How Did We Get Here: Primaries, Polarization, and Party Control

- October 12, 2023

From More than Red and Blue: Political Parties and American Democracy

Abstract

We examine the existing evidence on party primaries and political polarization in American politics and find that the existence or openness of primary elections is not strongly related to polarization. Rather, primaries have led to other potentially more serious problems in American politics — a loss of control of parties by their leaders, the increased nomination of inexperienced politicians uninterested in policymaking, and the potential for significant democratic erosion. We conclude with some discussion about ways to re-empower parties to select capable nominees.

Primaries and PolarizationPrimaries and Polarization

In June of 2022, Colorado saw competitive Republican primary elections in three key statewide races: Governor, U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State. In each of those races, a fairly conventional Republican candidate faced off against a more conservative, Trump-embracing, election-denying alternative who was favored by hardcore activists.Yet on election day, all three conventional candidates won, leaving their party in a better position to take on Democratic incumbents in the fall election.1These efforts would nonetheless prove unsuccessful, with Democrats winning all three races.

This story is not consistent with the conventional wisdom on primary elections, which generally hold that primaries are responsible for the ongoing polarization of the parties. As we discuss in this essay, neither the existence of primaries nor their rules play a particularly large role in the parties’ ideological polarization. However, primaries do present some very real and growing challenges to party leadership, making it more difficult for leaders to manage parties in responsible ways and make decisions that benefit both them and the country at large. Party nominations, we argue, are in need of significant reform — not so much to advantage the nomination of moderate candidates, but to advantage the nomination of candidates who will protect and advocate for democracy.

The idea that primaries are largely responsible for polarization has a long history. The usual described mechanism is that the people who participate in primaries are more ideologically extreme than the people who participate in the general election. None other than V.O. Key2Key, Valdimer Orlando. 1956. American State Politics: An Introduction. New York: Knopf. raised this concern as early as 1956, suggesting that “in states with a modicum of interparty competition primary participants are often by no means representative of the party.” Ranney3Ranney, Austin. 1968. “The Representativeness of Primary Electorates.” Midwest Journal of Political Science, 12 (2), 224-238. however, found little evidence that primary and general electorates were meaningfully different. More recently, Sides et alia4Sides, John, Christopher Tausanovitch, Lynn Vavreck, and Christopher Warshaw. 2020. “On the Representativeness of Primary Electorates.” British Journal of Political Science, 50 (2), 677-685. used primary election administrative records and multi-year surveys to examine demographic and policy differences between primary electorates and general electorates. Essentially, they found no differences; Republicans and Democrats who participate in primaries look very much like the Republicans and Democrats participate in general elections. This is consistent with findings by Hirano et alia5Hirano, Shigeo, James M. Snyder Jr., Stephen Daniel Ansolabehere, and John Mark Hansen. 2010. “Primary Elections and Partisan Polarization in the US Congress.” Quarterly Journal of Political Science 5 (2): 169-191. that neither the existence of nor the level of turnout in primary elections appear to be related to polarization.

To be sure, there are notable differences in primary and general electorates, and, unlike in primaries, there is some incentive for general election candidates to reach out to unaffiliated voters and even some more moderate voters in the other party. As Mann6Mann, Thomas E. 2007. “Polarizing the House of Representatives: How Much Does Gerrymandering Matter?” in Nivola, Pietro S. and David W. Brady, eds., Red and Blue Nation. Brookings: 263-283. argues, there may be an important interaction between primary elections and gerrymandering that induces polarization even if neither on their own is much of a contributor, but there is little reason to think that the primary electorate is any more ideologically extreme than any other group that might select a party’s nominees, including convention delegates, caucus goers, or party bosses.

Moreover, any differences between primary and general electorates do not seem to vary by how open or closed the primary system is. McGhee et alia7McGhee, Eric, Seth Masket, Boris Shor, Steven Rogers, and Nolan McCarty. 2014. “A Primary Cause of Partisanship? Nomination Systems and Legislator Ideology.” American Journal of Political Science 58 (2): 337-351. examined this systematically using roll call vote-based ideal points of legislators across all 99 state legislatures and finding that the rules governing primary participation are unrelated to legislator extremism. This finding was echoed in Sides et alia.8Sides, John, Christopher Tausanovitch, Lynn Vavreck, and Christopher Warshaw. 2020. “On the Representativeness of Primary Electorates.” British Journal of Political Science, 50 (2), 677-685.

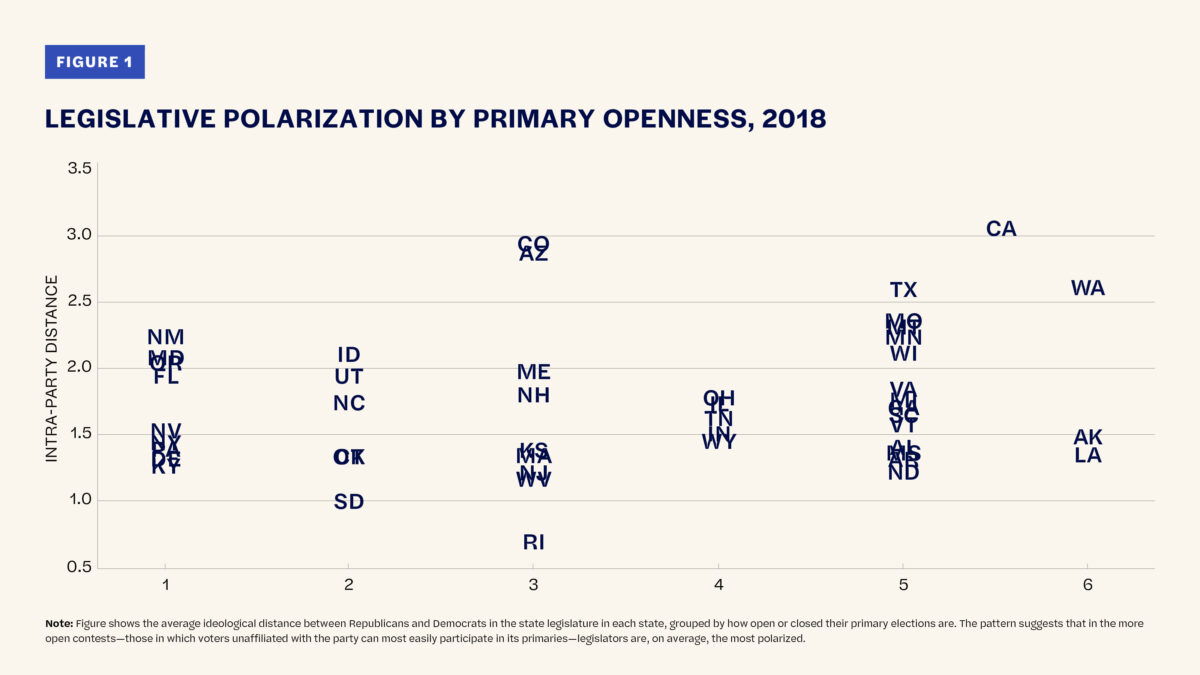

For a somewhat simplified look at this, Figure 1 charts all fifty states in terms of the openness of their primary system.9National Conference of State Legislatures. 2021. “State Primary Election Types.” NCSL. January 5. https://www.ncsl.org/elections-and-campaigns/state-primary-election-types. These data are from 2018, the most recent available. We have ordered the states from most restrictive (closed primary) to the least restrictive (the top-two runoff systems in California, Louisiana, and Washington). The vertical axis is a measure of legislative polarization — the difference between the mean Republican legislator ideal point (their left-right ideological position as revealed by their voting behavior on roll call votes) and the mean Democratic legislator ideal point in each state.10Shor, Boris. 2020. “Measuring America’s Legislatures.” Dataset. https://americanlegislatures.wordpress.com. Accessed July 7, 2022. In theory, if more closed primaries restrict participation to the most ideologically extreme voters, we should see the more polarized chambers toward the left side of the figure. In fact, there is little relationship at all, and actually trends somewhat in the opposite direction.

Why this is the case is not immediately obvious. One possibility is that, as Norrander and Wendland11Norrander, Barbara, and Jay Wendland. 2016. “Open Versus Closed Primaries and the Ideological Composition of Presidential Primary Electorates.” Electoral Studies 42 (June): 229-236. find, prospective primary voters behave strategically and react to changes in party registration rules. That is, if a party primary closes its doors to independent voters, independents who lean toward that party may change their registration so that they can participate, whereas such leaners may remain independent in other states where rules permit them to vote in the primary. It may also be that party elites are capable of steering primary election results toward their preferred candidates regardless of the composition of the primary electorate.

We can also think of this issue in a relatively broad historical sense. According to studies of congressional roll call voting, one of the most polarized periods in the history of the U.S. Congress (prior to today) was the late 19th and early 20th centuries.12Voteview. 2016. “The Polarization of Congressional Parties.” Voteview. January 30. https://legacy.voteview.com/political_polarization_2015.htm. This occurred prior to the introduction of primary elections; the bulk of congressional nominations at that time were made by party leaders and conventions. Most states adopted primaries for their congressional nominations in the first few decades of the 20th century. Yet one of the least polarized periods in congressional history was in the 1950s and 60s, when primaries were widely in effect. This hardly directly disproves the influence of primaries, but it certainly doesn’t suggest much of a polarizing role for them.

The Loss of Party ControlThe Loss of Party Control

Primary elections may not be responsible for polarization, but that hardly lets them off the hook for other problems with democracy. They create other significant challenges for a democracy — specifically, the loss of control of the party by its leaders.

In one sense, it seems odd that the party bosses of the early 20th century would cede control of nominations to rank-and-file party members. How did those powerful party leaders lose that fight? Alan Ware13Ware, Alan. 2002. The American Direct Primary: Party Institutionalization and Transformation in the North. Cambridge University Press. helps solve this mystery by noting that party politics of that era was becoming more challenging for party leaders. The rise in the number of candidates and occasional factional splits within local parties sometimes meant that more than one candidate would claim to be the party’s legitimate nominee. Creating primary elections, run and regulated by state governments, added the state’s imprimatur to a party nominee, preventing dangerous party splits in general elections. Party leaders at that time assumed that they would still be able to control nominations even though primary voters were technically in charge. After all, party voters still did not know very much about the candidates and were dependent upon party leaders to help them distinguish between the loyal partisan candidates and the pretenders.

In a multi-party democracy, politicians, activists, and voters can leave a party if they are dissatisfied with it and join or even create another… This is close to impossible in the United States

This theory would be further put to the test in the 1970s, when primaries were suddenly applied in large numbers to the presidential nomination process. Prior to that decade, presidential nominees were selected by party leaders at party conventions, often huddled in smoke-filled rooms and sometimes drawing on information learned in high-profile primary elections.14The West Virginia Democratic primary of 1960 didn’t really assign many delegates one way or another, but it was a chance forthe Catholic John Kennedy to demonstrate his electioneering skills and his multi-sectarian appeal to a highly Protestant state while defeating popular party figure Hubert Humphrey. The 1968 Democratic nomination cycle, however, was a mess. It saw the assassination of the popular Robert Kennedy, who had been dominating primary contests, a divisive and bloody summer party convention in Chicago, and that convention’s nomination of Humphrey, despite his having participated in no primaries. His narrow loss in the general election to Richard Nixon, a candidate many Democrats had seen as beatable, left Democrats in a nomination crisis. Many longstanding Democrats feared the party could not pick winning candidates anymore, and newer party activists and voters had come to believe that convention delegates no longer reflected their wishes. The party’s McGovern-Fraser Commission would embrace primaries as just one way to make convention delegations more representative of lay party members, but it ended up radically transforming presidential nominations.

Following the party’s reforms between 1969 and 1972, state primaries suddenly became highly consequential for presidential nominations. As entrepreneurial candidates like George McGovern and Jimmy Carter deduced, it was possible to win the nomination by doing well in early contests like the Iowa Caucuses and the New Hampshire Primary, even if party leaders were not very fond of them.15Polsby, Nelson W. 1983. Consequences of Party Reform. Oxford University Press. As Cohen et alia16Cohen, Marty, David Karol, Hans Noel, and John Zaller. 2008. The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform. University of Chicago Press. describe, however, party leaders managed to reassert their control over the presidential nomination process starting in 1980. They did so largely through the endorsement process. By coordinating behind a candidate publicly, they could signal to party voters just who the proper nominee should be, and, importantly, party voters tended to ratify their choices for the next few decades.

Yet this system began to fray in the new century. Howard Dean had a surprisingly strong showing in 2004 despite many party leaders disliking him, and Barack Obama won his party’s nomination four years later even though the bulk of endorsers prior to the Iowa Caucuses were leaning toward Hillary Clinton. But if those were cracks in the party’s armor, the 2016 Republican nomination process was a complete shattering of it. Party leaders in that cycle overwhelmingly signaled a strong distaste for Donald Trump yet failed to converge behind an alternative candidate, and Trump managed to dominate the primaries and caucuses by parlaying his money and fame. By contrast, Democratic leaders in 2016 quickly and strongly converged on Hillary Clinton, who won the nomination, but only after a surprisingly strong and lengthy rivalry with Bernie Sanders despite his lack of party backing. The 2020 Democratic cycle offered reasonable evidence of a Democratic Party that had made a choice — if somewhat late in the process — and got voters to go along with it17Masket, Seth. 2020. Learning From Loss: The Democrats 2016-2020. Cambridge University Press., but populist movements and factionalism continue to undermine the choices of party leaders.

We should note here that primaries are a defining aspect of America’s party system. While a number of other democracies use primaries, especially in Latin America and increasingly in a few European states, none have played such a long and influential role in party governance as they have in the United States. In part, this is related to the U.S.’s persistent two-party system, as Taylor et alia18Taylor, Steven L., Matthew S. Shugart, Arend Lijphart, and Bernard Grofman. 2013. A Different Democracy. Yale University Press. articulate. In a multi- party democracy, politicians, activists, and voters can leave a party if they are dissatisfied with it and join or even create another that is still reasonably close to their policy goals. This is close to impossible in the United States, where the diametrically opposed party is the only option. Instead, the way to participate meaningfully if one is dissatisfied with their party is to change it, which can be done by championing new candidates in the primary or running oneself. The relative porousness of American political parties and primary elections make this possible whereas changing a party from an entry level is far more daunting in most other democracies.

The Consequences of Primary ControlThe Consequences of Primary Control

Party trends in the twenty-first century suggest that leaders of both parties struggle with nominations. Parties are increasingly nominating candidates with little experience in politics19Porter, Rachel A., and Sarah Treul. 2020. “Reevaluating Experience in Congressional Primary Elections.” Working paper. April 17., undermining the functionality of government and prioritizing posturing over legislating. This trend has been sharper among Republicans20La Raja, Raymond, and Jonathan Rauch. 2020. “How Inexperienced Candidates and Primary Challenges are Making Republicans the Protest Party.” Brookings. June 29. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/fixgov/2020/06/29/how- inexperienced-candidates-and-primary-challenges-are-making-republicans-the-protest-party/, but both parties have found the experience necessary for governing and coalition-building to be in shorter supply in recent years. One-term U.S. Rep. Madison Cawthorn’s (R-NC) claim that “I have built my staff around comms rather than legislation” could apply to quite a few members of his class.21Vesoulis, Abby. 2021. “Rep. Madison Cawthorn Peddles a Different Kind of Trumpism in a Post-Trump World.”Time. January 27. https://time.com/5931815/madison-cawthorn-post-trump.

Trump’s nomination in 2016 demonstrated a particular weakness of the Republican Party. Not only did he win the nomination contest despite the loud objections of many party leaders, most of those same party leaders fell in line behind him as soon as he had the nomination. Prominent public officials like Sen. Lindsey Graham, House Speaker Paul Ryan, Sen. Ted Cruz, and others who had publicly warned about the dangers Trump posed to both the party and the country very rapidly changed their tune and defended Trump through a range of his norm violations and even impeachable acts.22Lewis, Matt. 2019. “How Trump Broke In Lindsey Graham, Marco Rubio, Rand Paul, and Ted Cruz.” The Daily Beast. November 9. https://www.thedailybeast.com/how-trump-broke-in-lindsey-graham-marco-rubio-rand-paul-and-ted-cruz What this demonstrated was a party that could be transformed by a single person, even if an unusual one.

It also suggests a real weakness for American democracy. As Levitsky and Ziblatt23Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. 2018. How Democracies Die. Broadway Books. describe, parties play a vital role in limiting the access of would-be authoritarians to power. Indeed, early 20th century figures like Charles Lindbergh, Huey Long, and Henry Ford considered seeking national office but were essentially rebuffed by party leaders who were concerned about their dictatorial potential.24For more on the role of party leaders in screening out authoritarians, see Lesher 1994, Lowry 1923, Ceaser 1982. In an age of primaries, however, parties are far more likely to nominate such leaders.

Both major American parties, that is, have signaled that they are open to changes to the status quo in order to preserve their long term viability and protect American democracy.

The path from primaries to authoritarianism is hardly a direct one, much less an iron law of politics. Yet Polsby warned that the rise of presidential primaries would lead to an increase in factional presidential candidacies. That is, while party organizations were “coalition-forcing” entities, in primary elections “the politics of factional rivalry prevails,” in which it is each candidate’s best strategy to eke out just a few more votes than the next most popular candidate in a crowded field.25Polsby, Nelson W. 1983. Consequences of Party Reform. Oxford University Press. This encourages more populist-style electioneering, in which candidates seek to build a personal brand and maximize media attention, sometimes at the expense of commitments to the party or to democratic norms.

This trend was held at bay for decades, at the presidential level and in other nominations, with the help of elite coordination.26Cohen, Marty, David Karol, Hans Noel, and John Zaller. 2008. The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform. University of Chicago Press.27Hassell, Hans J. G. 2017. The Party’s Primary: Control of Congressional Nomination. Cambridge University Press. But many of Polsby’s concerns appear to be present in the 21st century. Trump’s own anti-democratic tendencies, of course, were on full display in 2016, but his party could not prevent his nomination. And the fact that he led an actual, violent, and well-documented attempt to overthrow a presidential election and yet remains a leading candidate for his party’s 2024 nomination suggests a real weakness and danger of the primary system.

Is there a way out of this problem? The outcomes of the 2022 midterm elections offer a few positive suggestions. First, congressional and gubernatorial candidates advocating overtly authoritarian stances under- performed in those elections.28Wallach, Philip. 2022. “We Can Now Quantify Trump’s Sabotage of the GOP’s House Dreams.” Washington Post. November 15. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/11/15/data-trump-weighed-down-republican-candidates. Second, this outcome contributed to what is arguably three consecutive Republican under-performances in national elections. Third, a surprising number of modern Senate and gubernatorial races, along with presidential races, have become highly competitive between the parties. These three factors give the parties incentive not only to nominate more broadly acceptable candidates but to turn to party leaders to enable that pivot. These incentives don’t secure an actual party change, of course, but they would seem a necessary condition.

The advent of primary elections came with the promise that they were making parties more “democratic” even though the concept of an internally democratic party is extremely elusive upon reflection. Several potential reform options would in that sense make parties less democratic. That is, it is unlikely that party voters are about to give up their nominal control over party nominations and their voice in primaries. Yet party leadership can assume greater control of the nomination process.

It is possible, as Kamarck29Kamarck, Elaine. 2017. “Re-inserting Peer Review in the American Presidential Nomination Process.” Brookings Center for Effective Public Management. April 27. https://www.brookings.edu/research/re-inserting-peer-review- in-the-american-presidential-nomination-process. suggests, for parties to assert a level of “peer review” to the nomination process, requiring party officials to approve of candidates before those candidates can run. Parties could raise thresholds for participation in debates or even for voting in primaries. Somewhat surprisingly, state parties often raise or lower primary voting participation thresholds without producing massive legitimacy crises30Jewitt, Caitlin, and Seth Masket. 2019. “When Parties Change Their Rules: Why State Parties Make Nomination Contests More Open or More Closed.” Presented at the Northeastern Political Science Association Conference in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 9.; perhaps they could do more in this direction.

As 2022 drew to a close, the Republican National Committee announced an internal review commission to examine a disappointing midterm election and proposed new paths forward for the party.31Isenstadt, Alex. 2022. “RNC Commissions ‘Review’ of Party Tactics after Disappointing Midterm.” Politico. November 29. https://www.politico.com/news/2022/11/29/rnc-tactics-disappointing-midterm-results-00071065. Meanwhile, the Democratic National Commission prepared to overhaul its approach to presidential nominations, dethroning the first-in-the- nation Iowa caucuses in favor of the South Carolina primary.32Sullivan, Kate, and Ethan Cohen. 2022. “Democrats Vote to Move Forward with Biden Plan to Put South Carolina First on 2024 Primary Calendar.” CNN. December 2.https://www.cnn.com/2022/12/02/politics/dnc-south-carolina-primary-calendar-2024/index.html. Both major American parties, that is, have signaled that they are open to changes to the status quo in order to preserve their long term viability and protect American democracy. This is an encouraging sign, and suggests that some of these reforms may indeed be considered.

The analysis, views, and conclusions contained herein reflect those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the American Political Science Association or Protect Democracy.

Related Content

Join Us.

Building a stronger, more resilient democracy is possible, but we can’t do it alone. Become part of the fight today.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy