Ben Raderstorf is a policy advocate at Protect Democracy. He helps direct policy and communications work around systemic threats to American democracy and writes If you can keep it, our weekly email briefing.

Op-ed: The Thanksgiving table approach to fixing American politics

- November 23, 2023

Our country’s strength comes from diversity of opinion. Let’s design our elections accordingly.

This op-ed was published in The Miami Herald.

When Americans think about Washington this Thanksgiving, few will find much to be thankful for. According to a poll our organizations released this week, less than half of voters feel represented by their congressperson, and two-thirds of Americans don’t feel represented by Congress as a whole. A similar number wishes there were more than two parties in Congress.

Despite our collective discontent, the problems of representation feel so ingrained that it’s hard for most of us to imagine anything different, let alone better.

Many political scientists agree that breaking out of our democracy crisis is going to take ambitious reform, likely something called “proportional representation.” Not familiar with it? You’re not alone, 59 percent of Americans have never heard of it.

Technically speaking, proportional representation is an electoral system that elects multiple representatives in each district in proportion to the people who vote for them. It is the most common electoral system in democracies worldwide.

To explain how it works, we often use the metaphor of a Thanksgiving dinner.

Imagine that the country is going to sit down for Thanksgiving together and we need to decide what to cook. (This may sound silly, but it’s not that far off from real world legislating and governing — we need to translate 332 million individual preferences into specific policy choices. One pie gets baked, one program gets funded.)

There are two fundamentally different ways we could plan the menu.

First, we could split the country up into even groups, geographically, with each group tasked with bringing one — and only one — dish to dinner. Whatever dish has the most support in each group would end up on the table. Chances are, most districts would pick one of the two most popular dishes, and over time, we’d start to define ourselves by which we preferred.

This is more or less how we elect Congress. We have 435 House districts, and each picks one person to send to Washington. This makes our elections “winner-take-all” because, in each race, one winner gets all the representation and everyone else gets nothing. This is the reason the United States has the world’s strictest two-party system: when forced to choose only one option, our politics have cohered into two warring camps.

Alternatively, we could design our Thanksgiving menu more holistically. To do this, we’d have the country decide on a list of dishes, proportional to voters’ preferences. So the stuffing and turkey would be dominant, but the mashed potatoes and candied yams would still make the cut.

This is the idea of proportional representation. With multi-member districts, each electing multiple legislators, more parties win representation simultaneously, and voters are represented even if they aren’t in the majority. And like mashed potatoes, we’re more likely to have our priorities on the table when more than one person wins.

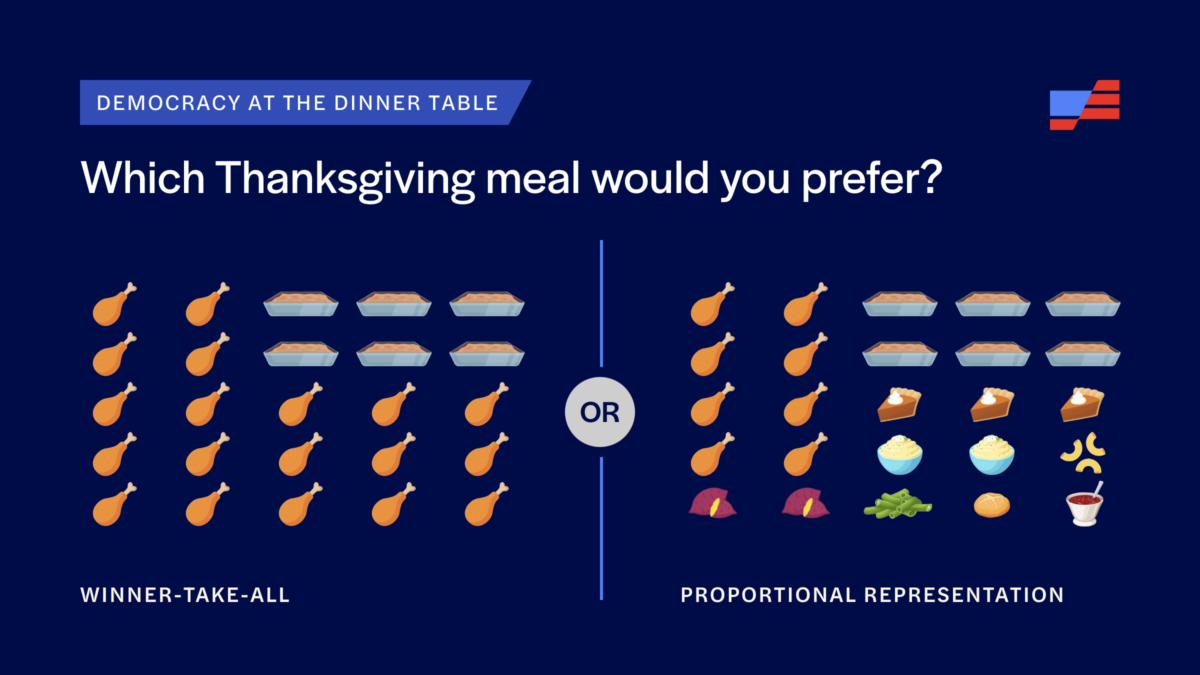

We have used this thanksgiving dinner metaphor for a long time. But this year we decided to test it. So we ran a nationwide poll, asking voters: “what’s your favorite Thanksgiving dish?” Then we ran the responses through two electoral systems. First, winner-take-all: we split the country into census districts and “elected” the most popular dish in each. In the second, we pooled the responses and any dish with more than 5% support got elected.

Unsurprisingly, the proportional representation table looks pretty tasty: beyond turkey and stuffing and potatoes, the menu includes sweet potatoes and mac n’ cheese and cranberry sauce.

The winner-take-all thanksgiving? Just turkey and stuffing stuffing. Every single census district brought either turkey or stuffing to dinner.

Crucially, the stakes go beyond representation. It’s not just that our two parties aren’t sufficiently diverse — it’s that only having two options is turning us into angry tribes. It’s gotten so bad that one of the two parties would rather overthrow the Constitution than accept defeat.

As anyone preparing for a turn to politics at family thanksgiving knows, binary conflict can be disastrous. Our winner-take-all elections are turning otherwise healthy disagreement into a head-to-head standoff, like drunken uncles fighting for political dominance.

We should instead work towards a system that allows more than two perspectives — like your Gen Z cousins breaking the tension with a joke. Studies find that countries with proportional representation are less polarized than those with winner-take-all. Why? According to political scientist Jennifer McCoy, proportional representation “allows a variety of views to be represented and enables more fluid coalition building that can break the binary divisions.”

Just like families around a Thanksgiving table, this country is strongest not when we clash over us-versus-them politics, but when we learn to make space for disagreements. We should reform our elections to embrace healthy, multidimensional, and civil debate — capturing the complexity of a diverse country — instead of reducing our differences down to winner-take-all.

Ben Raderstorf is a policy advocate at Protect Democracy, a non-partisan, anti-authoritarianism group. Mindy Finn is CEO of Citizen Data, a polling and analytics firm, and was an independent vice-presidential candidate in 2016.

Related Content

It can happen here.

We can stop it.

Defeating authoritarianism is going to take all of us. Everyone and every institution has a role to play. Together, we can protect democracy.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy