More Than Red and Blue: Preface

- October 6, 2023

From More than Red and Blue: Political Parties and American Democracy

This report exists in no small part because of where we are currently in American political time. American politics and indeed American society are highly polarized and deeply divided. Many people from various vantage points are increasingly worried about the state of American politics. A good amount of the responsibility for this situation is laid at the feet of America’s two major political parties. While which party is more to blame depends on whom one asks, it is widely believed that today’s Republican and Democratic Parties have evolved to a place where they emphasize difference, stoke fear and animosity, and incite conflict. Indeed, if there is one thing on which deeply divided Americans agree, it is that parties have gotten us to the highly undesirable and dangerous place in which we currently reside.

During this fight for support, parties will exploit anything and everything they think will give them an advantage.

Americans’ consternation with and distrust of political parties is, of course, not a new development. Such feelings date to the earliest days of the republic and were in agreement on the necessity of parties. For them, the key to improving our current situation is to alter the political environment and/or rules of the game in such a way as to stack the deck in favor of parties as beneficial entities rather than harmful institutions. This is strongly held by many of the nation’s founders. Whether it be Madison1Madison, James. 1787. “Federalist No. 10.” The Federalist Papers. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed10.asp railing against “the mischiefs of faction” or Washington2Washington, George. 1796. “Washington’s Farewell Address to the People of the United States.”https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/resources/pdf/Washingtons_Farewell_Address.pdf warning his fellow Americans “against the baneful effects of the spirit of party,” many of the original architects of the American governing arrangement were strongly opposed to parties, as is noted throughout the chapters in this report. However, it is also true that many of these same figures soon turned to parties as the primary mechanism for advancing and enacting their agendas and goals. While not quite Schattschneider’s3Schattschneider, Elmer Eric. [1942] 2004. Party Government. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. “modern democracy is unthinkable save in terms of the parties” view, these American political practitioners came to the same conclusion that the generations of practitioners who came after them have reached: political parties are extremely useful, if not essential, in the practice of politics under the American governing arrangement.

One could argue that Americans today find themselves in this very same situation: they are deeply troubled by and distrustful of the place of parties in politics and government while at the same time reliant on political parties to accomplish their goals. The contributors to this report recognize this tension but find themselves more or less in agreement on the necessity of parties. For them, the key to improving our current situation is to alter the political environment and/or rules of the game in such a way as to stack the deck in favor of parties as beneficial entities rather than harmful institutions. This is where a brief history of American parties will prove useful. Political parties did not show up in American politics fully formed. American political parties have proven highly malleable and have changed significantly over time. There have been important continuities as well. Understanding these changes and continuities will not only help us make sense of where we are right now but will also prove useful in envisioning where we might go moving forward.

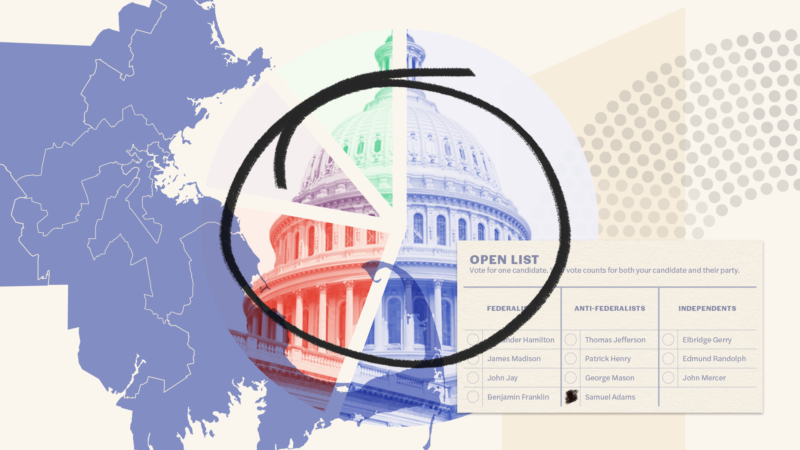

Despite appearing nowhere in the Constitution, presidential parties began forming before George Washington completed his first term as president. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s economic plans provided the initial partisan sparks, but the division soon grew to include fundamental questions of federalism and foreign policy as well. By the time Washington ended his second presidential term, the U.S. had its first party system (1796-1824)—the Federalist Party, led by Hamilton and John Adams, and the Jeffersonian (or Democratic) Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, but these parties were not like the parties of today. America’s first parties were elite parties, with their origins and members inside of Congress and the executive branch. This made sense as democratic elements were quite limited in the political system of that time. This began to change in the first two decades of the 19th century and, as this occurred, parties began to change as well.

The first American party system did not end abruptly so much as it gradually faded away. By the 1810s, the Federalists were reduced largely to New England, and, by 1820, they had disappeared entirely. Indeed, this so-called Era of Good Feelings is the only period of American history where there was only one major political party. The presidential election of 1824 brought this period to a close.4Banning, Lance, ed. 2004. Liberty and Order: The First American Party System. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund; Chambers, William C. 1963. Political Parties in a New Nation: The American Experience, 1776-1809. New York: Oxford University Press. This election featured four major candidates, none of whom got a majority in the electoral college. This threw the election to the House of Representatives where the leading vote getter in both the electoral college and the popular vote (in those states where it existed) — War of 1812 hero Andrew Jackson — was denied the presidency in favor of John Quincy Adams. This infuriated Jackson’s supporters, who felt their candidate deserved the presidency as the people’s choice. Jackson and his supporters immediately began looking toward the 1828 presidential contest, vowing to not be cheated again. It is in their efforts that the modern American party system emerges.

Jackson’s supporters recognized that their candidate was very popular with the masses and worked hard to maximize this advantage. Martin Van Buren, Democratic-Republican U.S. Senator from New York, took the lead in directing Jackson’s campaign and created a new model for seeking public office. Universal white male suffrage had been growing at the state level during the 1810s and 1820s, as had states selecting their electoral college electors by popular vote rather than by state legislatures. Van Buren used these changes to Jackson’s advantage and built the first grassroots party in the U.S.5Silbey, Joel H. 2002. Martin Van Buren and the Emergence of American Popular Politics. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. Jackson defeated Adams for the presidency in 1828, with the popular vote increasing more than three times than that of 1824. The days of elite parties In the U.S. were over. From 1828 forward, the major American parties would be the mass parties with which we are familiar today.

These developments ushered in the second American party system (1824-1860). The Democratic Party, as the Democratic-Republicans are now known, was opposed by the newly formed Whig Party. The Whigs learned from Van Buren’s example, and each party developed complex organizational structures at the local, state, and national levels to attract voters and recruit candidates. The two parties competed vigorously for supporters nationwide with muscular grassroots operations. The Democrats and Whigs took different positions on important issues, and they also appealed to voters based on sociodemographic characteristics and regional differences. Sometimes, this involved high-minded debates over substantive differences on policy. Other times, one would see unsavory appeals rooted in racial/ethnic, religious, or class differences, but all actions were aimed at winning elections.

The second party system came to end in the rising tensions caused by the debate over slavery and abolition. The Whigs collapsed and were replaced by the newly formed Republican Party, marking the beginning of the third party system (1860-1896). While the Civil War took place in this system’s early years, even here, the two-party system proved resilient. The Republicans came to dominate the northern states, and the Democrats were even more dominant in the South. While the Democrats and Republicans remained as the two major parties, the third party system would eventually end as well, giving way to the fourth (1896-1932), which gave way to the fifth (1932-1968), which at some point gave way to the sixth (1968-?). Parties scholars increasingly question if the sixth party system ended and if we currently find ourselves in the early stages of a still somewhat ambiguously defined seventh party system.

Each party system is, in many ways, unique, marked by differences in dominant issues, party coalitions, and partisan control. In addition to the potent legacy of the Civil War (both parties “waved the bloody shirt”), the third party system was marked by a significant rural/urban divide. The fourth party system saw conflict framed initially by currency issues and, later, fights over machine politics versus progressive reform. The fifth party system was the famed New Deal party system rooted in class differences and economic conflict while the sixth party system added racial and cultural conflict to the mix. It is not yet entirely clear what will dominate the seventh party system, if we are in fact in the seventh party system. Each party’s coalition also changed at least somewhat as each party system moved into the next, but, for the purposes of this report, it is perhaps more important to focus on the ways in which American party systems, at least since the second party system, have remained the same. The rules of the American political game are heavily stacked in favor of two major political parties. These two parties fight to attract voters at every level in the American federal arrangement. During this fight for support, parties will exploit anything and everything they think will give them an advantage. Issue positions, group identities and differences, election rules and laws, all are fair game in the eyes of parties as they pursue their ultimate goal — winning elections, so they can make public policy as they see fit. Keeping these facts in mind — facts that have been in place for almost 200 years — will be crucial in reading the chapters that follow. Parties are inherently neither moral nor immoral. They exist as a political means to a political end. If we want parties to behave in certain ways and contribute to certain outcomes, it is incumbent on us to create the conditions that will force them to do so.

The analysis, views, and conclusions contained herein reflect those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the American Political Science Association or Protect Democracy.

Related Content

Join Us.

Building a stronger, more resilient democracy is possible, but we can’t do it alone. Become part of the fight today.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy