required voters to produce burdensome documentary proof of citizenship to register to vote in federal elections, likely to disenfranchise voters. Johnson himself acknowledged there was no firm proof of a problem, yet asserted, “we all know, intuitively, that a lot of illegals are voting in federal elections.”

House Republicans later attached the bill to an emergency funding measure to keep the government open; Trump cheered the move and called on lawmakers to shut down the government if they could not win support for the noncitizen voting language. Trump posted disinformation about the issue on Truth Social: “THE DEMOCRATS ARE TRYING TO ‘STUFF’ VOTER REGISTRATIONS WITH ILLEGAL ALIENS. DON’T LET IT HAPPEN – CLOSE IT DOWN!!!”

Read more: Noncitizen voting lies, explained →

Read more: An illegal voter purge based on conspiracy theories →

Read more: Rebutting Allegations of Widespread Voter Fraud by Noncitizens →

Distorting good-faith errors or problems with election processesDistorting good-faith errors or problems with election processes

In the last presidential election, simple clerical and easily resolvable errors were played up by bad actors to promote the false notion of widespread fraud in the election.

For example, in 2022, using the wrong type of ballot paper in Maricopa County, Arizona resulted in some printed ballots that precinct tabulators could not read. This event was distorted and portrayed by losing candidates (including current Senate candidate Kari Lake) as a malicious effort to tilt the election. In 2023, the election research group Informing Democracy documented how a small programming error in a judicial race in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, “was turned into a widespread conspiracy in a matter of a few hours,” even though the error had been caught and remedied quickly.

Read more: Stephen Richer v. Kari Lake →

Promoting conspiracies to replace voting machines with unreliable hand countsPromoting conspiracies to replace voting machines with unreliable hand counts

As a means to cast doubt on election processes, election-denying groups often question the accuracy of electronic tabulator machines, demanding instead that jurisdictions count ballots by hand. The Georgia State Election Board recently indulged these questions and passed a measure to require precincts to hand-count all ballots (not all votes) before certification. One of these conspiracy-based pushes was successful in Nye County, Nevada, where, in 2022, county commissioners voted to require the hand counting of all paper ballots for the midterm elections. (The ACLU said the move had the makings of a “historic disaster” and resulted in counting at a “snail’s pace.”)

This election year, there’s more happening on this front in Nevada. In July 2024, activists called for a recount of two races in Washoe County, Nevada, and demanded they be done by hand. When the effort failed, they pressured county commissioners to refuse to certify the results because they claimed the machine-counted results were not trustworthy.

Read more: Hand-Counting Ballots Introduces Unnecessary Risks and Costs to Elections →

Step 2

Disrupt

Attempts to disrupt the election process can take many forms. Frivolous litigation and other requests can be filed to tie up the system, delay outcomes, and sanitize conspiracy theories. There may also be physical attempts to interfere in election administration and voting processes that are intimidating and chaotic. In 2020, attempts to manufacture “evidence” of impropriety using these disruptive tactics — through litigation, surveillance, and burdensome information requests — were used by the election-denying movement to create the impression that voters, election officials, and political candidates cheated. Although these tactics may wildly differ in approach and scope, they all have one common objective: to disrupt or otherwise cause chaos in the electoral process.

Filing litigation to challenge sound processesFiling litigation to challenge sound processes

This year, the Republican National Committee and aligned organizations have already filed nearly 100 lawsuits — primarily in battleground states — to challenge established election rules and procedures. The lawsuits have no merit, are often based on false claims or conspiracies, and were, for the most part, filed too late to remedy their purported complaint. They include challenges to voter roll maintenance practices in at least three states — Michigan, Nevada, and North Carolina — alleging that states aren’t doing enough to “clean” their rolls and remove ineligible voters. Others seek to give county officials some discretion over certification (a ministerial duty), challenge mail-in voting practices, and force election officials to conduct hand counts of ballots.

Read more: The lurking danger of zombie lawsuits →

Policing drop boxes and harassing votersPolicing drop boxes and harassing voters

Invoking the false narrative that the election process is untrustworthy — and disproven conspiracy theories regarding election fraud through drop boxes — bad-faith actors have encouraged citizens to be “watchdogs” in their states and local communities. Repeatedly, these so-called monitoring efforts have crossed the line into intimidation when the “monitors” have photographed voters, doxxed them, worn military-style tactical gear, or otherwise behaved in a threatening manner.

A chief proponent of these theories is True the Vote, a self-appointed vote monitoring operation that co-produced the debunked election-conspiracy film “2000 Mules,” which falsely alleged extensive “ballot harvesting” at drop boxes; the film has since been dropped by its distributor in response to litigation alleging the film constitutes defamation and unlawful voter intimidation. (See more accountability for True the Vote in Safeguards & Remedies below.) But the conspiracies have continued. During the 2022 midterms, a group affiliated with True the Vote announced a campaign to monitor dropboxes where voters deposit their ballots during early voting periods. People who were influenced by that campaign showed up in tactical gear outside drop boxes in Arizona, an intimidating sight. While that campaign was blocked by a court, we anticipate similar campaigns will arise.

Read more: League of Women Voters of Arizona v. Lions of Liberty →

Read more: Mark Andrews v. Dinesh D’Souza et al. →

Recruiting confrontational poll watchers and observersRecruiting confrontational poll watchers and observers

Under the false presumption that fraud is rampant and election officials are biased, some individuals are signing up to serve as poll watchers or observers as part of a national strategy to catch and expose preconceived notions of foul play. Since 2021, some states, including Texas, Florida, and North Carolina, have changed their laws to vaguely grant poll watchers “reasonable access” to ballots or entitle them to “effective” observation. Some of these laws also make it harder for election workers to remove disruptive poll observers.

Learn more: CSSE Chair Neal Kelley provides testimony to U.S. House Committee on Homeland Security →

Making unlawful threats to election officialsMaking unlawful threats to election officials

Baseless allegations of voter fraud and alleged election irregularities have sparked extensive harassment and threats of violence targeting election workers, officials, and their families. More than one-third of local election officials have experienced threats, harassment, or abuse due to their jobs in recent years. Because women largely make up this workforce, they are largely the target of these threats. A 2024 analysis by Scripps News Service found that 80% of election workers in the U.S. are women.

Read more: State and Local Solutions are Integral to Protect Election Officials and Democracy →

Abusing public records requestsAbusing public records requests

Since 2021, election offices have faced surging public records requests from election conspiracists seeking evidence to support their theories — with requests increasing as much as 700% since 2020. Responding to these requests has sometimes required offices to cut back voter outreach activities or repurpose a limited budget to hire new staff to deal with the requests. Further, many of the requests target specific employees and may be tied to harassment campaigns. Generative AI tools may make it easier to file even more requests in 2024.

Read more: How generative AI could make existing election threats even worse →

Step 3

Deny

The tactics described above to distort and disrupt the 2024 election are steps toward a radical goal: to deny certification of election results. The dishonest narratives and unfounded challenges will be misconstrued as “evidence” that the election was fraudulent and used to deny certification. This can happen in various ways: falsely claiming victory before final results are complete, pressuring officials to deny certification at the county level, filing frivolous legal challenges, and seeking unreliable audits, as well as interfering with the duties of members of the Electoral College or confirmation of presidential results at the joint session of Congress.

Making false claims of victoryMaking false claims of victory

Trump’s effort to overturn the election results arguably began on Election Night 2020, when he appeared in the White House at 2:30 a.m. to declare himself the winner and to criticize ongoing ballot counting as illegitimate. This was part of a strategy he telegraphed ahead of Election Day — likely because experts were predicting that he would appear to be ahead in the count on Election Night before many mail-in ballots were counted. While this false claim of victory had no legal significance, it was an immediate effort to shape the public narrative around the election results. Experts are again predicting that there may be no clear winner on Election Night — meaning that we are likely to see similar false claims of victory before all the votes have been counted.

Read more: The ‘blue shift’ and ‘red mirage’ in election results, explained →

Refusing to certify at the county levelRefusing to certify at the county level

In 2020, Trump’s effort to overturn the election results included a pressure campaign directed at local officials in Michigan charged with certifying election results at the county level. Since then, county officials across the country (including in key swing states like Arizona, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Nevada) have threatened or refused to certify election results, citing conspiracy theories about election fraud. While these efforts have all ultimately failed, refusals to certify are disruptions that can delay the election process, and by doing so, further fuel distrust in the process and outcome.

Read more: Election Certification is Not Optional →

Devising frivolous challenges and unreliable “audits”Devising frivolous challenges and unreliable “audits”

If a losing candidate refuses to accept the results, they can fuel distrust and delay their defeat through drawn-out unreliable “audits” or by challenging the outcome in court. To this end, former president Trump and his allies filed more than 60 cases challenging the results of the 2020 election.

Even after Joe Biden was inaugurated as president, conspiracy theorists continued to question the outcome and demand investigations. In spring 2021, the Republican caucus of the Arizona state senate hired a small Florida-based firm with ties to the election denier movement and no election auditing experience — called the Cyber Ninjas — to conduct an unreliable audit that lasted months, cost nearly $9 million, and uncovered no evidence of fraud. Copycat “audits” popped up across the country.

In 2022, other candidates who lost their elections followed Trump’s example by refusing to accept defeat. 2022 Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake and attorney general candidate Abe Hamadeh have continued to pursue challenges for nearly two years after their losses, while campaigning as candidates for the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives, respectively, in 2024. None of these cases or investigations has produced evidence that the election results were wrongly decided.

Read more: Partisan Election Review Efforts in Five States →

Interfering with the Electoral College processInterfering with the Electoral College process

County certification delays or court intervention based on unfounded claims of fraud could have serious ripple effects for the 2024 election. Under the Electoral Count Reform Act, each state must certify its electoral college slate by December 11, 2024, and electors meet to cast their ballots on December 17, 2024. Delays due to disinformation or disruption could prevent a state from meeting those deadlines, which could lead to uncertainty, disenfranchisement, or unrest.

Read more: Understanding the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022 →

Pressuring Congress to objectPressuring Congress to object

In the run-up to January 6, 2021, President Trump and his supporters engaged in a behind-the-scenes pressure campaign to convince Vice President Mike Pence to stop, delay, or rig the certification vote, although Pence rightly insisted he had no authority to do so. As Pence has emphasized, “Frankly, there is no idea more un-American than the notion that any one person could choose the American president.”

But many others acquiesced to these requests. When Congress met on January 6, several Republican lawmakers forced a vote on objections, based on conspiracy theories, to Arizona’s and Pennsylvania’s slates of electoral votes. The violent insurrection interrupted a debate about the objections, but later that night, when Congress reconvened, 147 members voted to reject one or both slates.