Understanding domestic National Guard missions

- August 5, 2024

Deciding whether to deploy the National Guard on U.S. soil presents unique considerations that policymakers should always weigh judiciously, especially in an election year.

Election years increasingly bring elevated risks for the nation’s security, and 2024 has proven to be no exception. The exceptionally polarized political environment has highlighted the challenges facing one of our most important apolitical institutions: the National Guard.

Since 2020, there has been a growing trend of nontraditional deployments of the National Guard on U.S. soil by leaders from both political parties to, among other things, teach in public school classrooms and patrol subway stations. Such deployments create additional stress for Guard members, most of whom have civilian jobs they must put on hold when called into service, compound strain on their families and civilian employers, and consume billions of taxpayer dollars. A nonpartisan group of retired high-ranking civilian and military leaders (whom Protect Democracy sponsors) have responded by publishing a Statement of Principles outlining the factors policymakers and the public should consider when evaluating potential and actual domestic deployments of the Guard. That group, Count Every Hero, works to promote a healthy democracy as a cornerstone of our national security. The principles provide a helpful tool to discuss what the traditional roles of the National Guard actually are, why that’s important, and why we need to pay attention to these missions that depart from those norms. Especially in a year when millions of Americans will exercise their fundamental right to vote, every effort must be taken to avoid even the impression of interference by the U.S. military — an imperative the principles highlight alongside the need to keep the National Guard ready for any emergency that may arise.

The roles of the National Guard and how it functions

The National Guard occupies an unique position in the U.S. military because of its dual mission: operating both as 54 state and territory-based militias and as a reserve component of the armed forces. Going beyond conventional military activities, the Guard performs a variety of roles including supporting disaster relief, responding to civil unrest, and carrying out other duties with the goals of saving lives and protecting property.

The United States has a longstanding (if imperfectly followed) tradition of limiting the role of the military in domestic affairs. The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878 bars members of the U.S. Armed Forces from participating in domestic civilian law enforcement activity absent congressional authorization. However, this statute does not apply to National Guard units when they are under state control — their default status — and governors may employ the Guard to engage in law enforcement when needed.

When National Guard personnel are activated, they serve in one of three duty statuses:

- In “State Active Duty” (SAD) status, National Guard members are under the command of the governor of the state in which they serve and their mission is funded by the state. In SAD operations, governors enjoy wide latitude to use the Guard forces they command as they see fit, in accordance with state law.

- In “Title 32” (or “hybrid”) status, Guard personnel operate with federal funding while remaining under the command of the state governor, pursuant to Title 32 of the U.S. Code. While this status is normally used for training exercises to promote readiness for traditional military missions, it has also been used for federally funded disaster relief efforts, such as the Guard’s mobilization in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Guard units under state control may be called upon to support federal missions at the president’s request, with the consent and at the command of the state governor. You can read our colleague Christine Kwon’s work on questionable uses of Title 32 here.

- In “Title 10” status, Guard personnel are federalized by the president under Title 10 of the U.S. Code and serve under federal command and control. Guard units under Title 10 status operate as part of the U.S. Armed Forces and can be deployed overseas for combat missions. Domestic deployment of the Guard under Title 10 is illegal absent express congressional or constitutional authorization, such as the president invoking the Insurrection Act.

Key questions to ask in assessing domestic National Guard missions

The National Guard’s unique domestic mission comes with a unique responsibility to the American people. Policymakers should carefully consider what is in the best interest of the nation, states, and Guard itself when considering potential missions. Accordingly, the Statement of Principles outlines three of these overarching considerations.

Is the Guard sufficiently prepared for the mission?

National Guard members serve in a wide variety of roles, all of which require extensive training and resources. Guard deployments can range from assisting in wildfire response to supporting vaccination efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Not all potential missions can be anticipated, but policymakers should consider whether Guard units will have everything they need to successfully complete their given mission when evaluating whether a deployment is appropriate.

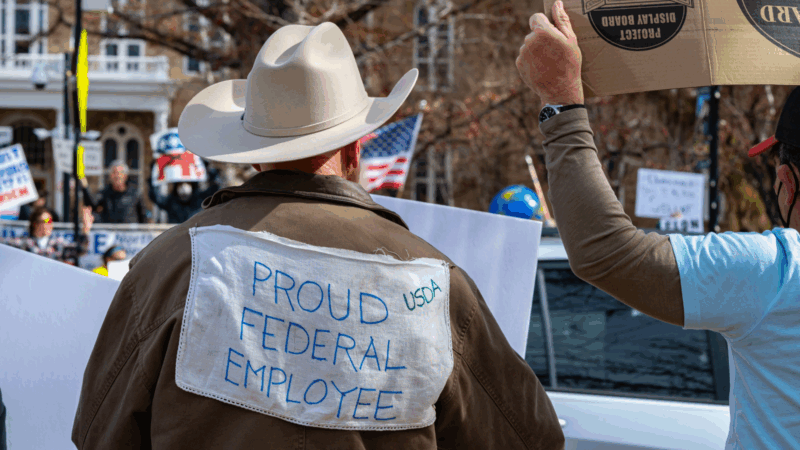

In recent years, National Guard units have increasingly been activated for missions they are not regularly trained for. In New Mexico, Guard members were asked in 2022 to work as substitute teachers because of a teacher shortage. In March 2024, New York Governor Kathy Hochul deployed 750 National Guard members to check the bags of passengers entering New York City’s subway system in response to an increase in violent crime — without giving a clear timeline or metrics for the mission’s completion. Concern over these deployments doesn’t necessarily reflect partisan viewpoints on education or public safety, and certainly doesn’t reflect a negative view of the Guard’s competency; it recognizes that completing the mission becomes more difficult as the issues the Guard is asked to address stray further and further from its core competencies.

How will the mission impact overall readiness?

Because of the National Guard’s wide purview, which includes being deployed overseas in Title 10 status, policymakers should also consider how potential domestic deployments will impact the Guard’s overall readiness. Disaster can strike at any time, and using the Guard for anything less than a genuine emergency could detract from its capacity to address catastrophes threatening life and limb. Our leaders should treat the Guard as a last resort and a resource with limits on its capacity. Consider: if a state’s National Guard is ordered to spend months on a one-off deployment, will it be ready to respond to a Category 5 hurricane or an outbreak of armed conflict abroad? To this effect, the outgoing chief of the National Guard Bureau, General Daniel Hokanson, testified in June that the Trump and Biden administrations’ deployment of National Guard members to the southern border could be deleteriously impacting military readiness. Guard members do not have unlimited time — and the time spent on nontraditional missions reduces their ability to train for the traditional functions that are the Guard’s bread and butter. Missions that substantially diverge from traditional domestic National Guard functions may sometimes be necessary, but as a general rule they should be avoided absent careful consideration of their effect on Guard readiness.

Will the mission hurt public trust in the National Guard?

The National Guard at its core doesn’t exist to serve state governors or the president, but the American people. Using its personnel for partisan political purposes undercuts that truth. Decisions to deploy the Guard should never be made to further a political agenda. When considering potential deployments on U.S. soil, policymakers should ask whether that deployment would impact the public’s trust — and that of Guard personnel themselves — in the National Guard as an apolitical institution. If some Americans come to associate the Guard with a political faction they oppose, it could weaken the Guard’s ability to respond to emergencies affecting those communities.

The National Guard at its core doesn’t exist to serve state governors or the president, but the American people. Using its personnel for partisan political purposes undercuts that truth.

This point is most salient in an election year. Any National Guard involvement in and around election administration should be limited in scope, in compliance with the law, and on the side of ensuring that every eligible voter can cast a ballot for their preferred candidates.

Every effort should be made to prevent putting Guard members in a position where their presence is opposed by other government entities or where they may be working at cross purposes with other authorities, which undermines public trust in our institutions. Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s use of the Texas National Guard to prevent U.S. Border Patrol agents from accessing parts of the southern border is a significant departure from this principle. There have been exceptional cases where such missions were warranted despite local opposition, particularly when Americans’ constitutional rights were assailed. Among several notable examples from the civil rights movement, when segregationist governors attempted to use their state Guards to prevent African American students from enrolling in segregated schools, Presidents Kennedy and Eisenhower rightfully federalized those units and ordered them to stand down. But, again, while justified, these are exceptions and not the norm.

Nobody can foresee what the rest of 2024 will bring. It’s possible that the National Guard will be needed to ensure an orderly election and transfer of power, if as a last resort. No matter what happens, these principles can be used as a roadmap for ensuring that the armed forces are used judiciously and in the best interest of the American people. Amid one of the most heated elections in recent history, it is critically important for the leaders we have elected to make decisions on our behalf to consider what is in the best interest of the nation, the states, and the Americans who serve in the Guard.

Related Content

Join Us.

Building a stronger, more resilient democracy is possible, but we can’t do it alone. Become part of the fight today.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy