Cyrena Kokolis supports Protect Democracy’s efforts to create a more representative, responsive, and resilient democracy through electoral reform advocacy and litigation.

Fusion voting, explained

- December 19, 2023

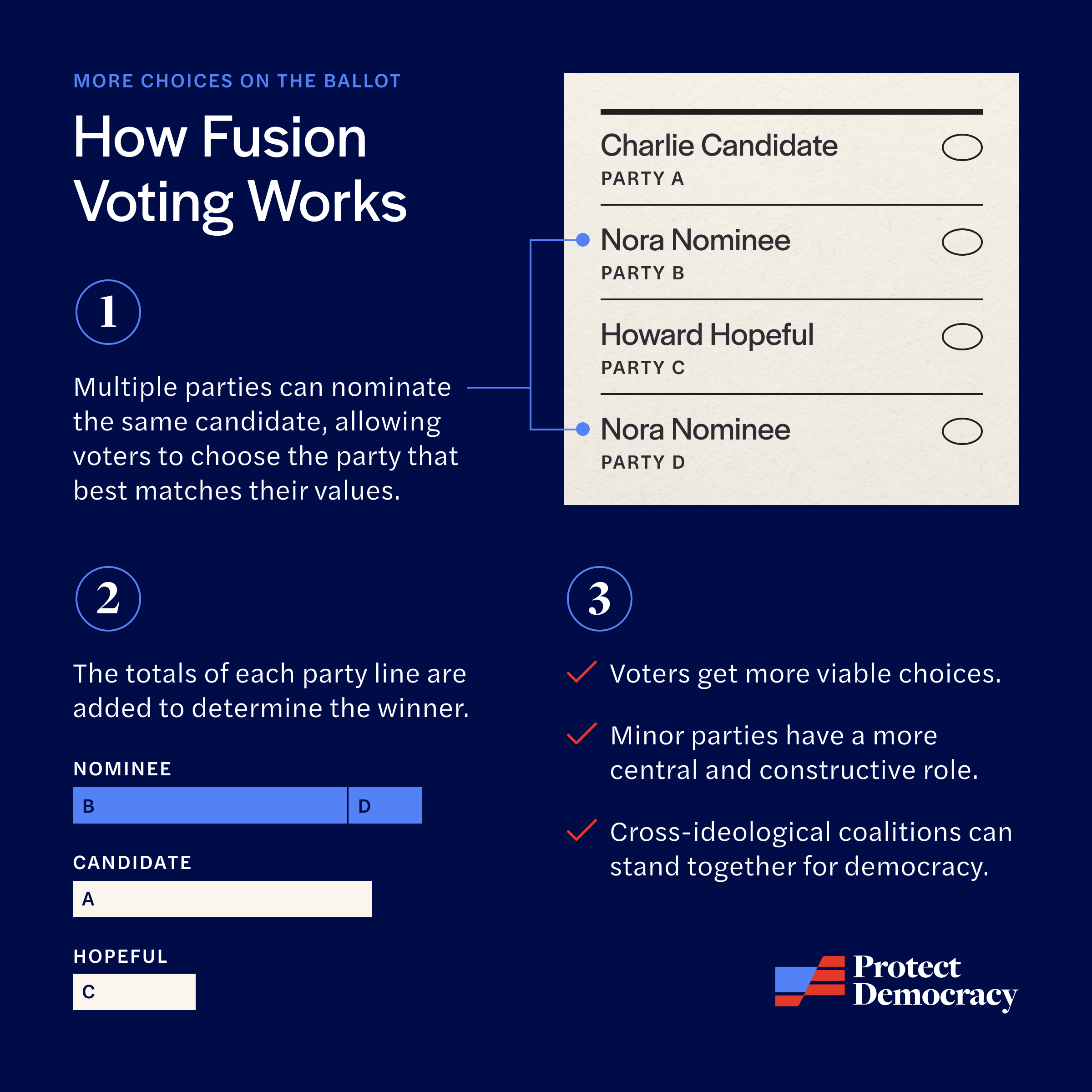

Fusion voting refers to a process that was once universal throughout the U.S. and still features prominently in several states: more than one political party nominates the same candidate on the ballot, allowing voters to support their preferred candidate — without having to support one of the two major parties. Typically, this means a minor party and major party “fuse” together to cross-nominate and support the same candidate. A candidate’s vote total is the sum of the votes they received on each of their nominating party’s lines.

Read our December 2023 report

Fusion Voting and a Revitalized Role for Minor Parties in Presidential Elections

Potential benefits of fusion voting

Experts increasingly agree that the current structure of U.S. elections is aggravating some of the most pressing problems undermining our democracy, including political extremism, hyper-polarization, lack of competition, and the absence of constructive opportunities for minor political parties. That is why more than 120 leading democracy scholars have encouraged states to re-legalize fusion voting, which could alleviate these concerns by:

In competitive races today, voting for a minor party can feel futile or worse — by helping elect someone’s least favored candidate. Some voters might accept this tradeoff to bring attention to the minor party’s priorities, but with fusion, voters don’t have to make this sacrifice. Fusion voting allows a minor party to elevate their policy agenda without the downside risk, offering their ballot line to the competitive candidate willing to advocate for their priorities. Because election results reveal the support a candidate earns from each nominating party’s ballot line, a minor party that delivers a meaningful share of the vote total can encourage a candidate to support its policy goals. Greater visibility into the ideological diversity throughout the electorate could, in turn, allow groups marginalized under current rules to exert more power in the political process.

Despite widespread frustration with the two major parties, voters today are nonetheless required to support one of them to cast their ballot for a competitive candidate. When candidates can compete for and earn multiple nominations, voters are freed from this binary, and can instead cast a meaningful vote on the ballot line of a minor party more aligned with their political worldview. With the option to select from more than one nominating party, voters have a greater choice of policy platforms and priorities. This could be particularly meaningful for voters in the political center who want to support moderate candidates committed to democracy and the rule of law, but are concerned about some positions of the nominating major party.

Allowing minor parties to play a more prominent and additive role could improve our two-party system and better reflect the electorate’s ideological diversity. This modest change could reduce the degree to which political conflict is perceived as a zero-sum, existential battle between two hegemonic groups. And even modestly reducing cross-partisan hatred (known as “affective polarization”) could have a host of benefits, such as making it easier for moderate officials to temper extremism on their own side. Fusion could also serve as a bridge to a more proportional system of representation, where the number of votes a party receives would lead to corresponding number of seats they win. Experts assert that moving beyond just two competitive parties in the U.S. could allow for a more fluid and responsive political system, as well as better and more representative governance.

An authoritarian movement lacking majority support in the electorate can nonetheless win at the ballot box when the pro-democracy majority splinters. Building and sustaining an ideologically diverse electoral coalition is always difficult, but fusion can make it easier by empowering factions with differing views on policy but a shared commitment to liberal democracy to unify in support of a single candidate — while separate ballot lines allow them to preserve their distinctive identities and priorities.

“Legalizing fusion would . . . empower the individual voter, especially one frustrated with our two major parties. A vote for a candidate on a centrist party’s line would be a powerful and effective way to signal that you favor problem-solving over posturing and to reward politicians who are workhorses instead of grandstanders.”

Former Gov. Christine Todd Whitman (R-NJ) & Former Sen. Robert Torricelli (D-NJ)

Fusion voting has a long tradition in the United States

Until the turn of the 20th century, parties nominated their preferred candidates without restriction, and candidates routinely earned multiple nominations. Minor parties used cross-nominations to elevate neglected issues into the political mainstream and build cross-ideological alliances to advance their goals. In the mid-1800s, abolitionist minor parties ascended from obscurity to become political heavyweights as they used cross-nominations to elect anti-slavery Whigs and Democrats, eventually joining forces to form the first major party forcefully opposed to slavery: the GOP. In the run-up to the Progressive Era, minor parties representing working class interests reshaped the political landscape by cross-nominating Democratic and Republican candidates who were willing to advance their priorities.

State legislatures around the country then passed new laws prohibiting fusion voting to reduce minor party influence and competition. These restrictions are widely viewed as unconstitutional, impermissibly burdening fundamental rights to political association and participation. Indeed, New York’s high court struck down the state’s anti-fusion laws in the early 1900s, and fusion voting has continued to play a prominent role in federal, state, and local elections in the Empire State. Cross-nominations are common in Connecticut as well, while continued enforcement of anti-fusion laws in most other states have relegated minor parties to the electoral periphery.

Challenging anti-fusion laws in courtChallenging anti-fusion laws in court

Anti-fusion laws place a severe burden on the fundamental political rights of voters, candidates, and minor parties. As a result, such restrictions have been of questionable constitutionality since they were first proposed and adopted at the turn of the 20th century. There is growing recognition that in many states these laws clearly violate the robust political rights guaranteed under state constitutions.

Moderate political parties in New Jersey and Kansas are currently challenging the constitutionality of their states’ anti-fusion restrictions in court. In both states, our organization represents voters concerned about hyper-polarization and political extremism who want to vote for moderate candidates on a moderate party’s ballot line.

“[A]ntifusion laws should trigger exacting judicial scrutiny. . . [T]hey are self-conscious devices that go above and beyond the advantages directly accruing to the two parties by virtue of the single-member geographical district. Antifusion laws further entrench the two dominant parties by dramatically raising additional barriers to competition.”

Samuel Issacharoff & Richard Pildes, “Politics As Markets: Partisan Lockups of the Democratic Process”

FAQs

Further reading

Related Content

It can happen here.

We can stop it.

Defeating authoritarianism is going to take all of us. Everyone and every institution has a role to play. Together, we can protect democracy.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy