A Democracy Crisis in the Making

- December 7, 2023

Introduction

As the 2024 election approaches, state legislatures continue to propose and enact laws that expose our election system to partisan disruption and manipulation. These laws ultimately increase the risk of subversion — that is, a declared outcome that does not reflect the true choice of the voters. They also abandon long-standing principles of nonpartisan election administration and instead allow for — or even encourage — dysfunction, misinformation, confusion, or manipulation by partisan actors.

Our organizations have been tracking this trend for three years, since the 2020 election. In that time, state legislatures have introduced more than 600 of these bills, and 62 have become law in 28 states. As we noted in our Report earlier this year, the 2022 elections were largely successful and free of serious subversion efforts. But we remain concerned that recently enacted laws could help precipitate a crisis — particularly in an election involving a candidate at the top of the ticket who has already attempted to subvert an election. At the very least, these laws will make it harder for professional election administrators, who already face a rise in unjustified suspicion and unprecedented levels of harassment, to do their jobs on behalf of our democracy.

This year-end update to our June 2023 Report reviews some of the major developments that we have seen this year. Some states warrant particular attention. In North Carolina, a legislative supermajority has engineered a host of changes in election oversight that could open the door to partisan interference, confusion at the polls, gridlock during the certification process, or doubt about the results, in addition to disinformation at each of those steps. In Texas, two laws enacted this year targeted the state’s most populous and diverse county, abolishing the county election office and empowering the state to take control over election procedures under flimsy pretexts and with partisan motives. In Wisconsin, some legislators, relying in part on baseless conspiracy theories, have repeatedly sought to remove the state’s top nonpartisan election official, so far without success.

Hand in hand with these legislative changes, anti-democracy actors are engaged in acts outside statehouses that could subvert elections through other means. In jurisdictions across the country, local officials are pushing to have ballots counted exclusively by hand, a method all but guaranteed to cause delay, expense, and inaccuracy, particularly in populous election jurisdictions. Driven by baseless election conspiracy theories, nine states have withdrawn from the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), a membership organization that helps state election officials maintain accurate voter rolls and prevent illegal voting. And election officials across the country, who have been subjected to three years of harassment and intimidation grounded in lies about the 2020 election, will continue to face challenges in 2024, including the emergence of artificial intelligence and persistent mis- and disinformation. At the same time, the departure of experienced election officials may increase the risk of errors in election administration and contribute to fueling conspiracy theories and pretexts for subversion efforts. In addition, some states have yet to adjust their laws to conform with the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022, a bipartisan, federal response to former President Trump’s attempt to overturn the will of the voters in the last presidential election.

In this end-of-year memorandum, we assess each of these obstacles to the professional, nonpartisan administration of a free, fair, and secure 2024 election.

Legislative Year in ReviewLegislative Year in Review

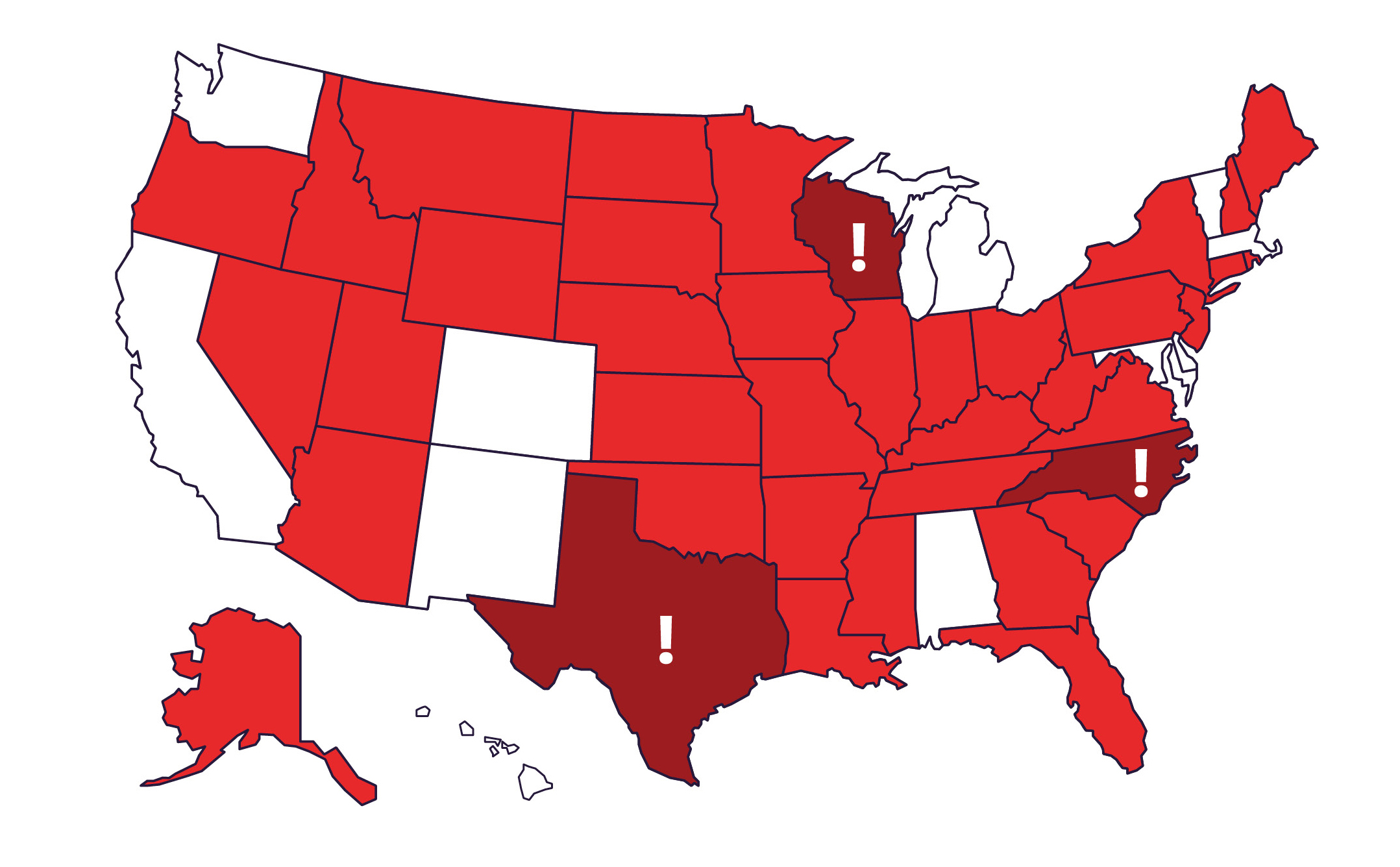

All told, in the 2023 legislative cycle, we identified 196 bills that were introduced in 39 states that would interfere with election administration. Ultimately, 21 of those bills became law across 15 states, while 7 bills were vetoed across 2 states.

At the time of this update, the overwhelming majority of state legislative sessions have adjourned. We have identified the following number of bills for each of the five subversion categories we catalog1A bill can be cataloged in multiple subversion categories. For an in-depth description of the subversion categories, see The States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward, A Democracy Crisis in the Making Report: 2024 Election Threats Emerging, (June 8, 2023): 5, https://statesuniteddemocracy.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/DCIM2023.pdf.:

- Seek to usurp control over election results: 4 BILLS. These bills would give legislators or other state officials direct control over election outcomes.

- Require partisan or unprofessional election “audits” or reviews: 26 BILLS. These bills create amorphous post-election review schemes outside the professional standards of traditional election audits that could promote subversion and needlessly call election outcomes into doubt.

- Seize power over election responsibilities: 34 BILLS. These bills would shift election administration responsibilities away from professional, nonpartisan officials and toward partisan actors in the legislature.

- Create unworkable burdens in election administration: 109 BILLS. These bills would interfere with the basic procedures of election administration, increasing the risk of chaos and delay and enabling specious claims of irregularity that could be a pretext for subversion.

- Impose disproportionate criminal or other penalties: 76 BILLS. These bills would create or expand penalties for election officials in the ordinary execution of their jobs, including criminalizing inadvertent mistakes.

Of note amongst the newly identified bills and resolutions since our June 2023 Report are the developments in North Carolina, which are detailed below in Section 3(a). We also note the continued trend of prohibiting external election administration funding, which we have highlighted in our past reports. This country’s election infrastructure has been plagued by chronic underfunding2Election Infrastructure Initiative, 50 States of Need: How We Can Fully Fund Our State and Local Election Infrastructure, (2022), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6083502fc0f6531f14d6e929/t/61f836e405feca3722d63b9d/1643656990641/50-States-Of-Need.pdf.. Outright bans, when not paired with increased state or federal investments in elections, contribute to an increased risk of crises because elections are harder to administer without proper funding for voting equipment and personnel. Since the release of our June Report, Wisconsin has continued its quest to ban private philanthropic donations for nonpartisan election administration, with the introduction of S.J.R. 78 and A.J.R. 77. Legislators introduced A.B. 5385 in New Jersey and S.B. 753 in Maine, where the bans on private donations are enforced by potential felony charges. Also introduced in Maine was S.B. 730, which requires the legislature to approve election officials’ receipt of federal funding for election administration.

Legislative Election Subversion Hotspots

A. North Carolina

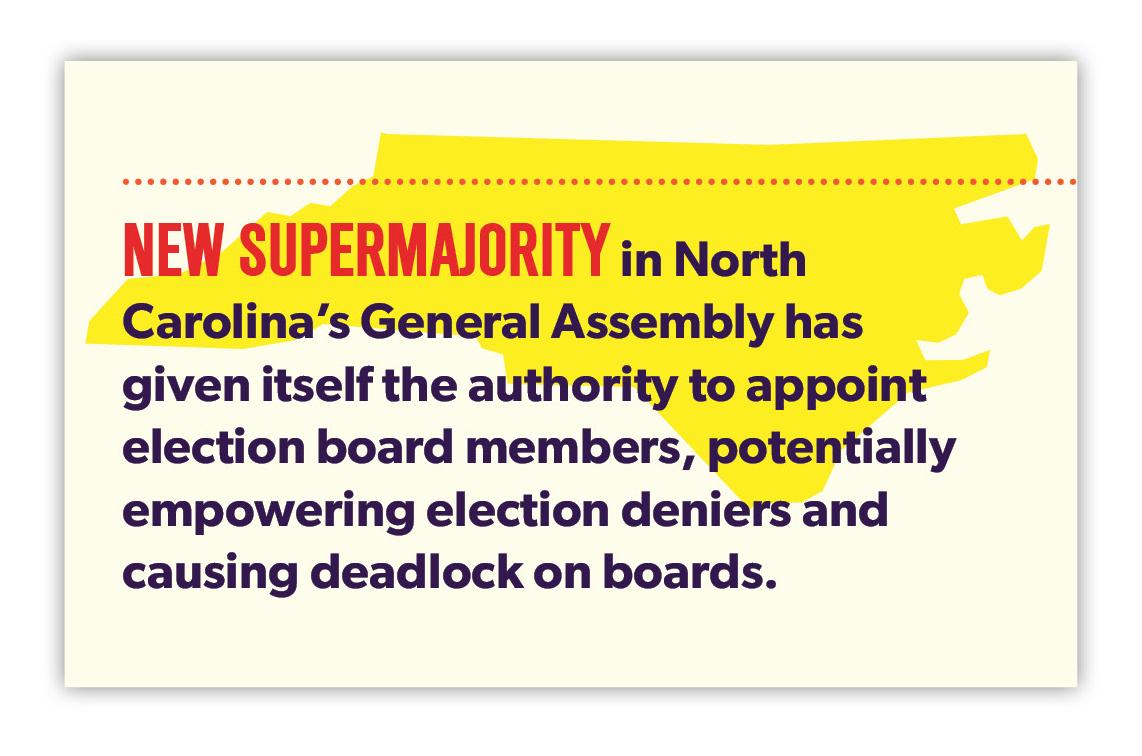

In April 2023, a recently elected North Carolina representative switched her party affiliation from Democrat to Republican3Nick Corasaniti and Neil Vigdor, “Democrat’s U-Turn to Join the G.O.P. Upends North Carolina Politics,” New York Times, Apr. 5, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/05/us/politics/tricia-cotham-north-carolina.html., which gave election deniers in the statehouse more power in both chambers of the General Assembly4Kyle Ingram, “After meeting with ex-Trump lawyer, GOP pitches new NC voting rules vetoed by Cooper,” The News and Observers, June 21, 2023, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/election/article275979931.html.. This new supermajority went on to pass legislation that dramatically shifted election administration in the state, creating new sources of confusion and potential chaos during elections.

North Carolina’s General Assembly gave itself significant control over election administration by substantially changing the makeup of election boards. Overriding a gubernatorial veto, the General Assembly passed S.B. 749, N.C. Session Law 2023-139, which established new state and county level elections boards appointed entirely by the General Assembly. While the boards will have even numbers of appointees from each major party, the law makes no provision for how to resolve a deadlock, including on ballot challenges and certification issues. Previously, the Governor appointed the State Board of Elections and that Board appointed the county boards, with the Governor’s party maintaining a one-member majority on each board. In addition, with the General Assembly in charge of appointments, the state could see as many as 408 new elections officials — four for each of the state’s 100 counties and eight on the State Board of Elections. This change could introduce numerous new officials into the process, some of whom may lack previous election experience, into a pivotal election cycle.

This new law is not without precedent. In 2016, the General Assembly passed legislation that abolished the existing election board and constituted a new board, which the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down for violating separation of powers5Cooper v. Berger, 370 N.C. 59 (2017) (striking down the bills for encroaching on the governor’s ability to faithfully execute the laws).. After losing in court, the General Assembly then sent the issue to the voters via a constitutional amendment in 2018, which the voters rejected by 62 percent6Ari Berman, “North Carolina Republicans Just Passed a Massive Power Grab to Seize Control of Elections,” Mother Jones, Sept. 22, 2023, https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2023/09/north-carolina-election-boards-bill-roy-cooper/.. Now, in 2023, Governor Cooper has filed a lawsuit challenging this new law that will test whether the new conservative majority on the North Carolina Supreme Court will let this assertion of legislative dominance stand7“Governor Files Lawsuit to Overturn Unconstitutional GOP Elections Board Bill” North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, Oct. 17, 2023, https://governor.nc.gov/news/press-releases/2023/10/17/governor-files-lawsuit-overturn-unconstitutional-gop-elections-board-bill#:~:text=The%20Governor%27s%20lawsuit%20explains%20that,of%20that%20power%20for%20itself.

New administrative burdens on North Carolina’s elections officials in next year’s elections will also be substantial, thanks to the enactment of S.B. 747, N.C. Session Law 2023-140, after an override of the governor’s veto. This law tasks elections officers with, for example, logging the time of entry and signature of all adults entering voting locations, including those assisting elderly or disabled voters; logging and reporting the types of identification used by both in-person and mail voters; reporting segregated absentee and early voting tallies throughout the early voting period; and expanded voter list maintenance efforts. This new law also makes same-day registration more cumbersome and subject to post-election verification procedures that could give rise to disputed vote tallies, and the law extends the period for absentee vote challenges through five days post-election. At the same time, after protracted legal battles, North Carolina is also now implementing voter ID provisions that are among the strictest in the country, which election officials will have to implement alongside this new law’s requirements.

In 2024, North Carolinians will also see newly empowered partisan “observers” at voting sites. These observers, appointed by county political party chairs, may take notes, including about individual voters; listen in on conversations between voters and election administrators; obtain lists from election officials at least three times per day of who has voted; move freely about the voting location; and take photos of voting locations before they open and after they close. People serving as observers need not have any experience in election administration, which creates an opening for them to sow doubt or confusion and spread misinformation about election administration procedures8Rusty Jacobs, “‘Election integrity’ push in NC has ties to Trump’s efforts to overturn 2020 presidential race,” WUNC, Aug. 23, 2023, https://www.wunc.org/politics/2023-08-23/election-integrity-push-in-nc-has-ties-to-trumps-efforts-to-overturn-2020-presidential-race; Rusty Jacobs, “Voting in North Carolina faces some big changes with a Republican-backed bill,” NPR, Sept. 2, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/09/02/1197252802/north-carolina-voting-legislation; Rusty Jacobs, “State elections board to consider changing rules for partisan poll observers,” WUNC, Aug. 10, 2022, https://www.wunc.org/news/2022-08-10/state-elections-board-to-consider-changing-rules-for-partisan-poll-observers..

While some of these statutory changes may have plausible policy justifications, their cumulative effect may inject uncertainty and opportunities for dis- and misinformation into the election cycle. Legal challenges to both laws may mitigate or alter some of the more concerning provisions, but late-breaking decisions themselves could cause confusion for election officials and voters alike9Kyle Ingram and Dawn Baumgartner Vaughan, “NC GOP overturns 5 Cooper vetoes, as top Democrat accuses them of ‘creating a monster,’” The News & Observer, Oct. 11, 2023, https://www.newsobserver.com/news/politics-government/article280300589.html; Gary Robertson, “North Carolina’s governor sues lawmakers for a measure that eliminates his elections board authority,” The Associated Press, Oct. 17, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/north-carolina-elections-registration-lawsuit-2068ad9329c59d091e5e17fb4e880cc2..

B. Texas

As emphasized in previous reports, Texas remains at high risk of election subversion because its legislature, Governor, and Attorney General all share a penchant for election denialism, and have collectively laid a foundation that threatens efficient and effective election administration in the state10A Democracy Crisis in the Making Report: 2024 Election Threats Emerging, supra n. 1, at 12, 15, 25.. Our June 2023 Report outlined several types of threats to free and fair elections in Texas that are worth re-examining as the year comes to a close11Ibid. at 12..

This summer, Texas enacted two alarming laws specifically targeting Harris County (based on population thresholds set in the bills). Harris County is home to Houston, has over 2,500,000 registered voters, and a large share of the state’s registered Democratic voters12“Harris County Voter Registration Figures,” Texas Secretary of State, accessed Nov. 20, 2023, https://www.sos.state.tx.us/elections/historical/harris.shtml.. The first of these bills, S.B. 1750, abolished the Harris County election administrator’s office, transferring its duties to the county tax assessor and county clerk, and away from the election administrator and staff specifically trained and prepared to administer elections13Harris County filed a lawsuit alleging that this precise targeting was illegal. The Texas State Supreme Court allowed to remain in effect through the 2023 election cycle and slated the case for further consideration in late November. See Tom Abrahams, “Harris Co. election administrator is jobless after TX Supreme Court rules Senate Bill 1750 into law,” ABC Eyewitness News, Aug. 22, 2023, https://abc13.com/senate-bill-1750-harris-county-politics-houston-elections-area-politicians/13685768/.. Harris County filed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of S.B. 175014Natalia Contreras, “Harris County’s election chief remains in legal limbo after judge rules that lawmakers can’t dissolve the position,” The Texas Tribune, Aug. 15, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/08/15/harris-county-elections-changes-ruling/. Harris County ultimately dropped the lawsuit, with the county attorney calling the case “moot” because the county was required to comply with the law as of September 1, 2023. Jen Rice, “Harris County drops lawsuit challenging new state law that eliminated its election office,” Houston Chronicle, Nov. 24, 2023, https://www.houstonchronicle.com/politics/houston/article/harris-county-drops-lawsuit-18510850.php.. This law, which was opposed by election officials, threatens to harm elections in the state’s most populous county by opening gaps between the voter registration and elections processes that were closed when both functions were housed in one office and by confusing voters over which office to turn to when they have time sensitive, and sometimes complicated, election questions15Natalia Contreras, “Harris County must remove its elections chief under new legislation headed to Gov. Greg Abbott,” The Texas Tribune, May 23, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/05/23/texas-legislature-harris-county-elections/..

The second law targeting Harris County, S.B. 1933, empowers the Secretary of State to conduct “administrative oversight” of a county election office if a complaint is filed against the office (including by candidates or party chairs). If the Secretary of State deems oversight necessary, the office will be required to seek approval for “any policies or procedures” related to election administration and the Secretary can remove the administrator if they determine a “recurring problem” was not sufficiently rectified16S.B. 1933, 88th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Tex. 2023).. S.B. 1933 paves the way for potential control of the county’s elections by a partisan state official. Perhaps foreshadowing this potential takeover, the Secretary of State, in an October 19, 2023 press release regarding the audit of Harris County’s 2022 midterm elections, referenced the oversight power of S.B. 1933 and invited the public to submit complaints17“Secretary Nelson Releases Harris County Audit Preliminary Findings,” Texas Secretary of State, Oct. 19, 2023, https://www.sos.state.tx.us/about/newsreleases/2023/101923.shtml.. A third law of concern is H.B. 5180, which creates a new administrative burden by requiring all cast ballots to be made publicly available within 61 days of the election (when previously the law required public disclosure at 22 months)18Tex. Elec. Code § 66.058 (2017).. Publicizing ballot images could also fuel disinformation by election skeptics conducting their own “audits” or inspections of election results19Ballots were previously available to the public for inspection within 22 months of the election. This new law dramatically cuts that timeline. See H.B. 5180, 88th Leg., Reg. Sess. (Tex. 2023)..

In our June Report, we highlighted several instances of Texas county election officials stepping down amidst unworkable new expectations and election denialism-fueled harassment20A Democracy Crisis in the Making Report: 2024 Election Threats Emerging, supra n. 1, at 25.. Since then, several officials in Kerr County have also resigned in response to a disinformation-fueled push to hand count all ballots and eliminate electronic equipment, which would hamper effective and efficient election administration in the county21Natalia Contreras, “Distrust of voting machines throws a Texas county’s election planning into chaos,” The Texas Tribune, Oct. 13, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/10/13/kerr-county-voting-machine/.. The current interim election official, who will administer the 2024 cycle, has not overseen elections in more than a decade. On a brighter note, election official staffing has started to stabilize in other counties. Gillespie County hired a new election administrator in August 2023, a full year after the entire election administration staff resigned22Brent Burgess, “Riley hired as new county elections administrator,” Fredericksburg Standard-Radio

Post, Aug. 16, 2023, https://www.fredericksburgstandard.com/2023/08/16/riley-hired-new-county-elections-administrator/.. Hood County also hired someone to replace its experienced director who resigned in the wake of post-2020 election harassment23Kathy Cruz, “Commission chooses new elections director,” Hood County News, Nov. 19, 2021, https://www.hcnews.com/stories/commission-chooses-new-elections-director,5897?.. Heider Garcia, Tarrant County’s former elections official who resigned after experiencing partisan pressure, will take the reins as Dallas County’s new elections administrator24Natalia Contreras, “Heider Garcia, celebrated elections chief from Tarrant County, set to run elections in Dallas,” Texas Tribune, Oct. 18, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/10/18/heider-garcia-dallas-county/.. Garcia has committed to conducting nonpartisan and professional elections in Dallas County, the state’s second most populous county25Ibid..

Absent special sessions, the Texas legislature will not convene again until 2025. Meanwhile, Harris County officials will be administering the 2024 election under the threat of potential takeover by the state.

Election Issues on the 2024 HorizonElection Issues on the 2024 Horizon

Heading into 2024, we are keeping a close eye on several trends that threaten to undermine effective election administration. Election deniers and their allies continue to advocate for eliminating voting machines and instead exclusively hand counting ballots and abandoning the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC). Election offices continue to face funding shortfalls, high staff and leadership turnover, disinformation (including campaigns bolstered by AI-generated content), and threats to their safety. States are at varying stages of preparing for compliance with the new deadlines under the federal Electoral Count Reform Act, which was enacted with bipartisan support and aimed at preventing election subversion at future January 6 Joint Sessions of Congress. We examine these issues each in turn.

A. Hand Counting All Ballots: A Recipe for Delay and Inaccuracy

Despite the time-tested accuracy and efficiency of voting machines and evidence that hand counting all ballots is much slower and far less accurate than counting ballots by machine, activists continue to push for a reversion to exclusively hand counting ballots in the name of “election integrity.”26National Task Force on Election Crises, Hand-Counting Ballots Introduces Unnecessary Risks and Costs to Elections, (Aug. 2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e70e52c7c72720ed714313f/t/64dbdb9711ced1105fda6d0a/1692130199642/23.08.15-NTFEC-Hand-Counting-Explainer.pdf; Barry Burden, “Paper ballots are good, but accurately hand-counting them all is next to impossible,” Fox59, Sept. 10, 2023, https://fox59.com/news/national-world/paper-ballots-are-good-but-accurately-hand-counting-them-all-is-next-to-impossible/. These activists, fueled by election deniers, their allies, and supporters in the media, object to the use of voting machines to tally the votes27 Alexandra Ulmer and Nathan Layne, “Trump allies breach U.S. voting systems in search of 2020 fraud ‘evidence’,” Reuters, Apr. 28, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/usa-election-breaches; Verified Voting, Voting Equipment Database, (Oct. 15, 2020), https://verifiedvoting.org/equipmentdb/; David Folkenflik and Mary Yang, “Fox News settles blockbuster defamation lawsuit with Dominion Voting Systems,” NPR, Apr. 18, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/04/18/1170339114/fox-news-settles-blockbuster-defamation-lawsuit-with-dominion-voting-systems; Robert Anglen and Ryan Randazzo, “Previously hidden Cyber Ninjas texts revealed in Republic records lawsuit over ‘audit’,” Arizona Republic, Oct. 24, 2023, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/previously-hidden-cyber-ninjas-texts-revealed-in-republic-records-lawsuit-over-audit/ar-AA1iJ3VS; Holly Ramer and Christina Cassidy, “Some in GOP want ballots to be counted by hand, not machines,” The Associated Press, Mar. 12, 2022, https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/politics/previously-hidden-cyber-ninjas-texts-revealed-in-republic-records-lawsuit-over-audit/ar-AA1iJ3VS.. These voting machine technologies have existed for years — nearly a century in the case of optical scan — and studies consistently show they make the process of counting ballots faster and more accurate28Sam Oliker-Friedland, The Push for Hand Counting: A Step Back in Responsible Election Practices (Democracy Docket, Sept. 7, 2023), https://www.democracydocket.com/opinion/the-push-for-hand-counting-a-step-back-in-responsible-election-practice; Colleen Leahy, “What we know about hand counting ballots,” WPR, Sept. 29, 2023, https://www.wpr.org/listen/2122401; Alice Clapman and Ben Goldstein, Hand-Counting Ballots: A Proven Bad Idea (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, Nov. 23, 2022), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/hand-counting-votes-proven-bad-idea.. Machines provide an efficient and scalable baseline for vote counting and undergo significant testing before and after elections to ensure their accuracy29Karena Phan and Ali Swenson, “Why do elections experts oppose hand-counting ballots,” The Associated Press, Nov. 3, 2022, https://apnews.com/article/2022-midterm-elections-nevada-83f8f680cfaf96adce39bcbdd8e4610a..

Since at least 2000, there have been debates over the accuracy and veracity of our elections in this country. While the machines are not flawless, until recently, there was a consensus in favor of utilizing tested and proven technologies to improve election administration, not returning to inferior methods from the past30“Election Security,” Brennan Center for Justice, accessed Nov. 14, 2023, https://www.brennancenter.org/election-security; “Voting Technology,” MIT Election Data + Science Lab, Apr. 21, 2023, https://electionlab.mit.edu/research/voting-technology..

Hand counts have a limited and appropriate place in election administration, such as in very small jurisdictions or as part of the recount or post-election audit procedure31Oliker-Friedland, supra n. 28.. But studies and experience show that scaling up the use of hand counts leads to unacceptable delay, expense, and inaccuracy32Stephen Ansolabehere and Andrew Reeves, “Using Recounts to Measure the Accuracy of Vote Tabulations: Evidence from New Hampshire Elections, 1946-2002,” in Confirming Elections: Creating Confidence and Integrity Through Election Auditing, ed. R. Michael Alvarez, et al. (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012); Stephen Goggin, et al., “Post-Election Auditing: Effects of Procedure and Ballot Type on Manual Counting Accuracy, Efficiency, and Auditor Satisfaction and Confidence,” Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 11 no. 1 (Mar. 5, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2010.0098; Daniel Garteneberg, et al., “Examining the Role of Task Requirements in the Magnitude of the Vigilance Decrement,” Frontiers in Psychology 9 (Aug. 20, 2018), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01504; Zach Montellaro, “Trump backers push election change that would make counting slower, costlier and less accurate,” Politico, Mar. 26, 2022, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/03/26/trump-allies-elections-vote-counting-00020574; Beth Reinhard and Yvonne Wingate Sanchez, “As more states create election integrity units, Arizona is a cautionary tale,” Washington Post, Sept. 26, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/2022/09/26/arizona-election-integrity-unit/; Oliker-Friedland, supra n. 28.. A 2018 study of Wisconsin elections in 2011 and 2016 found that machines counted ballots more accurately than humans counting by hand33Stephen Ansolabehere et al., “Learning from Recounts,” Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 17 no. 2 (June 1, 2018): 100-116, https://doi.org/10.1089/elj.2017.0440.. Nevertheless, the push for full hand counts continues around the country34Alice Herman, “Wisconsin voters caught in the middle as misinformation takes on education,” The Guardian, Sept. 3, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/sep/03/education-v-misinformation-opposing-groups-duel-for-wisconsin-voters-attention.. In Mohave County, Arizona, a more recent test run of ballot hand counting proved so slow and error-prone that the Board of Supervisors ultimately voted not to require hand counting in August and again when the issue resurfaced in November35Sasha Hupka, “Mohave County was promised volunteers and a lawyer. It still won’t hand count ballots,” Arizona Republic, Nov. 20, 2023, https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2023/11/20/mohave-county-supervisors-vote-for-2nd-time-hand-counting-ballots-in-2024/71652673007/.. Municipalities in California, Georgia, and Nevada have engaged in hand counting and found it created similar major delays36National Task Force on Election Crises, supra n. 26; Oliker-Friedland, supra n. 28..

As a result, California for example, passed a bill restricting hand counting to very small jurisdictions37Nicholas Kerr, “Bill limiting ballot hand counting in California becomes law; one county pledges to defy statute,” ABC News, Oct. 4, 2023, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/bill-limiting-ballot-hand-counting-california-law-county/story?id=103741610.. Election experts make a convincing case that common sense reforms and real investment in our election infrastructure, not hand count requirements, will lead to improved accuracy and confidence in election results38Derek Tisler and Lawrence Norden, Securing the 2024 Election (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, Apr. 27, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/policy-solutions/securing-2024-election.. To be sure, there is still a role for hand counting as part of the election audit process, but in the United States at large, the “hand count only movement” would be a source of new challenges for efficient and accurate election administration.

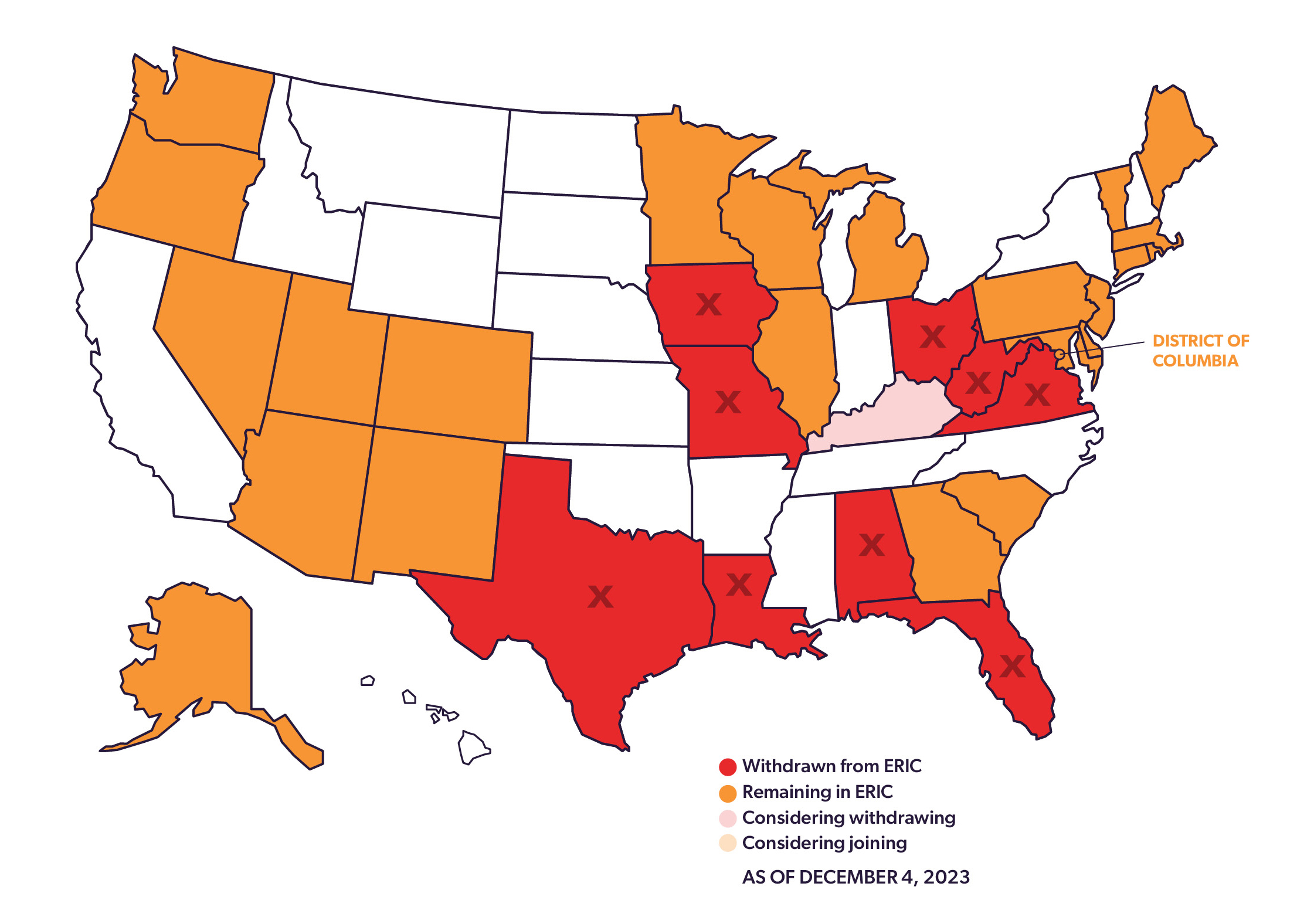

B. Continued Withdrawals from ERIC

In our June 2023 Report, we discussed the disinformation campaign targeting ERIC, a membership organization that helps state election officials maintain accurate voter rolls. At the time of our June Report, despite widespread bipartisan concern about the implications of withdrawing, eight states had withdrawn their membership39A Democracy Crisis in the Making Report: 2024 Election Threats Emerging, supra n. 1, at 23., bringing the total number of state members to 25 as well as the District of Columbia40“About ERIC,” ERIC, accessed Nov. 17, 2023, https://ericstates.org/about/.. In addition, two states (Alaska and Texas) were considering withdrawing, while California was considering joining41A Democracy Crisis in the Making Report: 2024 Election Threats Emerging, supra n. 1, at 23.. Since June, the California legislation stalled42A.B. 1206, 2023 Leg., Reg. Sess. (Calif. 2023). and Alaska’s Division of Elections confirmed its continued membership43James Brooks, “Some GOP states depart, but Alaska will stay with voter fraud prevention network ERIC,” Alaska Public Media, June 8, 2023, https://alaskapublic.org/2023/06/08/some-gop-states-depart-but-alaska-will-stay-with-voter-fraud-prevention-network-eric/.. Texas, however, passed legislation requiring the state’s withdrawal from ERIC, further perpetuating the worrisome cycle that leaves both member and non-member states with fewer options for cross-checking state voter rolls44Natalia Contreras, “Texas begins withdrawal from multistate partnership to clean voter rolls,” The Texas Tribune, July 20, 2023, https://www.texastribune.org/2023/07/20/texas-republican-voter-roll-eric/..

Departing states have cobbled together piecemeal solutions that do not replace ERIC’s functionality. For example, since leaving ERIC, Virginia, Ohio, and West Virginia have entered into bilateral agreements with each other to share certain voter information45Miles Parks, “Republican states swore off a voting tool. Now they’re scrambling to recreate it,” NPR, Oct. 20, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/10/20/1207142433/eric-investigation-follow-up-voter-data-election-integrity.. Virginia also entered into bilateral agreements with Tennessee, Georgia, and South Carolina46Ben Pavior, “Virginia announces new, post-ERIC voter data agreements,” VPM, Sept. 20, 2023, https://www.vpm.org/news/2023-09-20/eric-virginia-voter-registration-data-safety-security-new.. Ohio has also entered into an additional bilateral agreement with Florida47Parks, supra n. 45.. Separately, Alabama’s Secretary of State announced the creation of the Alabama Voter Integrity Database (AVID), one prong of which consists of agreements to exchange voter roll data with Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Mississippi48Patrick Darrington, “Alabama secretary of state unveils new voter roll database,” Arizona Political Reporter, Sept. 19, 2023, https://www.alreporter.com/2023/09/19/alabama-secretary-of-state-unveils-new-voter-roll-database/.. Common throughout these agreements, however, is a failure to share DMV data49Parks, supra n. 45.. Without the inclusion of the unique driver’s license identifiers, some elections officials say these new agreements “look very similar to a now-defunct program known as Kansas Crosscheck,” which also “attempted to compare state voting lists in order to clean voter rolls and find fraud but ran into trouble because of false positives and security concerns.”50Ibid.

Texas’s new law requires the state to develop or find a private sector alternative to ERIC that does not cost more than $100,00051Contreras, supra n. 44.. While no decision has been announced to date, obtained email correspondence reveals one program under consideration is Eagle AI52Documented, Eagle AI Introduced to SOSs That Left ERIC, and is “Under Consideration to Replace ERIC in Texas,” Aug. 17, 2023, https://documented.net/media/georgia-state-board-of-elections-email-showing-eagle-ai-under-consideration-to-replace-eric-in-texas.. Eagle AI is a database that purports “to compare voter rolls with data sources such as business records, property tax data, and mail forwarding and address data from the U.S. Postal Service” and “flags certain voter registrations for review, such as registrations tied to commercial addresses or those in which mail forwarding suggests an individual has moved.”53Jane Timm, “Inside the right’s effort to build a voter fraud hunting tool,” NBC News, Aug. 17, 2023, “https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2024-election/conservatives-voter-fraud-hunting-tool-eagleai-cleta-mitchell-rcna97327. However, the Eagle AI system is untested, and its accuracy and efficacy remain in question. Georgia Elections Director Blake Evans criticized it as offering “zero additional value to Georgia’s existing list maintenance procedures.”54Mark Niesse, “Georgia company pursues multistate voter registration cancellations,” The Atlanta Journal Constitution, Aug. 14, 2023, https://www.ajc.com/politics/georgia-company-eagleai-pitches-private-voter-cancellation-software/TBUCPK5GWZCKBDOJPZQPANOXCY/. Notably, Eagle AI is marketed in part by the Election Integrity Network55Timm, supra n. 53., founded by election denier Cleta Mitchell, an attorney at the center of Trump’s legal efforts to overturn the 2020 election who acted as a “central hub for stolen election narratives.”56Miles Parks, “How the far right tore apart one of the best tools to fight voter fraud,” NPR, June 6, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/06/04/1171159008/eric-investigation-voter-data-election-integrity. As such, states that have withdrawn from ERIC are still in search of reliable tools to ensure the integrity and accuracy of their voter rolls.

C. Burgeoning 2024 Challenges for Election Officials

Election officials around the country continue to face major challenges to successfully administering elections. We have previously discussed how election worker shortages, cyber security concerns, lack of sufficient financial resources, harassment, and misinformation have combined to make election officials’ jobs more difficult, leading many to consider leaving their posts57A Democracy Crisis in the Making Report: 2024 Election Threats Emerging, supra n. 1, at 25.. All these threats persist, with new ones on the horizon.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is top of mind for many, including in the election world. The public launch of generative AI platforms such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT58“Introducing ChatGPT,” OpenAI Blog, Nov. 30, 2022, https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt. alongside the release of open models such as Meta’s Llama 259“Introducing Llama 2,” Meta, accessed Nov. 14, 2023, https://ai.meta.com/llama/. means that today, it is easier than ever for any user to produce high-quality synthetic content across format categories (video, image, audio, and text, including software code)60 Nicole Schneidman and Christian Johnson, How generative AI could make existing election threats even worse (Protect Democracy, Nov. 3, 2023), https://protectdemocracy.org/work/generative-ai-could-make-existing-election-threats-even-worse/.. Synthetic or manipulated content can be used to accelerate and amplify existing threats to election security, including content undermining trust in election outcomes and targeting election officials. For example, generative AI could be employed to produce convincing audio deepfakes of election officials’ voices for disinformation campaigns. Such applications of synthetic content raise concerns regarding the volume and persuasive effect that false information may have in the public discourse in the 2024 cycle61 Lawrence Norden and Gowri Ramachandran, Artificial Intelligence and Election Security, (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, Oct. 5, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/artificial-intelligence-and-election-security?fbclid=PAAaZV5tvi1EAKwqQIgoUm_9WOSrVMJYwYBMCvocmaTys3NOhI_nZtZPvD4qY_aem_Afgjw3t9jbLQFVIoFItOY-wBbPUmEi6Lj-45F7FBuHQ85Z06fK60UJy4vj98NBn_vzrfaLN6GhxITfNSqt6D4G-U; Christina Cassidy, “Misleading AI-generated content a top concern among state election officials for 2024,” PBS, July 15, 2023, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/misleading-ai-generated-content-a-top-concern-among-state-election-officials-for-2024.. Experts have ideas about how to mitigate these effects, which involve both old and new strategies for combating election interference, but it will take time and resources for states to develop solutions62Norden and Ramachandran, supra n. 61..

Our previous reports have also highlighted the election administration risks posed by the departures of seasoned local election officials, whose experience, expertise, and commitment are the bedrock of our free and fair elections. As discussed above, Texas has seen troubling turnover and it is not an outlier. This fall, Issue One published research documenting the scope and the costs of losing experienced election officials63Adrien Van Voorhis et al., The High Cost of High Turnover (Issue One, Sept. 26, 2023), https://issueone.org/articles/the-high-cost-of-high-turnover/.. Their report, which studied the impact in the western states, reveals that tens of millions of voters live in localities where the chief election official has changed since the 2020 election64Ibid.. Many departed because of disinformation and the harassment and threats they faced from election deniers65Ibid.. The loss of experienced officials increases the potential for errors in election administration that, even if they are minor or reparable, can become fodder for election conspiracy theories66Ibid.. Critical to safeguarding nonpartisan election administration is sufficient funding for election offices, rapid response to changing technologies, and safeguards and support for election officials and workers.

Spotlight: Wisconsin

In Wisconsin, election deniers in the statehouse continue to rely on disinformation about the 2020 election in their efforts to harass and remove the state’s nonpartisan top elections official, Meagan Wolfe. While these efforts have so far failed, they illustrate the ongoing damage that election denialism can inflict. Wolfe has served as Administrator to the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission (WEC) since 2018, where she works at their direction and with local election officials to administer the state’s free and fair elections67“Members and Appointees,” Wisconsin Elections Commission, accessed Nov. 14, 2023, https://elections.wi.gov/about-wec/members-and-administrator.. She is a nationally respected figure who sits on numerous state and national boards related to election administration68“Biography of Meagan Wolfe,” Wisconsin Elections Commission, July 6, 2023, https://elections.wi.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/2021-07/Meagan%2520Wolfe%2520bio%25207-2021.pdf., and WEC has won multiple awards under her leadership69“NASED Presents the 2023 Innovators Award to Wisconsin,” National Association of State Election Directors, July 27, 2023, https://www.nased.org/news/2023innovatorsaward..

Some Wisconsin state senators, based on groundless 2020 election conspiracies, are determined in their attempts to remove Wolfe from her post70Harm Verhuizen, “Election deniers rail at Wisconsin Senate hearing over firing top state elections official,” PBS, Aug. 30, 2023, https://pbswisconsin.org/news-item/election-deniers-rail-at-wisconsin-senate-hearing-over-firing-top-state-elections-official/.. In September, the Senate took an unwarranted and improper vote to fire Wolfe, citing a lack of faith among voters71Molly Beck, “Senate Republicans fire elections chief, setting the stage for a legal fight heading into the 2024 elections,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Sept. 14, 2023, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/politics/2023/09/14/wisconsin-senate-voting-today-to-fire-elections-chief-meagan-wolfe/70843196007/. and then a few weeks later, introduced impeachment articles against Wolfe, again relying on these falsehoods72Tyle Katzenberger, “PolitiFact: Impeachment articles against Meagan Wolfe riddled with false and misleading claims,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Oct. 4, 2023, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/politics/2023/10/04/fact-check-meagan-wolfe-impeachment-articles-contain-false-claims/70929834007/.. Despite these theatrics, Wolfe remains on the job as the Senate’s vote was procedurally invalid73Molly Beck, “Elections chief Meagan Wolfe calls her position ‘untenable’ in commission’s dispute with senators,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Aug. 17, 2023, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/politics/2023/08/17/meagan-wolfe-calls-her-situation-untenable-in-dispute-with-senate/70610072007/; Ken Kosirowski, “Meagan Wolfe, Mike Huebsch, La Crosse clerks join panel on Wisconsin election process,” News8000, Oct. 23, 2023, https://www.news8000.com/news/meagan-wolfe-mike-huebsch-la-crosse-clerks-join-panel-on-wisconsin-election-process/article_adc0443c-73b2-11ee-abd6-cb5e28e31547.html.. When the Senate purported to fire her anyway, Wisconsin’s Attorney General sued to prevent further legislative action and confirm her status74Beck, supra n. 71.. In a filing from that case, legislative leaders admitted their action was “symbolic” and that she remains the Administrator75Jessie Opoien, “Robin Vos backs away from lawsuit over attempts to oust elections chief Meagan Wolfe,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Oct. 17, 2023, https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/politics/2023/10/17/robin-vos-backs-away-from-lawsuit-over-attempts-to-oust-meagan-wolfe/71218167007/.. Some legislative leaders are beginning to call the impeachment threats a “distraction.”76“Krug, Snodgrass call push to impeach Wolfe ‘a distraction’,” WisPolitics, Oct. 27, 2023, https://www.wispolitics.com/2023/krug-snodgrass-call-push-to-impeach-wolfe-a-distraction/. Wolfe continues to serve WEC in helping administer Wisconsin’s elections and has confirmed she would not be stepping down77 Beck, supra n. 73; “Wolfe on ‘UpFront’ vows to continue serving as elections administrator amid court battle,” WisPolitics, Sept. 18, 2023, https://www.wispolitics.com/2023/wolfe-on-upfront-vows-to-continue-serving-as-elections-administrator-amid-court-battle..

The attempt to remove Wolfe is indicative of election deniers’ willingness to concoct authorities and procedures to harass and threaten election officials who faithfully follow the law.

D. Efforts to Align with Federal Electoral Count Reform Act

The Joint Session of Congress on January 6, 2021, demonstrated how former President Trump and his allies tried to undermine the provisions of the federal Electoral Count Act (ECA) to foment disinformation and overturn the will of the voters. While there was no factual basis for Trump and his allies’ efforts to override the election results, Congress — on a bipartisan basis — passed the Electoral Count Reform Act (ECRA) in 2022 to update the statutory framework for states to certify their presidential electors, submit their electors to Congress, and have Congress tally their votes at the Joint Session783 USC § 5 (2022)..

While the window is fast approaching, states do have time to review and, if necessary, update their laws and procedures for certifying their election results and selecting and submitting their presidential electors to conform with these updated federal rules and deadlines79National Taskforce on Election Crises, Lessons from the 2022 General Election: How to Prevent Election Crises, and Emerging Issues for 2023, 2024, and Beyond, (Feb. 2023), https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5e70e52c7c72720ed714313f/t/63ebd7de17df7c1ecaf31726/1676400608352/2022+NTFEC+Post+Election+Report.pdf.. For example, the ECA previously outlined a “safe harbor” deadline for states to select their presidential electors. The revised law sets a new, firm deadline of six days before the electors meet to cast their votes (which will be December 11, 2024, for the next cycle). Some states, including Colorado, Nevada, and South Carolina, have already adjusted their laws to align with the ECRA, while others are still in the process or have not yet begun the process80S.B. 276, 74th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (Co. 2023); A.B. 192, 82nd Leg., Reg. Sess.(Nev. 2023); S.B. 405, 125th Gen. Assemb., Reg. Sess. (S.C. 2023).. Michigan closed its legislative session by passing S.B. 590 and S.B. 591, which sets forth the procedures and jurisdictions for contesting post-certification election results, and S.B. 529, which makes conforming changes to Michigan’s presidential electors procedures. These measures were signed into law by the governor.

Updating state law as soon as possible to maximize alignment will help to prevent bad-faith actors from exploiting potential gaps or discrepancies in the state certification process and procedures for selecting the state’s presidential electors and help ensure that the will of the voters is respected and accepted.

ConclusionConclusion

In a matter of weeks, voting will begin in the first nominating contests of the 2024 presidential election. Soon after that, primaries will begin for state elections. As we have documented, voting, canvassing, and certification in 2024 will take place under a patchwork of new state laws. As they prepare for a new election year, election administrators across the country face uncertainty, cumbersome new requirements, insufficiently resourced offices, and the prospect of greater partisan interference, all within an environment of conspiracy-fueled mistrust and harassment.

For three years, we have warned of a democracy crisis in the making as states have taken up bills, and in some places enacted laws, that would increase the likelihood of election subversion. While states have mostly set in place their election rules of the road for 2024, the candidates that will appear on the ballot have yet to be decided and their commitment to nonpartisan election administration will factor into the risk of election subversion. Though we cannot predict which policy may have an outsized impact on election administration, many of these laws introduce opportunities for confusion, disinformation, and system breakdowns in ways that could subvert the will of the voters in the 2024 election cycle.

Note on Methodology

Each year, state legislators introduce thousands of bills related to elections. One organization, Voting Rights Lab, currently tracks nearly 2,000 election-related bills under consideration by state legislatures this year. To create this Report, we relied on the Voting Rights Lab tracker81Voting Rights Lab, State Voting Rights Tracker (accessed Nov. 15, 2023), https://tracker.votingrightslab.org/. and supplemented it with other legislative proposals that we discovered via independent research. We included legislation introduced between January 1 and November 15, 2023. The States United Democracy Center, Protect Democracy, and Law Forward worked together to analyze each proposal to determine whether it would — if adopted — materially increase the risk of election subversion, and to filter out those that we concluded did not meet that criterion.

Latest UpdatesLatest Updates

Year-End Report Details State Legislatures’ Election Subversion Playbook; Examines Laws That Increase Risk of 2024 Election Crisis Year-End Report Details State Legislatures’ Election Subversion Playbook; Examines Laws That Increase Risk of 2024 Election Crisis

Previous Reports

Protect Democracy, along with our partners at States United Democracy Center and Law Forward, issued our initial report in April 2021, less than four months after the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, itself a violent attempt to subvert the voters’ choice. Since then we’ve continued to track the introduction and passage of state election subversion legislation, updating the report in June and December of 2021, and adding a second volume to the report in May 2022.

June 2023

In the two years since our first Report, the danger of election subversion has drawn wider attention. During the 2022 midterm elections, the future of nonpartisan election administration was a campaign issue. Exit polling showed that “democracy” was a top concern for voters. That election came and went without major crises, and the accurate results were ultimately certified on time and in accordance with the law.

December 2022

Across the country, state legislators are proposing and passing bills that would increase the risk of election subversion by giving partisan state legislators greater control over elections and hamstringing experienced state and local election administrators who have traditionally run our elections. These bills would increase the risk of election subversion; that is, of the outcome of an election being contrary to the will of the people.

August 2022

In the 21 months since the 2020 election, we have seen a breakdown in the longstanding consensus that election administration belongs in the hands of professional, dispassionate experts, and that naked political interference in vote counting is anathema to a functioning democracy. Over the course of 2021 and into 2022, state legislatures have embarked on a sweeping campaign to propose, consider, and, in some cases, enact measures that increase the risk of election subversion — that is, the risk that an election’s declared outcome does not reflect the choice of the voters.

May 2022

As of April 8, 2022, legislatures in 33 states are considering at least 229 bills that seek to undermine nonpartisan election administration — 175 introduced in this calendar year alone & 54 that rolled over from last calendar year. A total of 50 bills have been enacted, 32 last year & 18 thus far this year.

MAY 2022 REPORT

December 2021

As 2021 comes to a close, 262 bills have been introduced in 41 states — an increase of more than 100 bills since we began monitoring this trend in April — with 32 becoming law across 17 states.

June 2021

As of early June, there have been at least 216 bills introduced in 41 states that would interfere with election administration.

April 2021

As of April 2021, there were at least 148 bills introduced in 36 states that would interfere with election administration. The Report analyzes more than 50 of the worst bills across the country and finds an alarming pattern in what appears to be a clear reaction to the 2020 election.

Related Content

Join Us.

Building a stronger, more resilient democracy is possible, but we can’t do it alone. Become part of the fight today.

Donate

Sign Up for Updates Sign Up for Updates

Explore Careers Explore Careers

How to Protect Democracy How to Protect Democracy