Jennifer Dresden is a Policy Strategist at Protect Democracy, where she helps teams leverage leading social science research to inform their work in defense of democracy.

Why are democracies reeling?

- November 1, 2022

Since the mid-2000s, global democracy — seemingly on the rise for decades — has entered a prolonged recession. Since then, democracy’s decline and authoritarianism’s rise have affected every region of the world, with erosion in both new and established democracies. The speed and scope of this wave surprised many experts, especially its inclusion of some of the world’s oldest and most stable democracies like the United States.

On paper, a democracy as politically established and economically developed as the United States should be resilient, even in the face of global pressures and challenges.

So why is our democracy reeling instead?

To date, there’s no consensus explanation for what’s driving this process. But several theories have emerged to help explain why the commitment to democracy is weakening.

Globalization has not benefited all equally

Hand in hand with the expansion of democracy around the world has been the increasing globalization of the economy and information landscape. Yet the explosion of cross-border exchanges of goods, services, ideas, and people has benefited some more than others, and in some cases either exacerbated or drawn more attention to those divides.

Globally, the poorest have benefited from globalization, with worldwide poverty dropping by more than two-thirds between 1988 and 2013. The wealthiest have similarly benefited. But those in the middle class — typically the bedrock of democracy around the world — have benefited least in many countries. In the United States, middle class wages have seen decades of stagnation or middling growth. Urban and rural Americans also face wildly different economic landscapes, adding a geographic element to the picture.

Academics often distinguish between people who value democracy intrinsically for its own sake and those who value it for the other good things it brings them. (And, to be clear, in the aggregate, democracies do out-perform autocracies in vital ways.) But for the average voter, a political system that fails to provide results for their day-to-day quality of life hardly inspires devotion. Anti-system politicians, including many would-be authoritarians, have a fertile base of potential support when voters no longer believe democracy can deliver.

When social bonds break down, democracy suffers

Recent decades have been marked not only by increasing globalization and economic inequality, but by the breakdown of some of the essential connective tissue of society. While the links between countries and across space have multiplied, many traditional communities and institutions have waned around the world. The United States is no exception, and analysts from all ideological backgrounds have pointed to these trends.

Whether because of technological change, demographic shifts, or the increasingly “sorted” nature of our public spaces, Americans are simply less closely connected to one another in meaningful ways. Civil society participation is down, feelings of social isolation or loneliness are up, and the physical spaces where Americans can meaningfully encounter and build relationships have significantly receded. Online platforms are no substitute when social media algorithms ensure that users typically see only content with which they agree.

This matters for democracy. Practically, the social capital that accompanies robust social engagement and connection facilitates democratic participation. It makes it easier to rally support for a measure before the town council or to find a ride to the polls on election day. Social engagement also fosters the kind of generalized trust that is essential both for the losers of elections to accept being governed by the winners, and for voters to believe, for example, that their ballot was properly counted in good faith.

The breakdown of conventional social connections and structures has also not been uniformly replaced by a new consensus on widely-shared identity or values. As people become more isolated from one another and less connected to a sense of common purpose, polarization and divides grow. Leaders can exploit these dividing lines to solidify loyalty among supporters, selling a narrative of connection and meaning that pits them against the “other side,” with whom actual encounters are all too rare. Changes in the technology and media landscape accelerate this process.

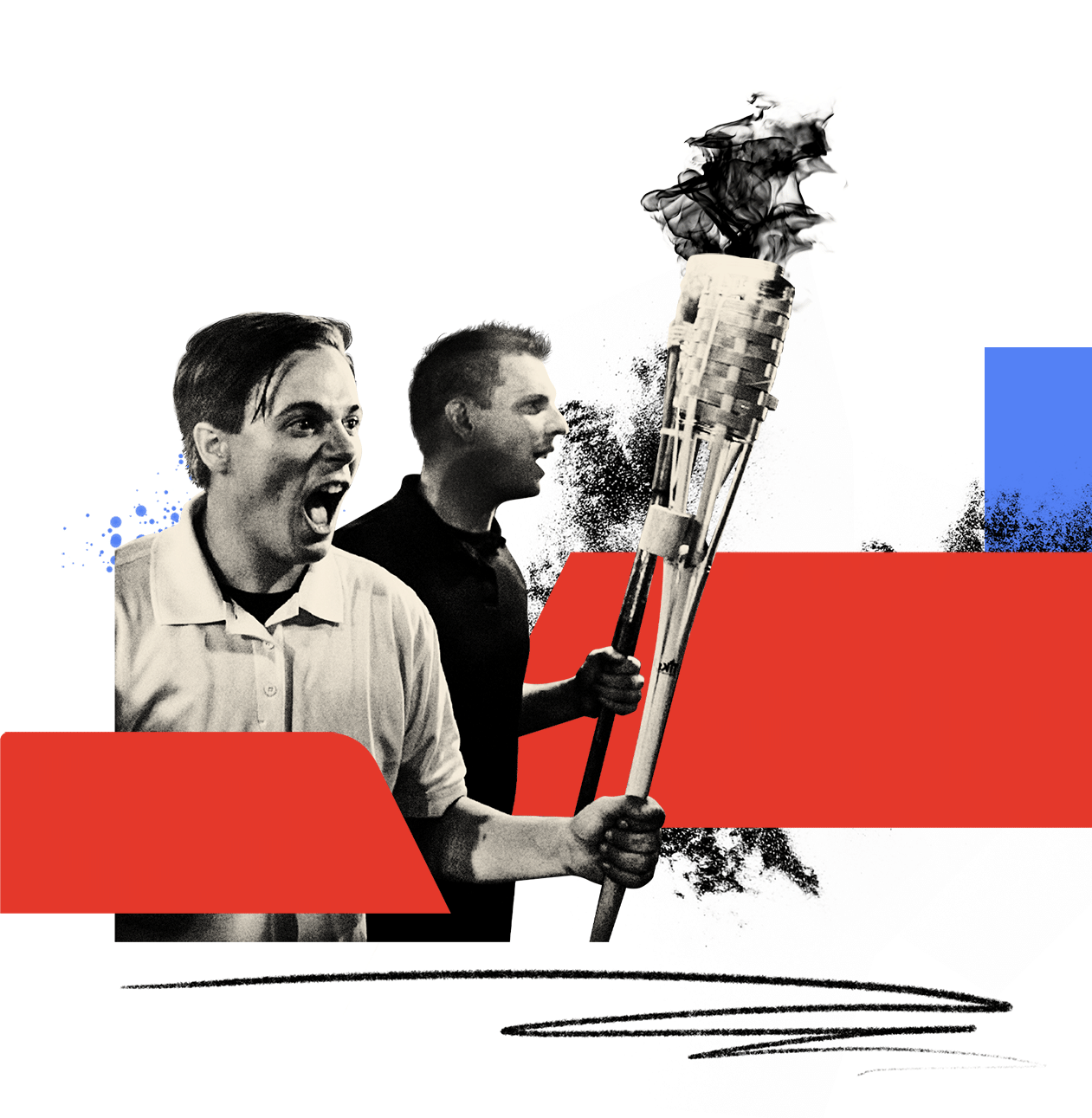

Backlash to demographic and cultural change targets democratic fundamentals

Economic, social, and technological changes underlie much of the democratic weakness across the world. But the authoritarian threat in some places, including the United States, is shaped by another central development: rapid and extensive demographic change. Just as many of the social patterns that organized peoples’ lives in prior decades have fallen away, the composition of American society has fundamentally shifted. The hierarchies that once gave some Americans privileged status at the expense of others have begun to break down with these demographic changes and increasing attention to questions of justice and equity, particularly in matters of race.

As democracy incorporates and empowers historically marginalized groups, some people resent the loss of their previous dominant status. When members of marginalized groups win elections and govern, that resentment becomes acute. The very elements of democracy that ensure political inclusion and equal treatment under the law become a source of dissatisfaction. Leaders who pander to these resentments and dissatisfactions for political advantage then face no political penalty for dismantling essential elements of our democracy. In this way, the current challenges for our democracy echo earlier periods in which the United States struggled with backlash and resentment.

Another version of this backlash is cultural, as much as demographic. On this theory, some of the cultural shifts that exemplify the latter decades of the 20th and early 21st Centuries in many advanced democracies — from a focus on personal autonomy and the prioritization of expressive values, to sexual liberation and gender equality, to secularization — have caused another form of backlash that has, among other things, shuffled political allegiances and even commitments to a democratic form of government.

Adding it all up

All of these explanations — economic change, social atomization, and backlash to demographic and cultural change — contribute at least partially to the pressures that are undermining democracy in the United States.

These pressures have built up in recent decades and weakened some of the key foundations of stable democracy. In theory, that pressure could find an outlet in reforms that improve governance or make politics more responsive. But that is not what we’re seeing. Instead, accelerants such as polarization, new media, and an electoral system that advantages extremism have left democracy vulnerable to leaders who see political opportunity in an ever-weakening system.

As more and more political leaders capitalize on this vulnerability, our political system tilts further and further off balance. At this point, it is wishful thinking to hope that our democracy will self-correct and recover automatically. Without a reinvigoration of the checks and balances of our system, defense of the rule of law, vigilant protection of our elections, and bold thinking for building a democracy that meets the challenges of today and tomorrow, American democracy will struggle to regain its footing.

Read More – Advantaging Authoritarianism: The U.S. Electoral System & Anti-Democratic Extremism Read More –

Related Content

It can happen here.

We can stop it.

Defeating authoritarianism is going to take all of us. Everyone and every institution has a role to play. Together, we can protect democracy.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy