How to end gerrymandering

- August 20, 2025

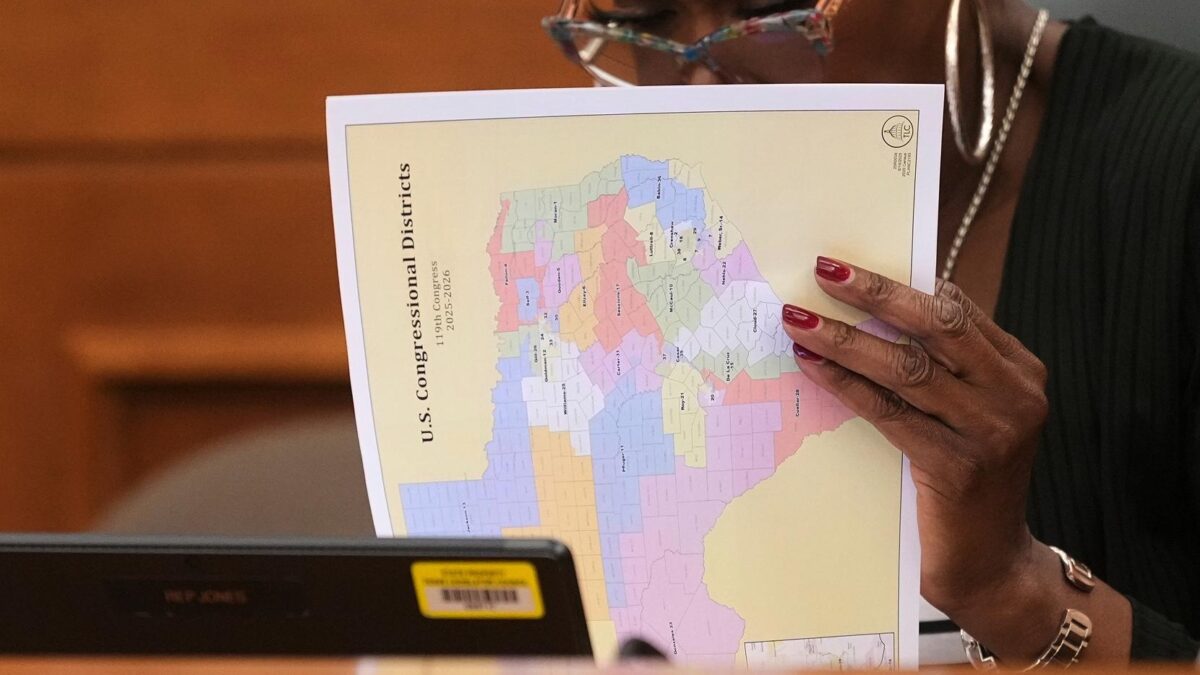

Gerrymandering is not new — the term ‘gerrymander’ itself comes from a signer of the Declaration of Independence. And yet, even as 90 percent of Americans disapprove of politicians drawing districts to benefit themselves, there’s a reason why it’s so hard to kill: Our electoral system has a design choice that makes it uniquely vulnerable. That defect is the result of one law, the Uniform Congressional District Act of 1967 (UCDA), which requires states to draw single-member districts for the House of Representatives.

Read more: Proportional representation, explained Read more: Proportional representation, explained

Single-member districts are easy to manipulate. It’s not hard for line-drawers to predict which party will have an advantage by packing a district with supporters, or by splitting up the opposition by drawing a line right through them. It’s no coincidence that countries with single-member districts are uniquely susceptible to gerrymandering. As one global study concluded:

Not all electoral systems are equally prone to gerrymandering. The problem is inherent in the system of one-seat districts.

Want more Democracy Insights?Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

Most modern democracies don’t have legislative districts represented by only one legislator — which is why most don’t struggle with gerrymandering like we do. Instead, a majority of democracies today use proportional multimember districts (we’ll get back to what this means in a bit), which makes gerrymandering “prohibitively difficult” in practice, in the words of that same study. Our decision to use single-member districts makes gerrymandering possible in the first place.

The good news is that our Constitution doesn’t require them. It’s a choice we’ve made. To understand why the gerrymandering wars persist — and to actually stop them — we need to get to the root cause. Yes, there are bad and better maps, and bad and better people to draw the lines. But under a single-member district system, gerrymandering is difficult to shake.

There are no perfect maps under single-member districts

Reformers have been trying for a long time to ensure fairer maps. But there is no such thing as a flawless one. When each district has one (and only one winner), those flaws are often very serious and practically impossible to avoid.

If we put aside the many states that aren’t even trying to draw fair maps and look only at good-faith redistricting efforts, even then the process can never be perfect.

As voters, we rightfully want lots of things from our electoral maps. Among others:

- To be fair in partisan terms and not systematically advantage either party.

- To represent distinct constituencies, especially racial groups, and ensure that they aren’t shut out of Congress.

- To be competitive.

- To be compact and logical in representing cities and neighborhoods.

- To make elections administratively easier by following county lines and other political geography.

Accomplishing all of these, instead of just balancing between them, is an impossible task.

Even in the best-case scenario, single-member districts have to pick and choose between conflicting priorities. As Americans have geographically self-sorted into red and blue areas, creating competitive districts (when possible) requires contorted lines combining rural and urban areas. Maps that are “fair” in aggregate often look distorted up close. And since minority constituencies are rarely a majority in any specific geographic area, sometimes the only way to ensure representation is to intentionally draw non-compact districts, as the Voting Rights Act rightfully requires.

But here’s one of the biggest problems: Even if we got rid of gerrymandering, biased outcomes — the thing we really care about when we talk about gerrymandering — will persist as long as we have single-member districts.

For example, take a look at the two states that have virtually no gerrymandering, California and Massachusetts. California’s independent redistricting is often regarded as the “gold standard” of independent commissions. The commission is well-regarded by anti-gerrymandering advocates because it is composed of members of both major parties and unaffiliated commissioners, its members are citizens rather than elected officials, and the state legislature doesn’t have the power to override the lines drawn by the commission.

In California, though, while Democrats win about 60 percent of the vote statewide, they capture about 80 percent of congressional seats. If the commission has virtually eliminated gerrymandering — lines are not intentionally drawn to favor one party over another — why, then, do Democrats still have a dramatic advantage? It’s not because the commission is biased. Instead, the commission can’t eliminate bias because it’s constrained by other criteria — namely voting rights compliance, compactness, and the integrity of local communities of interest (i.e. making sure an entire town is represented by the same member of Congress).

Learn more about the tradeoffs faced by independent commissions. Learn more about the tradeoffs faced by independent commissions.

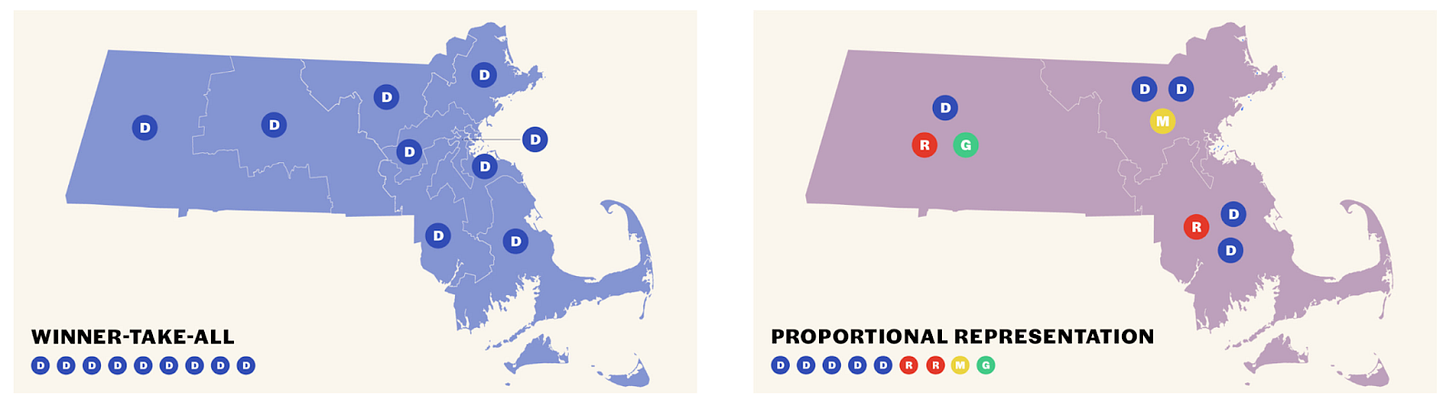

On the other side of the country, in Massachusetts, Republicans receive a little more than a third of the statewide vote, but of the state’s nine U.S. House seats, they win none. The cause isn’t gerrymandering; in fact, if anything, district lines in Massachusetts slightly favor Republicans. The problem is single-member districts. Republicans are too geographically dispersed across the state and don’t constitute a majority in any one district.

In fact, based on how Massachusetts have voted historically, there is no possible map that would result in anything other than nine Democratic-leaning congressional districts. Seriously. It’s mathematically impossible — a group of mathematicians found that: “Though there are more ways of building a valid districting plan than there are particles in the galaxy, every single one of them would produce a 9–0 Democratic delegation.” (Of course, if the results of the 2024 presidential election indicate that Massachusetts is getting redder, this could change based on the composition of the voters.)

Read more: Proportional representation and gerrymandering Read more: Proportional representation and gerrymandering

Even though independent commission-drawn maps are a substantial improvement on those drawn by politicians — and a national gerrymandering ban may be critical to stop the downward spiral — no redistricting process is going to draw perfectly fair maps.

Our single-member districts system leads to unrepresentative outcomes, stifles competition, and exacerbates polarization and extremism — in addition to setting the stage for intense redistricting fights and power grabs like we’re seeing this week.

The solution is simple and achievable

But there is a solution. A system that would end boundary-drawing brawls and make our democracy more effective, inclusive, and representative. It’s called proportional representation. How it works is intuitive: Share of votes equals share of seats.

Let’s go back to Massachusetts with its nine Democratic-leaning congressional districts. With proportional representation, if the vote share was 70%-30%, then Democrats would win about 70% of the seats, instead of all of them.

Under proportional representation, we can have it all. The same map can be competitive and fair, representative and compact. Racial minorities can be represented even when they don’t live in the same area. District lines can much more easily follow existing political and real-world geography.

Read more: Proportional representation and the Voting Rights Act Read more: Proportional representation and the Voting Rights Act

Plus, because it creates more competition and a more representative system, proportional representation opens the door for more politically viable parties, more coalition-building, and more cross-ideological allegiances. A more representative government with more incentives for compromise and moderation could also mean a more responsive, effective government.

For more, here’s Protect Democracy’s Farbod Faraji on how this all works:

And proportional systems are much harder, if not impossible, to gerrymander — because voters’ representation is based on how they vote, not where they live. It’s easy to make the opposition a minority in any given district. It’s impossible to draw them out entirely.

Even in the reddest and bluest parts in the country, at least one in five voters routinely vote for the other party. That’s enough for both sides to be represented everywhere.

Whether Republican voters in western Massachusetts are drawn into Massachusetts’ first or its second congressional district, they will still be represented by the same number of members of Congress because they represent the same percentage of voters in either district — even when they’re a minority.

Just as importantly, proportional representation isn’t a pie-in-the-sky dream. Because the constitution is silent on how many members may represent each district and how districts are drawn, Congress could amend the UCDA to require proportional representation. They could do it tomorrow, on a national level, through regular lawmaking. None of this requires a constitutional amendment. (Proportional representation can also be implemented on the state level through legislation or ballot initiatives — for example, see the ongoing effort in California.)

There has never been a better moment for ambitious reform

Obviously, this will not happen under the current Congress or president. And there are real and difficult questions around what pro-democracy actors need to do to prevent an authoritarian and his allies from using gerrymandering to seize power permanently. But if we really want to strengthen Americans’ commitment to democracy, we also have to work to make it better — not just preserve a flawed and outdated status quo.

Voters are increasingly disillusioned with our current two-party system — built around a zero-sum game of single-member districts — meaning the majority of Americans are hungrier than ever for systemic change.

But there is a way out of this doom loop, and it’s simpler and more achievable than most people think — proportional representation.

Related Content

Join Us.

Building a stronger, more resilient democracy is possible, but we can’t do it alone. Become part of the fight today.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy