Explain and contextualize the reasons why institutions

were designed as independent; the rules and norms that

have historically protected that independence; and the

consequences of politicization.

The Authoritarian Playbook

- June 15, 2022

Authoritarian takeovers rarely happen overnight. Today’s authoritarian playbook is a process that happens piecemeal and is hard to distinguish from normal political jockeying.

Our report, The Authoritarian Playbook: How reporters can contextualize and cover authoritarian threats as distinct from politics-as-usual outlines the seven fundamental tactics used by aspiring authoritarians, describes examples from in and outside the United States, and offers a framework journalists can use to differentiate between politics-as-usual and something more dangerous to democracy.

Introduction

Before the 1990s, authoritarian leaders bent on upending democracy typically came to power forcefully and swiftly, often by means of a military coup d’etat. The moment democracy ceased to exist could be time-stamped and reported on with a block headline.

Yet for at least the last 30 years, the threats to democracy have evolved. Today, democracy more often dies gradually, as the institutional, legal, and political constraints on authoritarian leaders are chipped away, one by one. This has happened, or is happening, in countries including Russia, Venezuela, Hungary, the Philippines, Poland, Nicaragua, India, Turkey — and the United States.

Want more Democracy Insights?Subscribe to our weekly newsletter

By using “salami tactics,” slicing away at democracy a sliver at a time, modern authoritarians still cement themselves in power, but they do so incrementally and gradually. Sometimes their actions are deliberate and calculated, but sometimes they are opportunistic, myopic, or even bumbling. There is no longer a singular bright line that countries cross between democracy and authoritarianism. But the outcome is still the same.

64%

Of Americans agree that democracy is in crisis and at risk of failing.

NPR/Ipsos, 2022

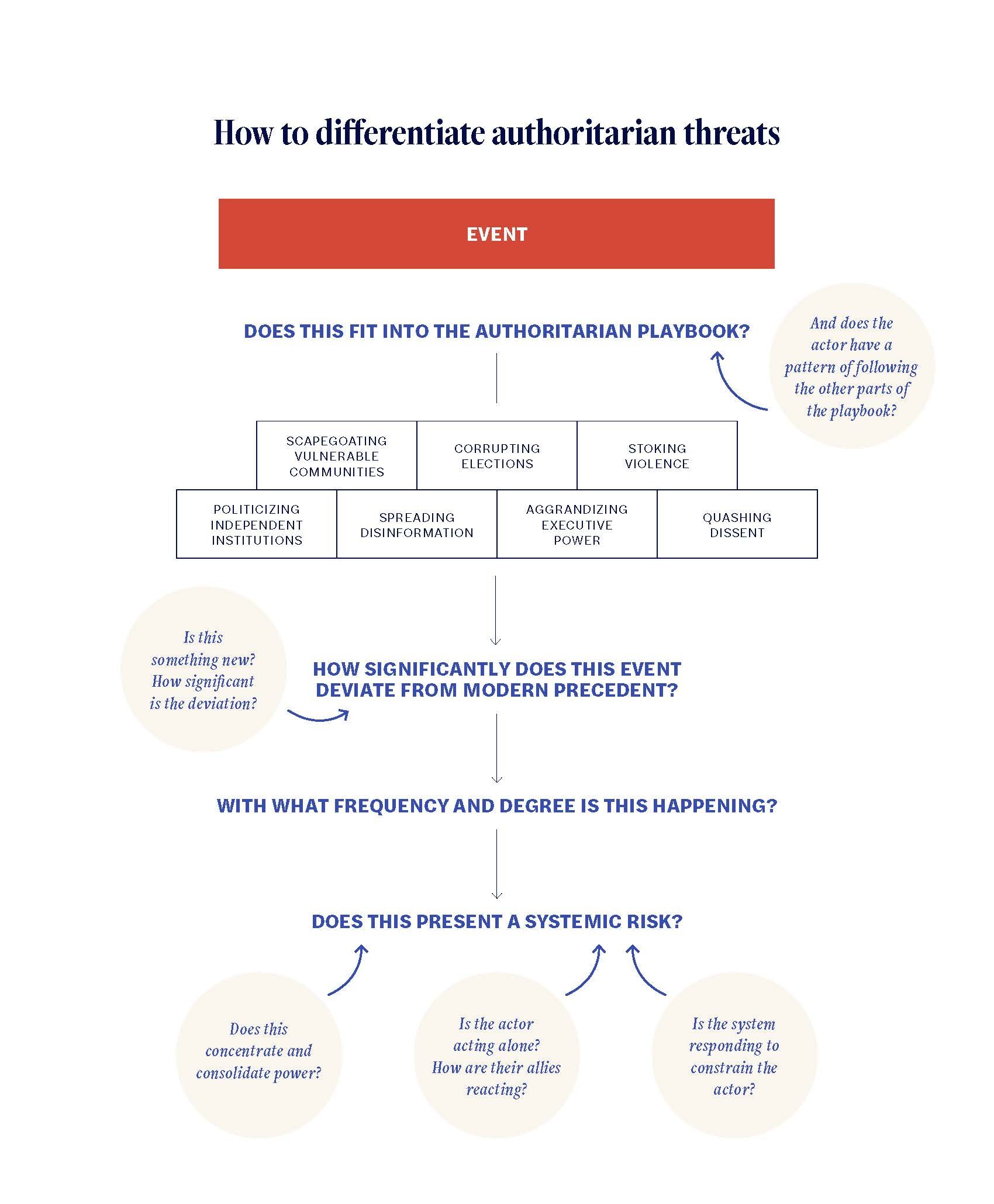

This presents a unique challenge for journalists, who are committed to providing the public much-needed information and context about important news. Contemporary democratic breakdowns are far more difficult to identify because — in snapshots — they can mimic the typical acts of political jockeying to gain advantage that are routine even in healthy democracies. But especially as these acts accumulate and intensify, hard-nosed politics can cross a line into authoritarian threats. Unfortunately, there is no simple bright-line answer or mechanical test to distinguish between the two.

At the same time, because authoritarianism worldwide tends to follow clear and consistent patterns, we can use these patterns to separate the signal from the noise. This basic framework — the authoritarian playbook — can help isolate clear and immediate dangers to democracy from partisan outrage, political hyperbole, and sensational spin.

The press has a foundational role to play in how democratic systems hold leaders accountable, and doing so requires clarity about the gravity and implications of their actions. Understanding and recognizing the authoritarian playbook as a whole can help journalists not only decide what to cover as threats to democracy, but can also help enrich and contextualize coverage about how the individual components of the playbook fit together. Americans suspect that their democracy is at risk. But by identifying and connecting individual threats to democracy to the global whole, reporting can help inform voters about more than just what is happening — it can tell them what the news means.

Covering the authoritarian danger requires that the press do two things: understand the interlocking components of the playbook itself, and distinguish between normal political jockeying and genuine authoritarian moves. This briefing is designed to help journalists do just that.

Identifying the Authoritarian Playbook

Various scholars have written extensively about how would-be authoritarians pursue power and how democratic systems backslide towards more authoritarian forms of government. Experts such as Sheri Berman, Larry Diamond, Timothy Snyder, Kim Lane Scheppele, Steven Levitsky, and Daniel Ziblatt have published some of the foremost analyses of these issues. The authoritarian playbook we present here draws on all of these insights and offers a holistic framework for understanding the interrelated tactics involved in the process.

According to these leading scholars of democracy, aspiring modern authoritarians tend to employ the same seven basic tactics in the pursuit of power.

Politicizing Independent Institutions — All democracies have functions that operate independently from partisan political actors, from law enforcement to central banking. Authoritarians attack and seek to capture those institutions. Politicizing Independent Institutions

Spreading Disinformation — Many politicians lie, but authoritarians propagate and amplify falsehoods deliberately and with abandon and ruthless efficiency. Spreading Disinformation

Aggrandizing Executive Power — Authoritarian projects cannot succeed without the cooperation or acquiescence of legislatures, courts, and other institutions. Aggrandizing Executive Power

Quashing Dissent — Strong democracies have strong oppositions and an independent press. Authoritarians seek to silence those sources of dissent. Quashing Dissent

Scapegoating Vulnerable Communities — Many authoritarians attack vulnerable groups intentionally, sowing division and attempting to turn the many against the few. Scapegoating Vulnerable Communities

Corrupting Elections — 21st-century authoritarians generally maintain the facade of elections while tilting the rules against their opponents, suppressing votes, and biasing or even overturning the results. Corrupting Elections

Stoking Violence — Most autocrats deliberately look the other way from political violence. Many actively inflame violence to stoke fear, division, and feelings of insecurity. Stoking Violence

Politicizing independent institutions

All democracies have certain functions that operate with some independence from partisan political actors. Central banking; law enforcement and courts; official statistics; financial accounting and regulation; election administration; intelligence and national security — all only work properly when appropriately protected from politics. These institutions are ripe targets for capture by autocratic factions, in whose hands they become weapons toward adversaries, shields against accountability, or, worst of all, levers of large-scale manipulation and corruption. Because of their potential to cause permanent institutional, legal, and economic damage, even early attacks on independent institutions should be treated as a substantial threat.

In the United States: Some of the most concerning attempts to politicize independent institutions have involved attacks on law enforcement — especially the U.S. Department of Justice — and election administration. As of December 2021, attempts to politicize previously independent election oversight and administration roles were underway in at least seven states. Often, overt politicization efforts are cloaked in language delegitimizing nonpartisan and professional civil service — a cornerstone of modern democracy — such as by labeling it “the deep state.”

Suggestions for journalists

Rely on experts familiar with each institution’s

history, including former appointed officials.

Spreading Disinformation

Spreading disinformation

All politicians engage in spin, and many outright lie (at least occasionally). But authoritarians propagate and amplify falsehoods with abandon and ruthless efficiency. Often, this disinformation is spread through coordinated networks, channels, and ecosystems, including politically aligned or state-owned media. These lies have two purposes: First, they are political weapons aimed at crippling opponents and shoring up key constituencies through false grievances. And second, they are smokescreens for power grabs and abuses, insulating authoritarians against accountability by sowing doubt and confusion. The goal is not always to sell a lie, but instead to undermine the notion that anything in particular is true.

In the United States: Disinformation is a unique challenge for the United States today, as authoritarian actors have taken advantage of our strong First Amendment tradition and fragmenting online information ecosystem. As a result, over one-third of Americans believe the Big Lie — a coordinated disinformation campaign falsely claiming the 2020 election was stolen. These lies, and the false sense of grievance they are designed to inspire, are almost certain to drive authoritarian attitudes for years to come. And in the short-term, the Big Lie is being used as cover to rewrite election laws and lay the groundwork for potential future power grabs.

Suggestions for journalists

Beware of the illusory truth effect, wherein disinformation can be inadvertently spread by stories that aim to debunk it. Impressions of truth come from hearing repeated claims, regardless of context.

Strictly avoid headlines that repeat false claims, even if contextualized, as disinformation spreads best through momentary impressions.

Cover disinformation as a story, not just a statement. Investigate and illuminate the systems, motives, funding, mechanisms, and actors spreading lies.

Aggrandizing Executive Power

Aggrandizing executive power; weakening checks and balances

Authoritarian projects cannot succeed without the cooperation or acquiescence of legislatures, courts, and other institutions designed to provide checks and balances. In some cases, authoritarians explicitly rewrite the rules to strengthen executive power and weaken legislatures, while in others they simply stack these competing institutions with lackeys and compliant allies. Authoritarians also often justify the expansion of executive power with cults of personality and aggrandizement of the trappings of office, while denigrating checks and balances as corrupt obstacles to the popular will.

In the United States: A particular puzzle in the United States is how to distinguish genuinely authoritarian aggrandizement of executive power from the decades-long and bipartisan trends towards expanding presidential authority and valorizing the presidency. Some historical cases have been fairly clear. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt attempted to circumvent the Supreme Court’s opposition to his New Deal legislation by expanding the Court from nine members to 15, the effort was rejected even by members of his own party. When the administration of Ronald Reagan subverted congressional restrictions on support to Nicaraguan rebels in the Iran-Contra Affair, the legislative branch was quick to defend its prerogatives. But while such examples reflect how the too-easily abused powers of the president have been exploited over decades by both parties, the Trump administration took this to new heights. Trump especially embraced emergency powers, pardons, and acting appointments while ignoring congressional subpoenas and spending appropriations, rejecting legislative oversight, and claiming immunity from judicial accountability.

Suggestions for journalists

Provide context on the role of the executive branch in the governing process in relation to other branches and centers of power, such as the legislature, judiciary, and state governments.

Avoid political intrigue stories that can, by overstating process dysfunction and conflicts, inadvertently help warm voters to executive power grabs.

Quashing Dissent

Quashing criticism or dissent

Strong democracies have strong oppositions and an independent press that alerts the public when those in power are abusing their positions. Autocratic movements and regimes tend to weaken not only freedom of speech and of the press, but also the influence of public voices (often media or civil society) that could serve as vocal counterpoints to the autocratic faction. In Hungary, for example, powerful allies of Viktor Orbán used their economic muscle to buy up and consolidate the vast majority of independent media, essentially making criticism of the ruling party, Fidesz, financially unviable. Multiple autocrats around the world have adopted the cry “fake news” as a way to delegitimize critical coverage. And while newsrooms are a favorite target, whistleblowers, civil society, activists, and religious leaders also regularly face attacks, jail time, and worse.

In the United States: The U.S. has a long tradition of independent media and vibrant dissent. And while the Trump administration’s antagonistic relationship with reporters was well documented, the former president went beyond the typical back-and-forth with a critical press corps. He used, or threatened to use, the regulatory and enforcement powers of the state to punish the speech of journalists in at least four ways: initiating a government review to raise postal rates to punish the owner of the Washington Post; directing DOJ enforcement actions against media companies, including CNN’s parent company; interfering with White House press access; and threatening to revoke broadcast licenses.

Criticism and dissent can come from many sectors, not just civil society or the press. Government whistleblowers who report wrongdoing enjoy legal protection in America, but like authoritarian leaders the world over, Trump demonstrated little tolerance for internal dissent. In an attempt to obstruct accountability for his abuse of power, Trump and his allies used intimidation and retaliatory attacks against Lt. Col. Alexander Vindman to try to prevent him (and scare off others) from testifying before Congress during impeachment proceedings, then to punish him for doing so.

More recently, several states have introduced or passed new laws, like Florida’s “anti-riot” bill, that increase criminal penalties for protestors in the vicinity of demonstrations that turn violent. Restricting civil society’s ability to mobilize dissent is a glaring indicator of democratic backsliding. There have also been — although to a far lesser degree — proposed laws that attempt to criminalize disinformation, but in a way that violates fundamental rights.

Suggestions for journalists

Pay attention to proposed policy solutions that adopt overbroad standards and fail to consider whether targeted activities are protected fundamental rights.

Be especially wary of efforts to silence dissent within federal, state, and local public institutions, including universities and bureaucracies.

Scapegoating vulnerable communities

Democracy in diverse societies depends on protecting the rights of minorities. This includes political minorities who have lost at the ballot box and groups who identify as different from traditionally dominant majoritarian groups along the lines of race, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Research has shown that robust social ties reduce the effectiveness of repression. Therefore, modern-day autocrats use demographic identity as a way to sow division. This tactic also allows autocrats to claim a broad mandate after coming to power with only plurality support. Authoritarian parties in Hungary and Poland — while ascending to power with only plurality support — have demonized immigrants and used claims of representing “the real Poles” or “the real Hungarians” as ways of establishing a more legitimate popular mandate. As globalization and looser borders force many nations to grapple with questions about national identity, immigrants and refugees have been the targets of far-right populist parties across many backsliding democracies, including the United States.

In the United States: Of course, drawing a hard line between differences in ideological or cultural beliefs, and the scapegoating of specific groups, can be difficult. That said, autocrats tend to explicitly reject any benefits of pluralism or diverse societies. They employ political strategies that target minorities in a way that energizes and reinforces solidarity among their supporters. In the United States, where Black Americans have been marginalized for centuries, the language and rhetoric around voter fraud often nods to this history of racialized politics. But it’s not just about wielding culturally divisive “wedge” issues as political strategy: Authoritarians use state power to target and infringe on minority rights, from Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ limiting of consent decrees, to the rolling back of Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) and the exempting of certain lenders from the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. More recently, in the last year in Texas, more than 40 bills were introduced that would curb the rights of transgender people.

Suggestions for journalists

Avoid narratives that present conflicts between powerful majority groups and more marginalized groups as equal or balanced.

Refrain from unnecessarily amplifying political rhetoric targeted at vulnerable communities.

Corrupting Elections

Corrupting elections

The biggest innovation of 21st-century authoritarians has been to maintain the facade of democratic elections, while at the same time tilting the rules against their opponents. They do this by suppressing votes and biasing, distorting, falsifying, or even overturning the results — either through capturing the referees or by manipulating the electoral rules in their favor.

In the United States: Even in the face of perhaps the “most secure election in U.S. history,” the integrity and structural features of elections in the U.S. are being tested. We now know an effort to block the certification of the 2020 election results involved coordination among state and local officials, and former president Trump and his advisors. Since 2020, at least 19 states have passed election-law changes that both reduce ballot access, and provide more opportunities for partisan interference in the vote-counting and certification process.

Suggestions for journalists

Explain existing election processes and safeguards. Often, those who attempt to corrupt elections justify their actions by claiming that elections are insecure or vulnerable to fraud.

Center election officials and nonpartisan experts. Stories that primarily quote partisan actors — including election lawyers — can contribute to false impressions that elections are already partisan.

Stoking violence

Finally, while healthy democratic actors always eschew civil violence, autocrats either deliberately look the other way or even intentionally inflame politically useful violence. Such outbreaks can offer political cover for restrictions on civil liberties or the expansion of coercive security measures. They can also suppress voter turnout among opposition and inspire supporters to turn out in competitive areas.

Stoking violence advances authoritarian efforts in other areas of the playbook such as quashing dissent, but it also undermines the norms and trust among political elites, as well as the broader population, that underpin democratic stability. As feelings of insecurity rise, social divisions become more salient and politicized, and political leaders’ incentives shift further toward hardball politics over negotiation and compromise.

In the United States: The history of the United States includes plenty of violent episodes, particularly around elections and campaigns, as exemplified by years of violent intimidation of Black voters in the South. Recent decades have seen far fewer episodes of political violence, but recently this trend has reversed: Between 2020 and 2021, there were over 1,200 events categorized as political violence in the United States, resulting in more than 150 deaths. The number of hate crimes reported to the FBI rose 41 percent between 2015 and 2020. International observers have expressed deep concern about the tone of American political campaigns and the way it raises the risk of violence related to election outcomes. These trends culminated in the January 6 insurrection, in which a violent mob stormed the U.S. Capitol, attempting to disrupt the lawful transfer of executive power following the 2020 election. Five deaths were attributed to the violence on that day, and 140 police officers were injured. Yet the alignment of some political leaders with violent actors, and the refusal of others to condemn violence, contribute to a perception of impunity. This kind of violence both results from and contributes to declines in democratic norms and values.

Suggestions for journalists

Remain attentive to how political leaders’ statements are received by violent actors. Politicians may offer statements with multiple messages, but the way those messages are understood matters.

Avoid sensationalizing violent events and inflating risk perceptions.

Related Content

It can happen here.

We can stop it.

Defeating authoritarianism is going to take all of us. Everyone and every institution has a role to play. Together, we can protect democracy.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy