How Did We Get Here: Understanding the Demographic Sources of America’s Party Divisions

- October 10, 2023

From More than Red and Blue: Political Parties and American Democracy

Abstract

This chapter examines demographic divisions in our partisan choices. It shows that race, more than anything else, divides us politically. Other demographic factors like religion, education, class, and gender are certainly relevant to our partisan affiliations. But race appears to be more central.

Moreover, the data also reveal growing divisions by race over time. A number of different factors help to explain these patterns. Americans’ partisan ties are in no small part due to economic anxieties, moral imperatives, and cultural concerns. But racial fears and racial views often predict our partisan choices as much or more than these other considerations.

IntroductionIntroduction

Two narratives tend to dominate our understanding of America’s partisan divide. One is about class and the other is about race. The class-based story argues that economic decline in working class communities is the main factor shaping support for the two parties.1Cramer, Katherine. 2016. The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. University of Chicago Press.2Drutman, Lee. 2016. “How Race and Identity Became the Central Dividing Line in American Politics.” Vox, August 30.3Gest, Justin. 2016. The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality. New York: Oxford University Press.4Hacker, Jacob S., and Paul Pierson. 2010. Winner Take All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer— and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class. Simon and Schuster.5McCarty, Nolan, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. 2007. Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches. The MIT Press. The other narrative is focused squarely on race. In this version, Republicans have won over an increasingly large share of the white vote not because of their economic agenda but rather because of a racial agenda.6Abrajano, Marisa, and Zoltan Hajnal. 2015. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.7Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson. 1989. Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.8Klinkner, Philip A., and Rogers M. Smith. 1999. The Unsteady March: The Rise and Decline of Racial Equality in America. University of Chicago Press.9Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial?: Race and Politics in the Obama Era. University of Chicago Press. From this perspective, many Whites feel that the growing racial and ethnic diversity of the nation’s population is threatening their grasp on power and privilege and are searching for answers to that threat — answers that the Republican Party often provides. Along with these two narratives, scholars and observers have also highlighted the growing impact of education and the increasing centrality of cultural concerns on the partisan choices of individual Americans.

Which version of these different accounts best explains the reality of party divisions today? This chapter will tackle this question in a number of ways. First, it will focus on the demographics of the vote. That assessment will compare race to class and other demographic factors to assess their relative contributions to the party divide. It will also investigate how these patterns have changed over time and, more specifically, how the nation’s political party system has transformed over the past half century. Last, the chapter focuses on the question of why this nation is divided along these different demographic lines. Are racial policies and racial attitudes at the core of the nation’s partisan divide? Or are economic and cultural considerations the dominant factors? And what else plays a role in separating us into two opposing partisan teams?

The answers are in many ways worrying. The data reveal that race sharply divides us along partisan lines — often more than any other demographic factor. Religion, economic concerns, and factors like education, age, and gender also divide us politically, but the reality is that as America becomes more diverse, it is also becoming more racially divided in the electoral arena. The literature identifies many reasons for these divisions and for changes in these divisions over time, but an account that focuses on race and in particular on racial fears and concerns often fits the data better than other alternative explanations.

What divides us?What divides us?

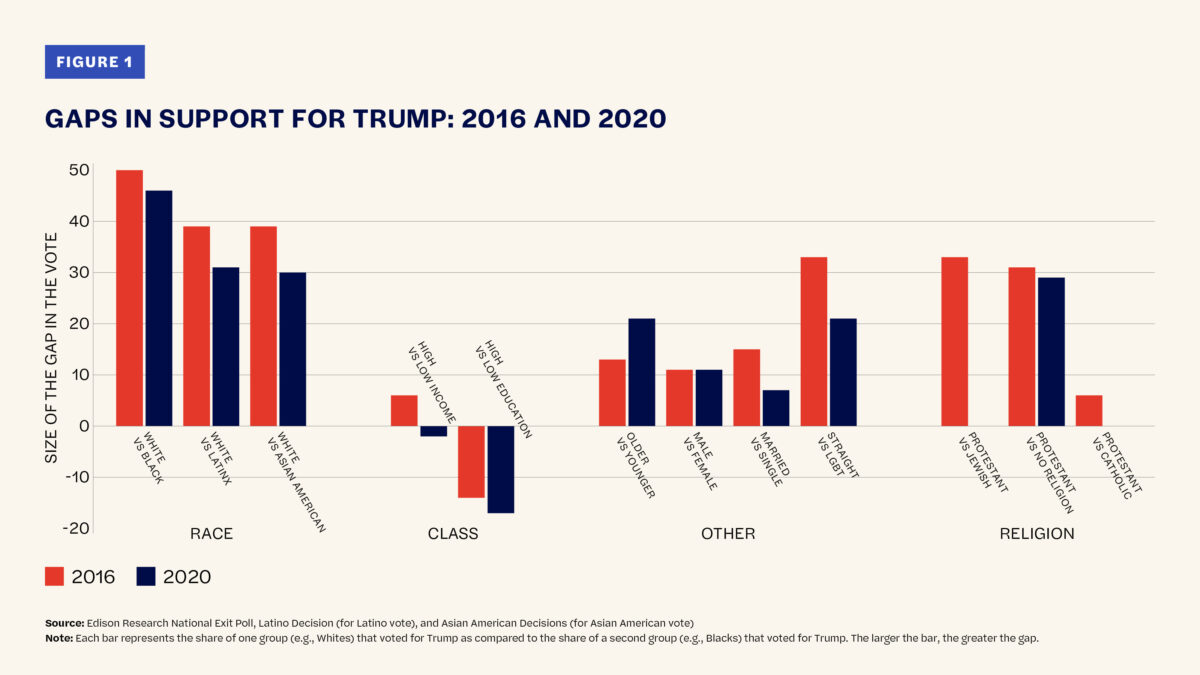

To begin to understand demographic divisions in party politics, the initial focus is on the vote in the last two presidential elections. Figure 1 below shows the size of the gap in the vote for Donald Trump in each election by race, class, and other factors. Each bar represents the share of one group (e.g., Whites) that voted for Trump as compared to the share of a second group (e.g., Blacks) that voted for Trump. The larger the bar, the greater the gap.

As Figure 1 shows, race played a more significant role in the outcome of both elections than did class. Exit polls in both contests revealed large gaps between racial and ethnic minority voters on one side and White voters on the other. Trump won only 8 percent of the Black vote in 2016. By contrast he garnered 58 percent of the White. That 50-point difference, shown in the first bar in the graph, is closer to a racial chasm than a racial gap. There were also sizeable gaps between Whites and Latinos and Whites and Asian Americans (both at 39 points in 2016). Despite the movement of some Latino and Asian American voters toward Trump in 2020, racial and ethnic identity still played a dominant role for voters. Simply judging by the size of the bars, race and ethnicity stand out as the most important force in American electoral democracy.

Class played a role in voter decision making in both the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections but not nearly as much as race/ethnicity did. Contrary to much of the popular wisdom, in 2016 Trump did slightly better among higher income Americans than he did among lower income Americans. The same was true in 2020, when he garnered 44 percent of the vote among Americans with incomes over $250,000 compared with 40 percent of the vote among Americans with incomes less than $30,000. When considering voters’ level of education, Trump did slightly worse as individuals’ education levels increased.

Why then did class attract so much media attention when the data reveals that class played a less central role in the vote? Part of the answer lies with the narrow focus of many of the media reports. Many studies focused on the narrow segment of the electorate that switched support from one political camp to another, from Obama to Trump, for example. But the reality is that less than 5 percent of the electorate switched from Obama to Trump. Moreover, even when scholars look more closely at these switchers, they find that racial attitudes, much more than economic concerns, predicted who would switch from Obama to Trump.10Sides, Jon, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis the 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Age, Gender, Religion and the Vote

Race and class are not, of course, the only narratives used to explain the outcome of recent elections. A lot of media attention focused on gender, age, religion, and other factors. With Hilary Clinton as the first female candidate from a major party running for president, gender was expected to be a major factor in the 2016 election. However, the final vote suggests it may not have been.11It is, of course possible that gender mattered in more subtle ways. Many believed that gender stereotypes shaped the coverage of the candidates and analysis of the vote itself finds that sexism among both men and women helped to shape the vote (Valentino et al 2018). Female voters did favor Clinton, and male voters did prefer Trump but neither by an overwhelming margin. In fact, the majority of White women (52 percent) supported Trump. In the end, the gender gap in 2016, as Figure 1 illustrates, was only 11 points. Similarly, despite significant attention to voters’ age, generation played a relatively little role in voter choice. Older voters (those over 65) were only 13 points more likely to favor Trump in 2016 than were younger Americans (those aged 18-24).

[T]he reality is that as America becomes more diverse, it is also becoming more racially divided in the electoral arena.

After race, the next biggest demographic influence on the vote was social morality and religion. Religion played a central role in shaping the 2016 and 2020 votes. Atheists, Agnostics, and Jews were especially likely to support the Democratic nominee, and Evangelicals, Catholics, and Protestants were particularly likely to support Trump. The increasingly central role of culture is also underlined by what appear to be increasingly large divisions by sexual preference. In 2016, LGBT voters overwhelmingly supported Clinton but straight voters were largely split between Clinton and Trump.

Other Elections

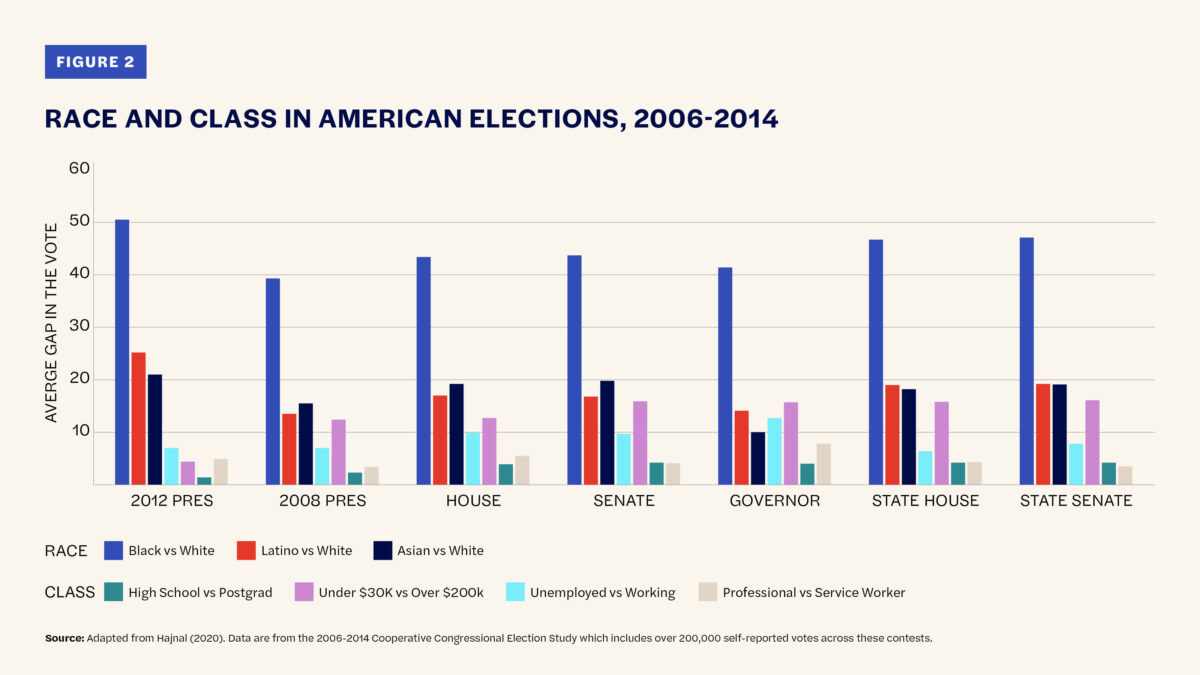

These two presidential elections are not aberrations. An examination of a much broader array of elections reveals much the same findings. In elections for both federal- and state-level offices from 2006-2024, racial gaps in the vote tend to dwarf class divides and most other demographic divisions, regardless of the type of contest.12Analysis of the 2022 midterms (though not shown in the figures in this chapter) leads to roughly the same conclusion.

Figure 2 illustrates the average gaps in the vote by race and class for each type of election between 2006 and 2014. It shows that the average black-white gap hovers between 40 and 50 points for almost all elections between 2006 and 2014. At each level, what Whites want is often not what Blacks want. But it is not only the black-white divide that stands out. The gap between white voters and Latino voters is typically a little less or a little more than 20 points across the different types of contests. Gaps between Asian Americans and whites are similar. In almost every type of office over this recent period, the majority of whites typically favor the candidate that the majority of Latinos, Asian Americans, and Blacks oppose.

Moreover, as Figure 2 illustrates, those racial divides generally dwarf divisions by class, indicated by level of education, annual income, type of work, and employment status. Americans with the highest levels of formal education — those with post-graduate degrees— only differ from those with the least formal education, defined as having less than a high-school degree, by an average of about 9 points in the typical contest. Income has a slightly larger but more variable impact on the vote. The preferences of Americans who earn less than $30,000 a year differ from the preferences of those who earn more than $200,000 a year by an average of anywhere from 4 to 16 points across the types of elections. Growing income inequality has received a tremendous amount of attention from scholars and the media, but race and ethnicity seem to have replaced class as the primary dividing line in American politics.13Hajnal, Zoltan. Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics. 2020. Cambridge University Press.14Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial?: Race and Politics in the Obama Era. University of Chicago Press.

Still, a range of other demographic factors have small but consistent effects across this wide variety of elections. The gap between younger (under 25) and older (over 65) Americans typically hovers around 10 points in these contests. The gender gap is roughly the same — about 12 points. Marital status plays a slightly larger role — typically, a little less than a 20-point gap between single and married Americans in how they voted for in this range of elections.

Although not featured in the figure, the main rival for race in dividing voters is once again religion. Americans who describe themselves as born again are about 25 points more likely to end up on the Republican side of electoral contests than are other Americans. Likewise, Americans who say that religion is very important to them are roughly 40 points more likely to favor Republican candidates for the House, the Senate, the Governor’s office, and state legislative positions.

Party Identification

One can get an even deeper look at divisions in American politics by focusing directly on party identification— the extent to which individual members of the public identify with one or the other major political party. Party identification is critical because research often shows that it structures much of our political thinking.15Bisgaard, Martin. 2015. “Bias Will Find a Way: Economic Perceptions, Attributions of Blame, and Partisan-Motivated Reasoning during Crisis.” The Journal of Politics 77 (3): 849-860.16Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. University of Chicago Press.17Goren, Paul. 2005. “Party Identification and Core Political Values.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (4): 881-896.

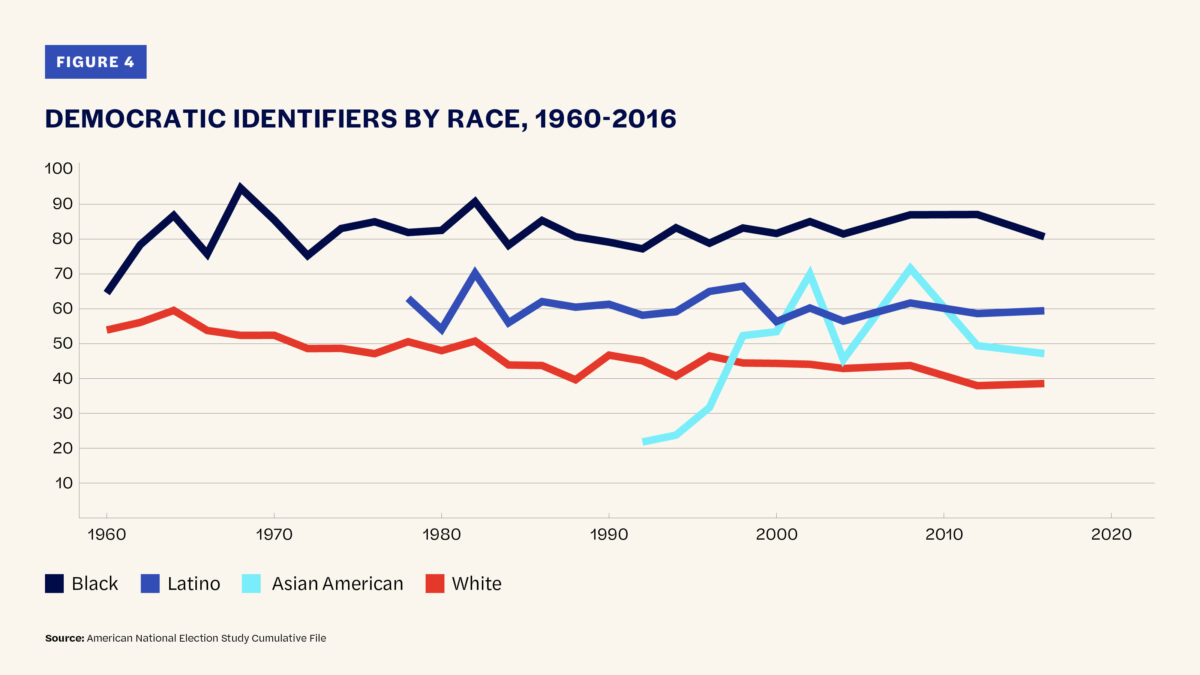

Thus, it is concerning to find that, racial patterns in party identification have roughly mirrored racial patterns in the vote in recent decades.18Hajnal, Zoltan. Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics. 2020. Cambridge University Press. The figure below, which shows the mix of partisan identities for each of the four major racial and ethnic groups over the last decade or so, reveals that racial and ethnic minorities largely identify with the Democratic Party (84 percent of African Americans, 60 percent of Latinos, and 59 percent of Asian Americans) over the Republican Party (7 percent of African Americans, 27 percent of Latinos, and 26 percent of Asian Americans).19In the figure, those who indicate that they “lean” towards one party are counted as partisans. By contrast, Whites are slightly more likely to identify as Republican than Democrat (46 percent vs 42 percent).

Thus, both through the candidates who are elected and patterns of political-party identification, Whites tend to align opposite racial and ethnic minorities in American democracy.20Again, it is worth noting that race better predicts partisanship than almost any other demographic factor. Divisions by class, age, and gender are very real but are much smaller than divisions by race. As with the vote, only religion rivals race in shaping partisan attachments. Moreover, race predicts both party identity and vote choice more than these other factors even when one controls for all of the different demographic factors in a single regression model. In other words, the effects of race do not diminish much even after controlling for class, gender, age, and the like. The data are surprising, disturbing, and insistent.

Partisan Attachments Over Time: We Are Becoming More Divided by RacePartisan Attachments Over Time: We are Becoming More Divided by Race

Race hasn’t always been central to the American partisan divide. Indeed, over a little more than a half a century, the American party system has slowly transformed from one in which one’s race didn’t tell us much about which party a citizen would support to the present-day system, in which one’s race, more than any other demographic factor, predicts who Americans support. Some of that transformation is illustrated in the next figures, which show the share of each racial and ethnic group identifying with the Democratic Party over time using data from the standard long-term sample of American electoral preferences — the American National Election Survey (ANES).

Beginning in the 1960s and continuing to the present day, there has been a slow and uneven shift of racial and ethnic minorities to the Democratic Party. African Americans have gone from largely Democratic in 1960 (64 percent) to overwhelmingly Democratic in recent years (81 percent in 2016). There is less data on Asian- American partisan preferences in early parts of this period, but since 1990, this population swung dramatically toward the Democratic Party. By 2010, Democratic identifiers outnumbered Republican identifiers among Asian Americans by almost three to one. Latinos are the only minority group to see no major movement in partisanship. For all of the years for which we have reliable data, very roughly 60 percent of Latinos have identified with or leaned Democratic. Overall, as more and more racial and ethnic minorities have entered the country and become engaged in the political arena, they have spoken with an increasingly clear partisan voice.

The past decades have also witnessed a substantial shift in White partisanship — with more and more Whites moving toward the Republican Party. White America has gone from largely Democratic (54 percent Democratic) in 1960 to just under 40 percent today. White Republicans now outnumber White Democrats by 48 percent to 39 percent.

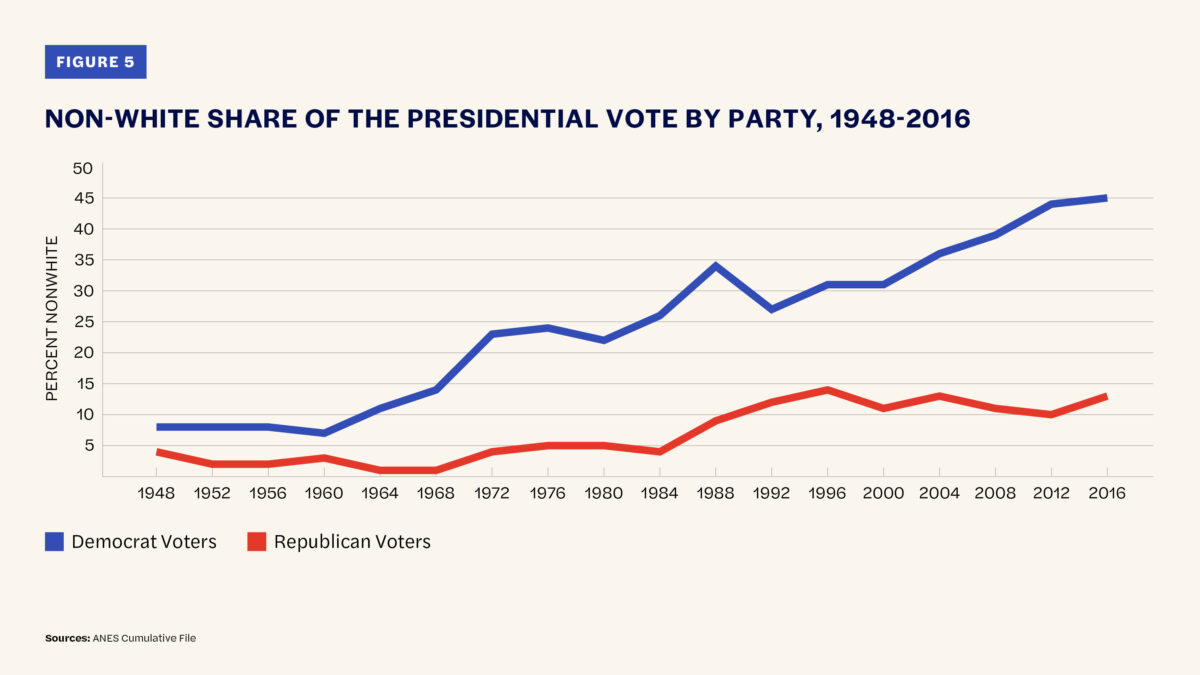

The net impact of these increased racial divisions is two parties with very different supporters. Figure 5, which shows the share of each party’s presidential vote that comes from non-White voters over time, illustrates this growing racial divide. Almost all the votes that Republican candidates have received in recent years have come from White voters. About 90 percent of the vote that McCain won in 2008, that Romney won in 2012, and that Trump garnered in 2016 came from White Americans. There was a slight shift in 2020, but 82 percent of Trump’s support still came from White America. The Republican Party is for almost all intents and purposes a White party.21Hajnal, Zoltan. Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics. 2020. Cambridge University Press.22Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial?: Race and Politics in the Obama Era. University of Chicago Press. By contrast, the share of Democratic Party votes coming from Whites has declined sharply since the 1960s. Today, almost half of all Democratic voters are non-White. Politics in America is by no means perfectly correlated with race, but it seems to be deeply and increasingly intertwined with race.

By contrast, there has been no clear increase in the importance of class in American politics over time.23Hajnal, Zoltan. Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics. 2020. Cambridge University Press. However, two important and likely related changes have occurred in recent decades within the White population. On the income side, the party preferences of the very rich have evolved from slightly Republican to slightly Democratic, while the less well-off have shifted from sharply Democratic to more mixed partisan preferences. The effect of education on the vote and on partisanship among White Americans has also shifted with the well-educated increasingly moving to the Democratic Party.24Drutman, Lee. 2016. “How Race and Identity Became the Central Dividing Line in American Politics.” Vox, August 30.25Piketty, Tomas. The Economics of Inequality. Harvard University Press, 2018.

Why have the parties aligned around race?

How did we get here? How and why do Americans choose political parties in the first place? And how is it that of all the potential divisions in American society, our politics have largely converged on race?

Understanding Party Attachments

Scholars tend to think of partisan identities as deep- seated psychological attachments that we learn early in life — often through parental socialization.26Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. University of Chicago Press. According to this traditional view — a view most academic researchers continue to adhere to — Americans often choose to align with a party as young adults and often without a lot of information. However, once attached our partisan identities become perceptual screens that not only shape what we learn about politics but also determine most of our political decisions from whether to vote to who to vote for.27Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. University of Chicago Press.28Green, Donald P., Bradley Palmquist, Eric Schickler, and Giordano Bruno. 2002. Partisan Hearts and Minds:Political Parties and the Social Identity of Voters. New Haven: Yale University Press. Just how this largely ‘inherited’ party identification has led to our current era of intense affective partisanship and to ever greater racial divisions in the vote is, however, not entirely clear.

An alternate view is that party identification is more thoughtful and is instead the result of the rational outcome of repeated evaluations of the issue platforms of the parties, the actions and sentiments of their elites, and the overall performance of the incumbent party.29Abrajano, Marisa, and Zoltan Hajnal. 2015. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.30Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.31Erikson, Robert. S, Michael B. Mackuen, and James A. Stimson. 2002. The Macro Polity. Spain: Cambridge University Press.32Fiorina, Morris P. 1981. Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press. Gest, Justin. 2016. The New Minority: White Working Class Politics in an Age of Immigration and Inequality. New York: Oxford University Press.33MacKuen, Michael B., Robert S. Erikson, and James A. Stimson. 1989. “Macropartisanship.” American Political Science Review 83 (4): 1125-42. Of course, if party identification is the result of rational updating, then the next question is obviously what is it exactly that individual Americans are updating on.

Racial Realignment Since the Civil Rights Movement

One obvious potential explanation for the patterns of partisanship illustrated above is that racial concerns have been the central factor driving the growing partisan divide. For most proponents of this racial realignment view, the primary driver of this racial transformation has been the decision of leaders of the two major political parties to offer increasingly divergent positions on matters of race and immigration.34Abrajano, Marisa, and Zoltan Hajnal. 2015. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.35Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson. 1989. Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.36Edsall, Thomas Byrne, and Mary D. Edsall. 1991. Chain Reaction: The Impact of Race, Rights, and Taxes on American Politics. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.37Lee (2002) and Schickler (2016) do, however, correctly note that the public and in particular the civil rights movement played a major role in driving the issue of race to the forefront of political discussions.

Seeing an opportunity to secure a national majority by giving Blacks access to the vote and therefore securing those new votes, elites in the Democratic Party began to publicly embrace the basic goals of the Civil Rights Movement. Then, having moved firmly to the left on race, the Democrats stayed there.

The other reason it’s hard to decipher the relative impact… is that race has now become closely intertwined with a range of ostensibly non-racial issues.

By contrast, elites within the Republican Party saw an opportunity to use race to appeal to Whites in the South, who were at that point overwhelmingly aligned with the Democratic Party but who were also deeply concerned about Black demands for racial equality. Employing what came to be known as the Southern Strategy, Republican politicians such as presidential candidates Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon ran campaigns that disparaged violence in the minority community and highlighted minority use of welfare and other public resources. Typically the message was subtle. But within a decade, the Republican Party had abandoned over a hundred years of racial progressivism.

According to this racial realignment view, the increasingly divergent platforms of the Democratic and Republican Parties on matters of race had their intended effects. First, as more and more Blacks felt that the Democratic Party was the most likely one to advance Black interests, Blacks shifted in ever larger numbers to the Democratic Party.38Dawson, Michael C. 1994. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Likewise, White Americans who opposed policies designed to help Blacks achieve greater equality abandoned the Democratic Party in ever larger numbers.39Hajnal, Zoltan. Dangerously Divided: How Race and Class Shape Winning and Losing in American Politics. 2020. Cambridge University Press.40Kinder, Donald R., and Lynn Sanders. 1996. Divided by Color: Racial Politics and Democratic Ideals. University of Chicago Press.41Zingher, Joshua. 2018. “Polarization, Demographic Change, and White Flight from the Democratic Party.”Journal of Politics 80 (3): 860-872.

By 1980, attitudes on race were closely correlated with party affiliation.42Carmines, Edward G., and James A. Stimson. 1989. Issue Evolution: Race and the Transformation of American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.43Valentino, NIcholas A., and David O. Sears. 2005. “Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South.” American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 672-88. And that link has only grown stronger over time. The effects of racial concerns heightened with the arrival and election of Barack Obama as the first Black President.44Highton, Ben. 2011. “Prejudice Rivals Partisanship and Ideology When Explaining the 2008 Presidential Vote across the States.” PS: Political Science and Politics 44 (3): 530-35.45Hutchings, V. 2009. “Change or More of the Same: Evaluating Racial Policy Preferences in the Obama Era.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73 (5): 917-942.46Kam, Cindy D., and Donald R. Kinder. 2012. “Ethnocentrism as a Short-Term Force in the 2008 American Presidential Election.” American Journal of Political Science 56 (2): 326-40.47Kinder, Donald R., and Allison Dale-Riddle. 2011. The End of Race? Obama, 2008, and Racial Politics in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.48Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Charles Tien, and Richard Nadeau. 2010. “Obama’s Missed Landslide: A Racial Cost?” PS: Political Science and Politics 43 (1): 69-76.49Parker, Christopher, and Matt Barreto. 2013. Change They Can’t Believe In: The Tea Party and Reactionary Politics in America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.50Schaffner, Brian F. 2011. “Racial Salience and the Obama Vote.” Political Psychology 32 (6): 963-88.51Tesler, Michael, and David O. Sears. 2010. Obama’s Race: The 2008 Election and the Dream of a Post-Racial America. University of Chicago Press. And their impact has persisted in more recent elections from Presidential to local.52Griffin, Robert, and Ruy Teixera. 2017. “The Story of Trump’s Appeal.” Democracy Fund: Voter Study Group.53Schaffner, Brian, Matthew MacWilliams, and Tatishe Nteta. 2018. “Understanding White Polarization in the 2016 Vote for President: The Sobering Role of Racism and Sexism.” Political Science Quarterly 133 (1): 9-34.54Sides, Jon. 2017. “Race, Religion, and Immigration in 2016.” Voter Study Group: The Democracy Fund.55Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial?: Race and Politics in the Obama Era. University of Chicago Press. Perhaps most convincing of all are studies showing that how one thinks about race at any one point in time strongly predicts future defections between the parties.56Kuziemko, Ilyana, and Ebonya Washington. 2018. “Why Did Democrats Lose the South? Brining New Data to an Old Debate.” American Economic Review 108 (10): 2830-67.57McVeigh Rory, David Cunningham, and Justin Farrell. 2014. “Political Polarization as a Social Movement Outcome: 1960s Klan Activism and Its Enduring Impact on Political Realignment in Southern Counties, 1960 to 2000.” American Sociological Review 79 (6): 1144-71.

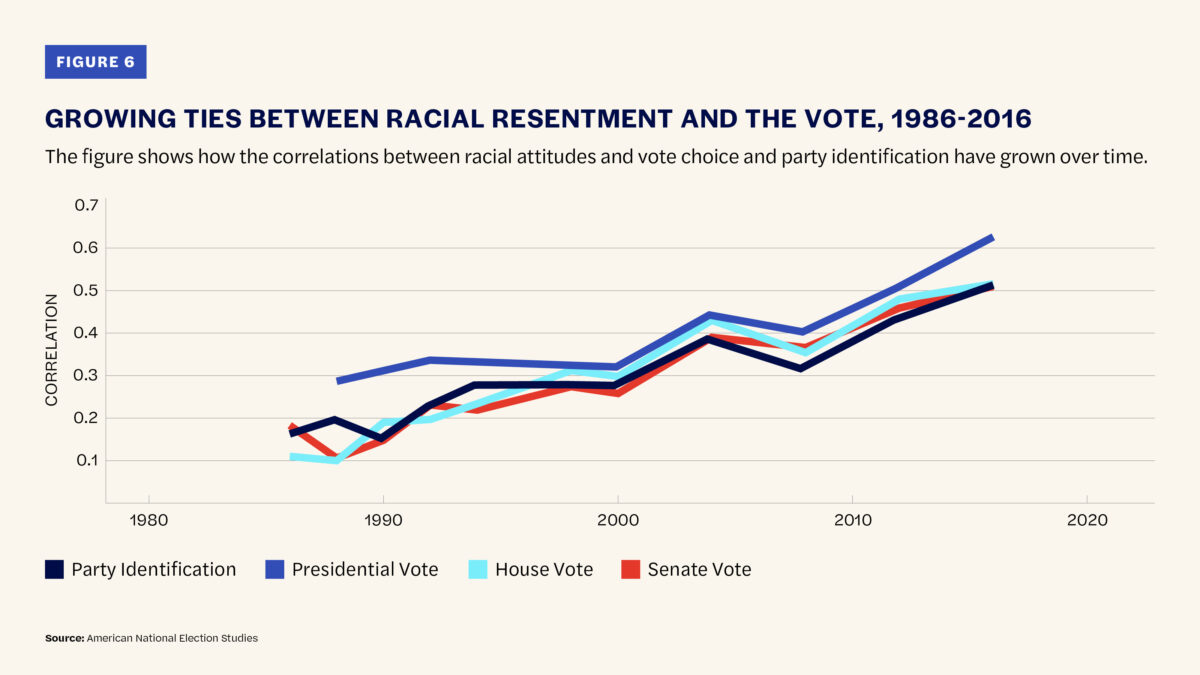

The increasingly strong effects of race on the political choices of Americans are reflected in Figure 6, which shows the correlation between how Americans think about African Americans — as measured by their score on a racial resentment scale58Items in the scale ask about things like whether Blacks deserve special favors, whether Blacks have gotten more than they deserve, and whether Blacks are trying hard enough. — and their party identity and votes over time. The figure shows that the connection between attitudes about race, the vote, and party affiliation has not only grown dramatically over time but has continued to do so in the Obama and Trump eras. Much of this growing relationship is driven by attitudes toward Blacks, but research has also revealed increasing ties between attitudes toward immigrants and partisan choice.59Abrajano, Marisa, and Zoltan Hajnal. 2015. White Backlash: Immigration, Race, and American Politics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.60Gimpel, James. 2017. “Immigration Policy Opinion and the 2016 Presidential Vote.” Center for Immigration Studies.61Griffin, Robert, and Ruy Teixera. 2017. “The Story of Trump’s Appeal.” Democracy Fund: Voter Study Group.62Mutz, Diana C. 2018. “Status Threat, Not Economic Hardship, Explains the 2016 Presidential Vote.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (19): E4330—E39.63Schaffner, Brian, Matthew MacWilliams, and Tatishe Nteta. 2018. “Understanding White Polarization in the 2016 Vote for President: The Sobering Role of Racism and Sexism.” Political Science Quarterly 133 (1): 9-34.64Sides, Jon, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis the 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.65Tesler, Michael. 2016. Post-Racial or Most-Racial?: Race and Politics in the Obama Era. University of Chicago Press.

Alternate Accounts of Party Realignment

At the same time, it is clear that much of the movement of Whites to the Republican Party — as well as some of the movement of racial and ethnic minorities to the Democratic Party — is not driven by race. Scholars have provided a range of other explanations for the current party divide that highlight ideological conflicts about the role of government, cultural concerns, economic considerations, and a range of other factors. Each of these factors has merits in explaining both partisan politics today and the growing racial divide over time.

For many, a debate about the proper role and size of government has always been and continues to be the core factor shaping our party system.66Abramowitz, Alan I. 1994. “Issue Evolution Reconsidered: Racial Attitudes and Partisanship in the Us Electorate.” American Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 1-24. Indeed, there is little doubt that liberals and conservatives have increasingly sorted themselves into two opposing parties.67De Abreu Maia, Lucas. 2022. “The Substantive Basis of Ideological Identification and its Behavioral Consequences in the United States.” Working Paper. Others maintain that cultural clashes over things like abortion, gays rights, and sexual identity have become more central in recent decades.68Adams, Greg. 1997. “Abortion: Evidence of Issue Evolution.” American Journal of Political Science 41: 718-37.69Carsey, Thomas M., and Geoffrey C. Layman. 2006. Changing Sides or Changing Minds? Party Identification and Policy Preferences in the American Electorate. American Journal of Political Science 50 (2): 464-477. It is clear that over time, leaders of the Republican and Democratic Parties have put forward increasingly divergent solutions to these cultural questions. It is also clear that as a result Americans’ views on moral and cultural issues increasingly help to predict their partisan affiliations. As many media and scholarly accounts have also highlighted, America’s growing income inequality has had substantial political repercussions. Anxiety over wages, jobs, and long-term economic prospects is clearly a powerful political force.70Abramowitz, Alan I. 1994. “Issue Evolution Reconsidered: Racial Attitudes and Partisanship in the Us Electorate.” American Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 1-24.71Shafer, Byron E., and Richard Johnston. 2006. The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Research offers strong empirical support for the influence of each of these factors in dividing Americans.

What is the relative impact of racial considerations?What is the relative impact of racial considerations?

The ultimate question is not whether racial views, economic considerations or cultural concerns affect the vote and partisan support but rather how much racial considerations matter relative to the other factors just mentioned. That is difficult, if not impossible, to answer. Part of the problem is complexity. Individuals are driven by a range of motivations and ultimately make their political decisions through uniquely complex pathways. One person’s motivations might even shift depending on the context, or a person might be weighing multiple considerations in one political instant.

The other reason it’s hard to decipher the relative impact of race and other factors on voter decision making and party affiliation is that race has now become closely intertwined with a range of ostensibly non-racial issues. For example, we now know that how individual Americans think about diverse policy issues — from welfare, health, and education to crime, taxes, and social security — are closely connected to how they think about race and immigration.72On the tie between race and welfare see Gilens (2001). On race and social security see Winter (2006). On race and gun policy see Filindra and Kaplan (2016). On race and healthcare see Tesler (2012). Going a step further, Americans’ attitudes about Latinos shape a number of policies related to immigration, education, and taxation (Abrajano and Hajnal 2015). Such research suggests the difficulty of disentangling attitudes about racial and ethnic groups from positions on other issues.

At the end of day it is clear that a range of different demographic and religious factors shape which Americans end up on which side of the party system. But it is also readily apparent that race divides us politically more than any other demographic factor. That was true before Donald Trump arrived on the scene and it is still true today. These divisions are also clearly getting worse. The reality is that as America becomes more diverse, it is also becoming more racially divided. Determining exactly what is driving those divisions is, however, a more difficult question. Racial considerations undoubtedly play a role but so too do divisions about the size and role of government, cultural and moral concerns, and economic considerations.

The analysis, views, and conclusions contained herein reflect those of the author(s) and do not reflect the views of the American Political Science Association or Protect Democracy.

Related Content

It can happen here.

We can stop it.

Defeating authoritarianism is going to take all of us. Everyone and every institution has a role to play. Together, we can protect democracy.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy