Grant Tudor develops and advocates for a range of reforms to shore up our democratic institutions.

The “goldilocks zone” of political parties

- September 11, 2023

How proportional representation can create space for more parties — but not too many

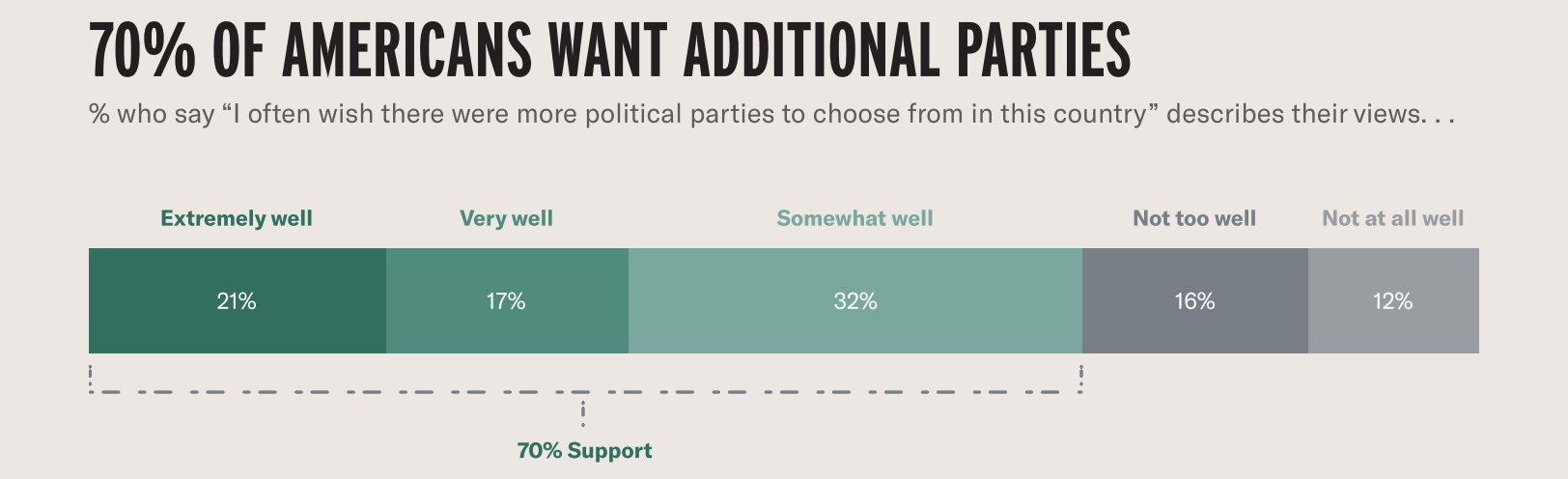

While more viable political parties can improve electoral competition, dampen polarization and provide greater opportunities for marginalizing extremist movements, they also risk “fragmentation”: a phenomenon where too great a number of parties produce overly “broad and fractious coalitions.”

Fragmentation can hamper effective governance. Indeed, one argument for winner-take-all systems has been the promise of “strong party government.” Fragmentation can also decrease voters’ ability to hold individual lawmakers or parties accountable. Thus, much scholarly discussion has focused on “optimal” electoral rules in order to maximize the benefits of multiparty systems and minimize fragmentation. In practice, the number of seat-winning parties across proportional systems varies widely. Israel, for instance, regularly features over two-dozen political parties in its legislature; none has ever won a majority of seats. Meanwhile, Uruguay features only three dominant parties, with other minor parties occasionally garnering a small number of seats. Both employ proportional systems — so what explains their differences?

The answer is generally “district magnitude” — the technical term for the number of seats per district. A single-member district has a district magnitude of 1, while a 20 seat district has a district magnitude of 20. District magnitude is the major constraint on the number of seat-winning parties. Legal thresholds are another, meaning that parties may be required to secure a certain threshold of the vote share in order to secure any seats. However, district magnitude “naturally” regulates fragmentation, predictably corresponding to the number of seat-winning parties. Simply put, the more seats there are up for grabs in a district, the greater the number of political parties that have a chance at winning at least one — and the greater the incentive for those parties to organize in the first place. Because district magnitude is a policy decision — determining the number of seats in any given district — it is also a practical lever to help regulate the number of political parties that are likely to emerge in a political system.

Read more: Towards Proportional Representation for the U.S. House Read more: Towards Proportional Representation for the U.S. House

While both Uruguay and Israel employ proportional systems, their party systems are radically different thanks to dramatic differences in their district magnitudes: in Uruguay, an average of 2.5; and in Israel, 120. Consequently, the number of seat-winning parties in Israel is nearly three times greater than in Uruguay. While Uruguay features only three major parties, Israel’s party landscape is highly fragmented and has long “experienced difficulties in building and maintaining large coalition governments.”

One large study of dozens of countries over decades finds that electoral systems with average district magnitudes of between four and eight generate highly proportional results, simpler government coalitions, and strong government performance “while limiting party system fragmentation” associated with larger district magnitudes. According to a quantitative model developed by Matthew Shugart and Rein Taagepera, assuming the overall size of the U.S. House remains constant, adopting proportional multi-member districts with an average district magnitude of four to eight in the U.S. would likely result in a total of three to four nationally competitive parties. We could think of this number as a “goldilocks zone” — moving beyond the rigidity of today’s two parties while avoiding the risks of fragmentation.

Adopting proportional multi-member districts with an average district magnitude of four to eight in the U.S. would likely result in a total of three to four nationally competitive parties.

Risks of fragmentation may also be offset in the U.S. context by characteristics unique to the U.S. political system. Our presidential system — with the presidency an inherently winner-take-all contest — will continue to favor the two major parties. Legislative parties in the U.S. are also strongly incentivized to build their respective coalitions around an independently elected and powerful executive, again favoring the largest and strongest parties. (Indeed, in other multiparty presidential democracies, multiple political parties tend to support a single political candidate from one of the major parties.) The same is likely true for state governorships. Similarly, winner-take-all elections for the Senate will almost certainly continue to favor the two major parties. Given these countervailing forces, average district magnitudes in the U.S. could likely afford to be even higher without inviting fragmentation.

District magnitude decisions invariably help to determine the number of competitive political parties in a political system, and should therefore be central to policy discussions regarding electoral system reform.

This analysis is adapted from Towards Proportional Representation for the U.S. House, published by Unite America and Protect Democracy. Read the full report here.

Related Content

Join Us.

Building a stronger, more resilient democracy is possible, but we can’t do it alone. Become part of the fight today.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy