Proportional representation and the future of the center-right

- September 12, 2023

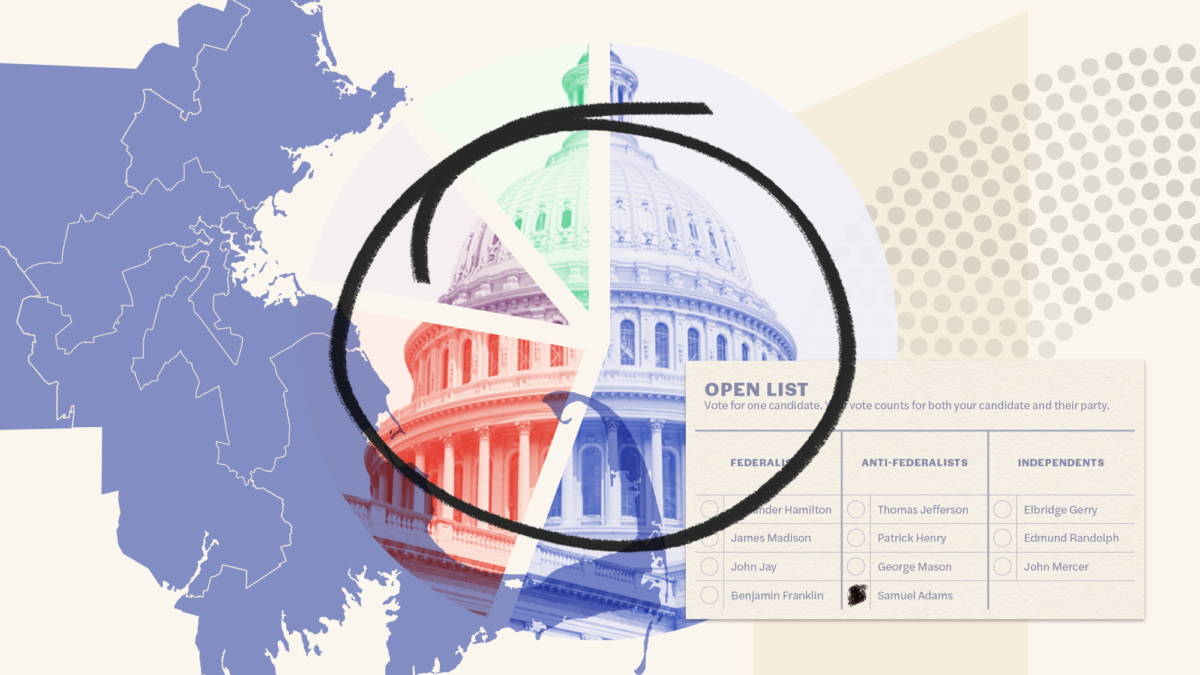

Center-right, socially moderate, and fiscally conservative Republicans are the voters and politicians who perhaps suffer most in our current hyper-polarized, two-party doom loop, to use Lee Drutman’s apt term. We (and I am one such voter) have been sentenced to languish within the doom loop under the power of Duverger’s law. As close to a universal law as we get in political science, it holds that an election system combining single-member districts with first-past-the-post voting in which a candidate can win with a mere plurality results in a two-party system.

Duverger’s law thus presents moderate, center-right Republicans with an egregious choice. On the one hand, we can stay loyal to a MAGAfied GOP, one that includes way too many hard-right ideologues, many of whom are in thrall to a shameless demagogue. On the other hand, we can exit the GOP, either going into political no man’s land or joining a Democratic Party lurching to the left, away from our core dispositions and beliefs. Is there a third option, one that would give us an actual voice?

We would likely have such an option in an electoral system that provided for proportional representation (PR) in the House of Representatives. Indeed, the already sizable faction of moderate, center-right lawmakers in the House, and the portion of the electorate whom they represent, would benefit the most from PR. In such a system, we could expect more than two parties to emerge, including one representing our segment of the polity.

From the vantage point of the polity overall, the emergence of a moderate, center-right party would produce much of the upside that PR advocates anticipate. Such a party would provide a reliable yet flexible fulcrum for responsive policymaking, moderate our politics, and thus help shore up our beleaguered republic. Though the new center-right party will at times work against progressive and liberal policy agendas, those on the left will ultimately benefit from this political development. Indeed, the fate of democracy in America may depend on it.

Moderates and their representatives

I know that to suggest our collective fate may lie in the hands of centrist Republicans is a counterintuitive proposition. To begin to justify it, let’s understand the portion of the electorate that would determine the size and outlook of a moderate, center-right party in the House. How big is this group of voters, and what do they believe? Given the uncertainty inherent in this exercise, we should triangulate across different data sources.

In its landmark “Hidden Tribes” survey report from 2018, More in Common, a nonprofit that studies polarization and ways to overcome it, identified a segment of “Moderates” comprising 15 percent of the U.S. population. Moderates tend to be “engaged in their communities, well informed, and civic-minded.” They also “shy away from extremism of any sort.” Like other segments in what More in Common calls the “exhausted majority,” Moderates often feel overlooked in politics. They are fed up with polarization. They believe in pragmatism and the search for common ground. These viewpoints distinguish Moderates from the more ideological and populist conservatives further to the right in More in Common’s segmentation.

In 2021, Drutman of New America used a nearly 5,000-respondent survey by the Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group to project what the U.S. party system could look like under PR. Drutman’s analysis projected six parties emerging in the hypothetical PR electorate, one of which roughly corresponds with More in Common’s Moderates. Drutman labeled his variant the Growth and Opportunity Party. It comprises 14 percent of this particular modeled electorate and in effect represents “the socially moderate, pro-business wing” of the current GOP. The Growth and Opportunity Party voters differ demographically in a few key respects from those of the other two Republican offshoots that emerge in Drutman’s model, a Christian Conservative Party and a Patriot Party. They are less apt to profess being “born again,” and they include a greater proportion of Hispanics.

Who would represent the voters identified by More in Common and Drutman in a PR system? What outlooks, policy preferences, and political styles would they bring to the House? With the caveat that we are still extrapolating, we can already discern some of these attributes among the two “families” of lawmakers on the moderate side of the current House majority. These include the Republican Governance Group (formerly the Tuesday Group) and GOP members of the Problem Solvers Caucus. They are led by Representatives David Joyce of Ohio and Brian Fitzpatrick of Pennsylvania, respectively.

These leaders and many of the members of their caucuses are routinely determined by the objective assessments of the Lugar Center to be among the most bipartisan members of the House. Further afield, over in the Senate, Susan Collins, Lisa Murkowski, and Mitt Romney would likewise fit in well in the new party. Outside of Washington, Charlie Baker and Larry Hogan, recent two-term GOP governors in the blue states of Massachusetts and Maryland, would be exemplary leaders.

Before turning to the potential dynamics and impact produced by a moderate, center-right party operating in a PR-elected House, we should flag one reality. These effects will not primarily result from an increase in the proportion of seats held by lawmakers with this disposition. Conservatively assuming that, based on the above surveys, 10-15 percent of the electorate would support such a party, their legislative representatives should expect a similar proportion of seats under PR. A recent Washington Post analysis indicates that there are presently 49 GOP representatives who belong to the Problem Solvers Caucus and/or the Republican Governance Group. The moderate, center-right factional elements thus already hold 11 percent of the seats in the House’s current 435-seat configuration. A PR system that fairly translates votes into seats will not produce a large and disproportionate increase in their ranks.

Liberating the lawmakers

So if it wouldn’t substantially increase their numbers, what would PR do for these moderate, center-right legislators? It would free them from the polarizing, hyperpartisan influences of (a) teamsmanship in Congress and (b) primary voters in single-member, winner-take-all districts.

Princeton University’s Frances Lee has highlighted the problems associated with legislative “teamsmanship.” Under the sway of teamsmanship, lawmakers go out of their way to side with their co-partisans, even on nonideological matters that do not reflect their own substantive views or priorities, in order to bolster their collective prospects in the next election. Consider the so-called Hastert rule, under which GOP speakers refuse to bring bills to the floor without the support of a majority of their caucus, even if they could pass with Democratic votes. This informal “rule” is a powerful enforcement mechanism for teamsmanship. Insofar as moderate, center-right lawmakers are the ones best positioned and most disposed to find common cause with colleagues across the aisle, they bear the brunt of its use.

With the thin and insecure majorities of recent decades, where partisan control of the House is up for grabs in most elections, the sway of teamsmanship only increases. It weighs especially heavily on center-right moderates. They increase their risks of getting primaried by irate Republican donors and activists whenever they fail to toe the party line. The power of these zealous gatekeepers is magnified when you combine the rampant geographic sorting and partisan gerrymandering of the electorate with our single-member-district, first-past-the-post elections. In such a system, winning the primary is tantamount to winning the election. When moderate, center-right Republicans ruffle the feathers of the GOP ideologues, they risk facing a well-funded and more doctrinaire GOP opponent in the primary election. This is one of the reasons, for example, that many of these representatives have either silently looked away from recent attacks on our democratic values and institutions by their co-partisans, or have argued that “both sides” were to blame.

As the research of political scientists Andrew Hall of Stanford University and Danielle Thomsen of the University of California, Irvine has demonstrated, the net effect of all these forces is a steady decline in the number of moderates serving in Congress. In a PR-based House of Representatives, however, members of the moderate, center-right party would have these burdens and constraints lifted. They would no longer have to subordinate their legislative agendas and pragmatic, problem-solving politics to stay allied with ideologues and bomb-throwers to their right. They would form their own team with like-minded lawmakers. In turn, they could join with other emerging parties to form new coalitions depending on the issues at hand. Drutman’s hypothetical party system, for example, identifies a center-left American Labor Party that would provide moderate, center-right lawmakers with an aligned partner on many social issues, and a center-left New Liberal Party that could play a similar role on fiscal and economic policy. Far from putting their electoral prospects in jeopardy, moderate, center-right representatives’ preferred modes of policymaking and representation would be expected and rewarded by the voters who control their fates.

A sturdy yet flexible fulcrum

In a House with, say, four to six distinct parties, the moderate, center-right party would occupy the strategic high ground. Given its position in the chamber and pragmatic mode of operating, it would be in great demand as a coalition partner. This would be true when the House is being organized and the speaker elected at the start of each Congress, on recurring procedural matters, and in building majorities for specific policies.

Through the coalitional dynamics born of center-right moderates’ liberation, we could anticipate more balanced, responsive, and stable policymaking that better reflects public opinion. We would see far fewer extreme, binary choices and messaging votes meant to put members of the other party in an awkward position. We could also expect, for example, any abortion policy made in a PR-based House to represent the public’s preferences for it to be safe and legal in most (though not all) circumstances. Immigration policy would stand a better chance of moving forward and be more apt to combine more systematic enforcement with improved access to citizenship. Spending cuts would be more likely to be blended with “revenue enhancements” to move toward a balanced budget. Debt ceiling showdowns would be a thing of the past.

In addition, we could expect to see more variation and shifting in policy coalitions, driven in large part by the pragmatism of the center-right party. Its members might work, for example, with left-of-center partners to rein in qualified immunity abuses or pass sensible gun control measures. But they would also be prepared to work with right-of-center colleagues to pursue an ambitious, all-of-the-above energy policy or reduce excessive and growth-stifling licensing requirements. With the advent of shifting coalitions in the House, we would see less gridlock and more legislating.

In sum, the moderate, center-right party would serve as a sturdy yet flexible fulcrum for responsive policymaking. It would put the House, and Congress as a whole, back in the business of tackling the most pressing problems facing the nation. As Philip Wallach of the American Enterprise Institute has recently and powerfully reminded us, this is the basic purpose of Congress: No other institution in our system of government can amply represent and reconcile our differences.

With Congress working more effectively to help the American people hash out our myriad disagreements, many of us will begin to feel less alienated from our national government. And if demagogues or other malign domestic actors once again threaten U.S. democracy, under PR, members of the moderate, center-right party would be ready, willing, and able to oppose them. Rather than turning on their representatives for standing up to transgressors and extremists, the new sets of voters who control their fates will expect nothing less.

Ripple effects and building the party

We’ve focused thus far on dynamics within the House, but let’s pull the lens back to consider possible ripple effects in other parts of our political system. Some spillover to the Senate seems likely, even though electoral arrangements for that body cannot be converted to PR. Yet, as members of the moderate, center-right party distinguish themselves as effective lawmakers and problem solvers in the House, we could expect many of them to move on to the Senate. Given the expectations of their constituents and how they will have learned to operate in a PR-based House, they would likely work in similar ways there.

With the need for an Electoral College majority to win the presidency, it would be difficult for leaders of a party representing just 10-15 percent of the electorate to win that office. But it would also be difficult for any right-of-center candidates to win without the endorsement of the moderate party closest to them. Vice-presidential candidates drawn from this party would also be good ticket balancers for candidates on the right and left alike. So at the margins, over time, PR in the House could ease the polarizing aspects of presidential politics.

Contemplating the effects in the states further stretches the bounds of speculation. In blue states, center-right moderates who have distinguished themselves in the House would have solid platforms on which to run for governor. In red states, this partisan permutation may not be able to carry the day, but it may serve to produce more moderate choices for gubernatorial candidates than otherwise would emerge.

We should also note some critical infrastructure that will be necessary to support a moderate, center-right party in a House of Representatives elected via PR. This would include state party organizations capable of developing candidate pipelines, fundraising systems, messaging operations, and on-the-ground organizers and mobilizers. It will be no small thing to build, sustain, and align those party organizations across the states.

There would also be a need for a steady supply of innovative policy ideas for these pragmatic problem solvers to apply. The polarization of think tanks has eroded the number of institutions prepared to meet this requirement. However, there are a few stellar institutions, like the Niskanen Center, the R Street Institute, and the Rainey Center, that are in a position to help. More will be needed.

Beyond policy ideas, members of the moderate, center-right party in the House will need assistance from think tankers and democracy advocates in clarifying and explaining the politics of moderation to their voters and the American public. This will be a challenge because Americans have gotten used to understanding politics and government via stark ideological cues; but it is nonetheless imperative. Because, as Aurelian Craiutu of Indiana University and the Niskanen Center has observed in a passage that is fitting to conclude with: “Moderation appears as an essential ingredient in the functioning of all open societies because it acts as a buffer against extremism and promotes a civil form of politics indispensable to the smooth running of democratic institutions.”

This piece originally appeared in For A Better Democracy: Proportional Representation, a symposium published by Democracy Journal in partnership with Protect Democracy and with support from Democracy Fund.

Related Content

It can happen here.

We can stop it.

Defeating authoritarianism is going to take all of us. Everyone and every institution has a role to play. Together, we can protect democracy.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy